|

The

Bondage of Debt: A Photo Essay

By

Shilpi Gupta

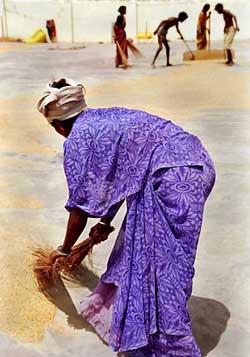

The pounding

sun blisters bare dark skin, scorches the ground, and even boils

water—although it is still only spring in Chennai. Its relentless

glare already makes eyes sting, and summer is yet to come.

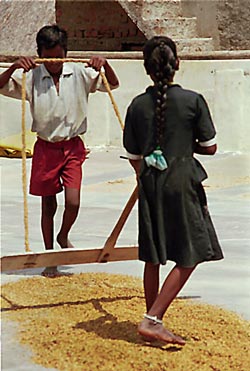

Sathya, 11, and Manakandan, 12, must toil in the heat of tropical

Tamil Nadu, India, moving across the scalding pavement of "nerkalams,"

or rice drying units, barefoot to help their family prepare rice

for local processing mills. But the ground, layered with the sizzling

grains, no longer fazes them as their feet have already been singed

with calluses.

They are two amongst the thousands of children who slave in Chennai’s

nerkalams from dawn until dusk instead of attending school. Their

parents, bonded laborers, depend on their labor to help pay the

debt incurred to loan sharks.

Debt bondage—when a loan requires a person, family and often

heirs to work for another—has been defined by the United Nations

as a

form of modern

day slavery, a practice internationally outlawed. The Indian central

government has also adamantly outlawed debt servitude, enacting

countless laws and policies to eliminate its existence. But with

the power relegated to the state level, such laws are rarely enforced.

"Slavery-like practices may be clandestine," according

to the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human

Rights’ Fact Sheet on Contemporary Forms of Slavery. "The

problem is compounded by the fact that the victims of slavery-like

abuses are generally from the poorest and most vulnerable social

groups. Fear and the need to survive do not encourage them to speak

out."

Sathya and Manakandan’s parents were not always indebted in

servitude. Vinayagam and Chinnapapa only moved to the Red Hills

on the outskirts of Chennai when, after a poor monsoon season, their

farm in rural Tamil Nadu failed to yield adequate harvests, causing

them to fall into debt and sell their small landholdings. At the

time, Sathya and Manakandan, in the second and third grades, respectively,

excelled at their studies. But during the rainy season, in order

to make ends meet, Vinayagam and Chinnapapa were forced to borrow

money, thus ending their family’s freedom.

The conditions of the loan, which requires the family to work at

the loan shark’s rice mill, offer little hope of release from

the burden of their debt, explained George Heston, a social service

worker with the Chennai based NGO, Jeeva Jyothi. Heston says the

government denies the practice’s continued existence.

Chinnapapa explained through a translator that it usually takes

her family three days to finish 27 bags of rice, working from 4

a.m. to 6 p.m. First, the unprocessed rice soaks in water boiled

under the sun. Vinayagam and Manakandan immerse themselves in the

water to separate the rice with men from three other families living

at the mill. The family then spreads the grains over its allocated

share of space, half the size of a tennis court. As the rice dries,

they sift it thoroughly—both with a rake-like contraption and

by walking across it barefoot, combing through the grains with their

toes—and brush it into neat lines with a straw broom. Finally,

they gather the rice in big piles under burlap sacks to dry further

in the heat of the sun. Then, they repeat the process.

For each bag, the family makes 32 Indian rupees, about 80 cents.

Sixty percent of their income pays the debt, said Chinnapapa. The

lender takes the other 40 percent for the family’s room and

board. Meanwhile, the loan also accrues interest, causing them to

accumulate more debt—creating an endless cycle of bonded servitude.

The children sporadically attended Jeeva Jyothi’s tutorial

courses, and the organization eventually convinced their parents

to send them to school again. In the 1999 edition of its publication,

"A Child’s Voice," Sathya described her excitement

over her father’s permission. "I hope he will not change

his mind after my admission. I will be the happiest person in the

world if I go to school," she wrote.

But her brother, Manakandan, was thought to have more potential

for schooling, and without his hands, Sathya’s labor was indispensable.

Her father was forced to recant.

Families in the Red Hills are not alone in their plight. The United

Nations’ Working Group on Contemporary Forms of Slavery, acknowledging

the difficulty in obtaining reliable data, reported that organizations’

estimates suggest as many as 44 to 100 million persons live in debt

bondage in India alone.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights maintains, "No one shall

be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall

be prohibited in all their forms."

Yet this year the International Labor Organization, a subdivision

of the United Nations, documented the progression of bonded labor

in its annual report, titled "Stopping Forced Labor."

In 1978-79, NGOs estimated over 2.6 million bonded laborers in 10

Indian states surveyed. In 1995, the Supreme Court received a report

by the Commission on Bonded Labor in Tamil Nadu estimating 1.25

million bonded laborers in the state of Tamil Nadu alone. Additionally,

some organizations estimated 65 million children are living in a

similar condition.

In a later edition of "A Child’s Voice," Sathya described

her love of drawing, studying, playing and singing. "But I

don’t have time for that," she wrote. "I have to

be with my father and mother to contribute my share of income."

|