|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Travel

writing unplugged:

Notes from a travel writer on foreign tourism in China

By Mielikki Org

The police officer, seated in a rotating chair, propped his feet up on the desk. His left hand held a cigarette, which he puffed on as he read out loud from the small, paperback handbook in his right hand.

Looking over to where I was seated on a wood bench, he repeated the same sentence for what must have been the twentieth time. "Foreigners staying illegally in China must pay a fee of 500 yuan per day," he said, in carefully-enunciated English.

|

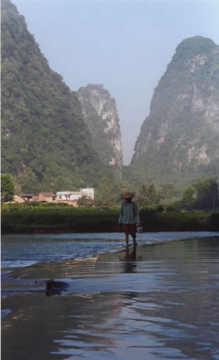

| Yangshuo scenery, in front of the Riverside Retreat |

After three hours of apology, including a written self-criticism earlier that morning, I had been unsuccessful in convincing the recalcitrant officer of my innocence. He was still intent on making me pay the maximum fee, about $362. Officer Bing was notorious among local Yangshuo café owners for trying to wrangle money from confused tourists like myself, who had accidentally misread their visa validations.

He closed the book and put it on the table, then focused his attention on me again.

"Normally I would charge you 3,000 yuan for not renewing your visa, and for staying illegally in the countryside," he said. "But since your mother is Chinese, I'll charge you 2,500 yuan."

"Staying illegally in the countryside" in this case meant being "caught" in a countryside residence seven miles outside of town. For the past month, the refurbished farmhouse-turned-guesthouse known as the "Riverside Retreat" had been my home, while I toiled to finish a manuscript for the travel guide Fodor's. One of Bing's primary responsibilities as a police officer was to keep foreigners properly corralled among the bars, trinket shops, and Western cafés that dominated the center of this rural but increasingly tourist-mobbed town in southern China.

After two hours, I bargained Bing down to about 500 yuan, or $62. It was more than his monthly salary. The owner of the guesthouse was fined 150 yuan—not so much for her "wrongdoing," she believed, as for Bing's "jealousy" of her success. I soon learned from other locals that Bing's behavior wasn't out of character. Even offering me a discount for my partial "Chinese-ness" was in line with the practice of state-run hotels all over China, which required "non-Chinese" foreigners to pay full price. Bing was just taking hints from government policy. And with so many tourists in Yangshuo throwing money into expensive Western dishes, souvenirs, and email cafés—at twice the prices charged in other parts of China—he probably felt justified in taking money from "rich" foreigners. In a small way, he may even have considered himself an entrepreneur.

Espressos for the masses

|

| The guidebook updated in 2001 by the author. |

Traveling to Yangshuo as a travel writer in June 1999, and returning two years later as a travel writer for the Australian guidebook Lonely Planet, allowed me to witness some of the effects of tourism on China's economy, culture, politics, and society. Over the past ten years, this rural, farming town an hour's bus ride east of the tourist destination of Guilin has been transformed into a bizarre amalgam of foreigners and local residents, where hordes of backpackers sporting Teva sandals and skimpy tank tops mingle with farmers toting crates of cabbage.

Yangshuo sprouted two Western-style cafes offering espressos and pizza in 1989. Backpackers found it a cheaper alternative to Guilin with the same craggy limestone peaks and river vistas. The small town had a more authentic, "off-the-beaten track" feel.

By 1999, Yangshuo's two original cafes had been upstaged by an entire street of shops, cafes, and hostels, now called "West Street." New establishments with names like "Minnie Mao's" and "Planet Yangshuo" seemed to pop up overnight.

On West street, everyone speaks English. Outdoor menus offer French bifteck and spaghetti bolognaise. Bars play pirated CDs featuring the latest hits of N'Sync or Eminem, and every café has VCDs of movies like The Buena Vista Social Club and Meet the Parents. Amidst the email cafes and mountain bike rental stands, overeager tour guides prowl the streets like bloodhounds, while Chinese students intern for the summer as waiters and waitresses in the cafes, hoping to practice their English and learn more about the tourist industry.

Immediately outside of West Street, merchants still sell live chickens, street vendors hawk noodles and vegetables, farmers haul carts of yellow melons called hamigua, and bicycles stream by with their riders precariously balancing umbrellas to ward off onslaughts of tropical rain or sun.

During my stay in 1999, five new hostels and restaurants were under construction. When I returned to Yangshuo in 2001, at least fifteen new tourist sites had opened. One street, which used to be lined with hair salons and shops selling mechanical equipment, had been torn down to make room for a hotel. Some cafes had changed ownership.

|

| A Yangshuo farmer crossing the river just outside of the Riverside Retreat in the countryside. |

Foreigners cringed when accosted by aggressive, haranguing merchants and motorcycle drivers screaming "Hello! Hello!" Such foreigner-pursuing protocol had been nonexistent in Yangshuo two years ago.

Littering, smoking bamboo raft operators had taken over the riverside guesthouse where I found peaceful refuge in 1999. About thirty, ten-foot long boats cluttered the "natural swimming pool" where guests and local farmer's children used to swim. The owners, who slept on the rafts overnight, harassed me constantly.

The guesthouse owners had been fighting with the raft owners since they arrived last year. "They're doing business," said the countryside owner's niece, a 28-year old woman named Linda. "That's how they get their money. They say they don't have any other choice."

Foreign tourism in China has increased by over 50% over the past ten years, affecting more than the entrepreneurs. In Yangshuo and other tourist destinations--from Hunan to Hainan Island--I noticed the behavior of bus and taxi drivers, restaurant owners, hotel service people, residents, students, and other people trying to profit from tourist revenue streams. But usually they are driven by need, by convenience. And by profit. Sometimes they seek out tourists to learn and interact more with the West.

For the past ten years, capitals like Chengdu and Guangzhou have been regularly razing historic temples to make room for shopping centers and international-style hotels and business centers. The number of agencies appointed by the government to handle tourists has doubled within the last ten years.

As a travel writer, I often struggle with the knowledge that, by referring foreigners to places such as Yangshuo, I am encouraging rural towns to adopt a new and potent version of Western capitalism. China's entry into the World Trade Organization is sure accelerate that trend, as Chinese businesses rush to compete with foreign companies and profit from increasing tourism. The number of businesses catering to tourists is sure to increase, along with hotel prices. Those who see upward salary shifts will not be taxi drivers and hotel clerks but the state, private, and international entrepreneurs who stand to gain the most from expanded tourism.

A Yangshuo café owner

Lu Hua Ping, 28, likes to go by the English name of William. In 1999 he was the proud owner of two popular, Western-style cafes on Yangshuo's West Street.

This year, William had only one café. He'd been forced to sell his first cafe to the state, which planned to use the land for a hotel. He'd left the other one after getting into disputes with a partner and opened the bigger and better "7th Heaven" down the street.

While he talks to me at one of the wood tables in front of the café, William scans the traffic of passing backpackers. He tries to make polite conversation, stops frequently to call out greetings to tourists he's met already and newcomers to the café.

|

| Ms. Lu, the author, and Yangshuo residents at her son William's "7th Heaven Café". |

Williams charismatic personality, good English, and willingness to drink beer with new friends make him popular among tourists, who often seek his help in booking train and bus tickets. But whenever he gets a break, William looks worried and exhausted.

"I have to go to Guiyang to be a tour guide for two French women tomorrow," he groans, as he picks at the bowl of rice with greens and pork chunks his mother has just put in front of him. William's mother helps the three cooks in the kitchen at the back of the café. His father, a farmer, looks after their house in the countryside.

William has been running the business by himself for a year. In 1998, he started his first café shortly after graduating from the Guilin Tourism University where he learned English. He is currently learning French from a tourist names Jacques.

"Sometimes I worry that Hua Ping is doing too much," his mother tells me, as we eat with the other cooks in the kitchen. Ms. Lu doesn't speak English and seems much more comfortable in the small, windowless kitchen than at the wood tables outside.

"He's been so successful, and his father and I are really happy. But I wonder how long he'll be doing this. I hope he'll meet a nice girl and get married someday. I hope he meets a foreign girl, although a nice Chinese girl would be ok too," she says.

Ms. Lu's comment voices a wistful "longing for escape" sentiment that I heard often from hotel clerks, taxis, and restaurant owners plying the tourist trade.

A farmer's daughter in Fujian

|

| Tourists on bamboo raft rides in Wuyishan (Fujian province). |

Like most Chinese students learning English, the hotel clerk in Wuyishan was hesitant to talk to me at first.

Wuyishan is a small town in the mountains of northern Fujian. In the past Chinese tourists were the majority. But Wuyishan is starting to see more and more foreign tourists, as evidenced by the recent construction of a four-star hotel.

At first I met a lot of shy smiles, and some hovering outside my hotel door. At about 10 pm one night, after the boss had gone to sleep, Liu Li Ping finally came to talk to me. What started as an English practice session with a hotel clerk turned into a three-hour confession from a 16-year-old girl facing some tough problems in the countryside.

"I'm not supposed to be working here," she said, speaking low so that the other women working at the hotel wouldn't hear. "I'm working as a child laborer. I'm only 16. The other girls don't know," Liu said.

"My aunt helped me get the job here because she knows I need money," Liu said. "I had to drop out of school. My teacher tried to convince me not to, and my father says I should go to school. But how can I? Who else will pay for food and clothing for me and my little brother?"

Liu says that her favorite teacher in school, who teaches English, has tried to convince her to stay in school. But, because of the scope of her problems, all he can lend is a sympathetic ear. " He wants to help me, but he tells me, 'there are a lot of other people in the same situation as you, how can I help you all?'

Liu's mother, a native of Sichuan, left the family when her daughter was only seven years and has not been heard from since. Liu says her father, a farmer, earns about 400 yuan a month. But he gambles and drinks it away, so she works at the hotel earning 200 yuan a month.

Liu hopes that she will be able to study English on her own, but complains that she never has any time because of her work.

"There's so much stress. I cry every night. Sometimes I think I won't be able to take it anymore. I even think of suicide." Her words are a rush of hushed, desperate tones.

Liu's talk of suicide is not uncommon among women facing economic and social crises in the countryside, and China now faces the highest female suicide rate in the world.

For Liu, English presents a passport out of desperate problems when government and society offer no solutions.

Although she has only studied a short time, her English is excellent. "My teacher says I'm the best in the class. Can you tell me, what's the best way to study English?"

Jiangxi bus drivers at a Buddhist temple

In the midst of a twelve-hour bus ride between Jingangshan mountain, a popular Chinese tourist site in southern Jiangxi, and Hengyang, a city in southern Hunan province, I befriended three bus drivers.

One, a man in his 30s, drove the bus. His wife, also in her 30s, collected the tickets. Their friend, a young, 26-year-old woman, alternated shifts with the wife. They were all from Jiangxi.

When I told them that I was going to visit Hengshan, a sacred Buddhist mountain close to Hengyang, the following day, they decided to go with me. All three were Buddhists who had never been to the temple, but they thought it would be fun to become tourists for a day.

|

| Bus drivers from Jiangxi province with author at Nanyue Temple in Hengshan (Hunan province). |

We took a minibus to Hengshan the next morning. The husband started chatting with a man who ran a restaurant and incense shop there, and we followed him to his store, only to be pushed into buying $24 worth of incense and firecrackers to be offered at the temple.

"What are we supposed to do with these?" the wife said, after handing the salesman 48 yuan. Each of us had a plastic bag full of firecrackers and baton-sized incense sticks. I didn't realize that the wife had negotiated purchases for all of us.

Burning incense at temples is a common Chinese ritual, and incense merchants—sometimes very aggressive ones—regularly accost Chinese and foreigners tourists.

"Let's just watch for awhile, to see how other people do it," the husband said once we arrived at the front of the temple.

Five people tossed their entire bags into the large, vaulted furnace, then retreated as the firecrackers started exploding, so we disposed of our bags similarly. After making the rounds to the various Buddhist to pray, my three friends decided that being a tourist had limited appeal.

"This isn't any fun," the wife said. "My feet hurt," said their friend. Both had worn two-inch high platform shoes for the occasion. The bus driver's wife had also tried to "dress up" by wearing lipstick, an extremely short tennis skirt, and a tight black t-shirt. I still planned to hike up the mountain, so they decided to return to Hengyang.

Later, I met the incense seller, who invited me to eat dinner with his family. We talked about the bus drivers.

"It wasn't any fun for them because they didnt have any money [to see other places on the mountain]," he said. "Maybe they were hoping you would pay."

Tourism 101

The eight students were eager to practice their English but too scared to accost foreigners. They had been invited to intern for the summer at the Riverside Retreat by guesthouse owner Shelley Chen, who taught most of them English at Yangshuo's "tourism school." In return for helping with cleaning, reception, and general duties, the five girls and three boys would get free food and lodging at the guesthouse. Many hoped eventually to land jobs in the Yangshuo tourist industry.

"Don't let them speak Chinese to you," Chen's niece, Linda, advised me. "Make them practice their English."

Linda herself had gone through a similar process when the guesthouse first opened. Aggressive English practice had helped her advance from hotel clerk to assistant manager of a new guesthouse that was being built nearby, called the "Mountain Retreat."

Chen planned to make the Mountain Retreat into a hotel for groups studying English. Programs offered at the guesthouse, Chen said, would promote cultural exchange between Chinese and foreigners while allowing students to practice English.

English has become essential for any young person seeking a future in the Yangshuo tourist industry. Many from Guilin's University of Tourism come to Yangshuo's cafes to intern for the summer, eager for the opportunity to interact with foreigners, while local young people regularly scout the cafés and parks in search of language partners.

Café waiters and waitresses with functional English can become tour guides, like Bill, 26, who worked at William's café in 1999.

"I'm a guide now," he scoffed, when I asked if he was working at William's new café. Like many waiters and waitresses, Bill had grown up in the countryside, where his parents, too were farmers. He said he hoped to open his own café on West Street by the next time I saw him.

Not everyone aspiring tour guide is successful. I encountered many students who decided to return to Guilin, either because their English wasn't improving or because the 12-hour café work shifts, five days a week, were just too difficult.

But others, like Bruce, 18, remained enthusiastic.

"I like talking to foreigners," said Bruce, a Michael Jordan fan who regularly invited me to play basketball. "But English is so difficult. At least there are many foreigners here. We never have opportunities to practice at [Guilin] University."

The future of Yangshuo

With the success of her Riverside Retreat, Chen is negotiating with business planners to build her "Mountain Retreat" at another spot down the river.

|

| Farmer with his buffalo in the Yangshuo countryside. |

For Chen, the eldest of five daughters, mustering the money and nerve to buy the Riverside Retreat's farmhouse in 1998 was a challenge. She spotted the farmhouse while swimming in the river one day, but her earnings as a schoolteacher were meager. Chen was finally able to save up enough money to buy the house and business has been successful since the Riverside Retreat opened in April of 1999.

Two months later, Chen was already negotiating with state tourist boards about building other rural guesthouses without threatening the Yangshuo countryside.

When I visited her in 2001, the Mountain Retreat was almost completed, but I gradually realized the new guesthouse was not just her own initiative.

Chen said she was working with government officials to build the Retreat because she had no choice. The land that the Riverside Retreat stood on belonged to the state. "If I work with them, I may get to keep Riverside Retreat," Chen said.

But she also expressed hope in her ability to influence planners' decisions. "They will listen to me," she said. "They like my ideas. We are all committed to developing the area in a way that preserves the environment. We won't have any big hotels, just small ones. I don't think they want to risk ruining this place," she said.

But in the center of town, changes are already happening too quickly for anyone to interfere. Hotels and cafés catering to foreigners spill beyond West Street into the local districts. Areas clogged with trash and debris are being beautified. And many Chinese tourists now stroll down West Street.

Yangshuo reflects startling changes taking place in every urban center in China. Chinese have adopted Western food--via McDonald's and Starbucks Cafes in larger cities. Platform shoes and miniskirts, see-thru tops, sports clothing, and white wedding dresses have been popular in China for a decade. Hip-hop groups and artists like Madonna and Eminem are well-known to younger Chinese audiences.

Now rural towns are at risk as larger forces shape the middle and upper classes. While William, Chen, and Liu, find new opportunity, people who lack business skills, foreign language, or property ownership rights may be pushed out of the competition. Hotel and café owners like William may be able to ride the current waves of tourism, but hotel clerks like Liu will likely remain locked in service positions.

Increased tourism in China will continue to be a blessing and a curse to a nation that is still developing its own cultural and economic terms towards modernization. Foreign tourists, as both investors and consumers, will certainly be affected by the changes. But one must also remember that increased access by foreigners to the countryside can only be read as a leap in progress, considering that this kind of intercultural and social exchange was almost impossible twenty years ago. And closing the gap between two cultures, even through tourism, can never be a bad thing.

October 31, 2001