|

PRODUCE

by John Coté

Photos by Nirmal Govind

At 4 AM. fumes from propane-powered

forklifts cut the soft aroma of green tomatoes and half-ripe bananas.

Dawn is hours away, but the business day is in full swing at Oakland’s

wholesale produce market, four square blocks of open-faced stores with

sweeping awnings just off Jack London Square.

Lumpers – the colloquial term for workers who unload produce –

dart forklifts between a jumble of trucks, crates and each other, building

a maze of Big Jim Oranges and Pim Fresh Cabbage along the sidewalks and

storefronts. Other lumpers wheel dollies stacked with gnarled ginger,

plump eggplant and vibrant chilies through the cold and onto rigs waiting

to deliver them to customers. The fruits and vegetables arrived from farm

shippers as early as 1 a.m. As the sun rises they’ll be trucked as

far away as Napa County to chain grocery stores, independent markets,

restaurants, caterers and other wholesalers.

A similar scene has unfolded in the neighborhood most mornings for the

last 120 years. Now some of the largest produce merchants say economic

pressures will kill the market – about 15 wholesalers who combined

do about $100 million in annual sales – unless the city helps them

move quickly and collectively.

"We’re drowning," said Albert Del Masso, co-owner of Bay

Cities Produce and president of the Oakland Produce Association, a coalition

of wholesalers founded 9 years ago to lobby the city for help. "If

this produce market fails, Oakland won’t have a produce market."

The market is being pressured from several directions as the city looks

to implement Mayor Jerry Brown’s vision to revitalize Oakland. It

lies in the middle of an area slated for redevelopment under the city’s

Estuary Plan. Adopted by the City Council in June 1999, the Estuary Plan

envisions a tourist-friendly area of eclectic retail stores, charming

restaurants and designated open spaces incorporated with residential lofts

and high-tech businesses. The bulk of Oakland’s waterfront property

– a mix of heavy industry, commercial stores, and registered historic

buildings from Adeline St. to 66th Avenue, and the water to the Nimitz

Freeway – is being rezoned for that purpose. The produce market lies

in a key corridor that links downtown Oakland and Chinatown with the bay-front

Jack London Square, promoted in the Estuary Plan as the "East Bay’s

primary dining and entertainment venue."

The Estuary Plan does not call for the removal of the produce market,

but real estate prices in the area have soared, increasing the incentive

for building owners to bring in tenants who pay higher rents. Oakland

Produce Square, a group of 13 businesspeople that owns the four main buildings

in the market, has put them up for sale and refused to renew long-term

leases. Leases that recently expired are now on a month-to-month basis.

Judy Chu, one of the owners, said the time is right to develop the area,

and her group is keeping its options open. She said it would be a smart

business decision for Oakland Produce Square to sell some or all of its

buildings to developers, or else bring in technology companies, preferably

by constructing high-rises.

"The area is due for development," Chu said. "Really anything

is possible."

But putting in high-rises is not part of the Estuary Plan and would seem

a remote possibility, said Betty Marvin of the city’s Community and

Economic Development Agency. It would require petitioning for an exemption

to the zoning laws currently being hammered out by the City Council, since

none of the proposals allow high-rises. Oakland Produce Square’s

buildings, all built between 1916 and 1917, are also on the Local Register

of Historic Resources. Any significant structural changes would require

an environmental impact report, a lengthy and costly study outlining potential

effects on everything from recreation to air quality to geology that would

then be scrutinized by the city, Marvin said.

The historic buildings have also handcuffed the produce merchants, but

for different reasons. The merchants said they simply don’t have

room to put in loading docks, modern refrigeration units or additional

warehouse space. They said their businesses have reached critical mass,

and they’ve had to turn away potential customers like Ralph’s

Groceries and some restaurant chains because they don’t have the

facilities to fill more large orders. The lack of loading docks also makes

the operation less efficient because workers have to do all the unloading

by forklift or by hand.

"I don’t have enough outlets in the office for computer equipment,"

said Gaile Momono, general manager of Fuji Melon, which has a year and

a half left on its lease. "It’s tough to put money into rewiring

a building you don’t own and don’t know how long you’ll

be there."

The antiquated buildings have prompted produce merchants to talk on and

off for 30 years about moving. But the influx of dot-coms, uncertainty

about leases and desire to expand have added a sense of urgency to discussions

with the city about a new site.

"We need to be out of here, and they need to help us get out,"

Del Masso said. "I need to grow and I’ve got people I can’t

supply." Steve Del Masso, Albert’s son and co-owner of Bay Cities,

estimated the market lost $10 million last year because of customers it

had to turn away.

The merchants say all they want is the city to sell them at a fair price

a parcel of land large enough to transplant the whole market intact

.

Don Ratto, who helped found the Oakland Produce Association lobbying group

and co-owns Leo Cotella Produce, the largest merchant in the market, rents

his store from Chu’s group. He has a month-to-month lease, which

allows him 30 days notice if Oakland Produce Square sells and the new

owner wants him out.

"If they throw us out of here, we’re going to relocate,"

Ratto said. "It’ll take a lot of adjusting, but the market has

to stay together."

Most owners agreed the market needs to be a close group of wholesalers

to be successful. Proximity to other produce merchants gives buyers a

broad selection in one place, and allows the wholesalers to simply go

next door to buy parts of a large order they wouldn’t otherwise be

able to fill. If customers have to drive to multiple sites to fill an

order, they will take their business elsewhere, merchants said.

"Collectively you have a viable market," Albert Del Masso said.

"Separately the selling power will be so low we won’t survive."

The Oakland Produce Association has a site in mind, but they say political

foot-dragging has kept them waiting. They want 18 acres between 7th and

Grand streets, on the former Oakland Army Base. The site would provide

them with space to expand, loading docks to increase turnover and a location

where trucks would have easy highway access but wouldn’t disturb

neighbors at 2 a.m. But securing the land requires complicated negotiations

between the produce merchants, the city and the Army.

Wendy Simon, the produce market project manager at the Community and Economic

Development Agency, acknowledged the city’s pace has been slow, but

said the process is complex.

"Everything moves a lot slower than everybody wants, but we are trying

to push the action," Simon said. "It is the city’s intention

to retain these merchants."

The former base is still owned by the Army, but the particular site the

produce merchants want is owned by the Army Reserve, which negotiates

its own contracts. After initial talks with lawyers representing the produce

merchants, Simon said, the Army Reserve decided to deal only with the

city on the transfer, Simon said. This has added another layer to already

complex negotiations, she said—and the merchants’ group is only

one of many competing now for Oakland officials’ attention.

"Personally, I think the market is important," Simon said. "But

I’ve never heard the mayor mention a new produce terminal."

Produce merchants said their less-than-glamorous image has worked against

them in talks with the city, which the merchants contend is more interested

in attracting high-tech companies. "The city is kissing the buns

of the dot-coms," Albert Del Masso said. "All the high-tech

in the world is not going to do you any good if you can’t get fed."

Fuji Melons’ Gaile Momono said the market is often overlooked because

it operates while most people sleep and involves down-to-earth work. But

it does employ 400 unskilled Oakland laborers and pays them good wages,

Momono said. Figures from the city’s Business Tax Division show merchants

last year generated an estimated $100,000 in sales tax revenue for the

city.

A long-time produce merchant who wished to remain anonymous said the market

also provides an opportunity for workers who couldn’t hold 9-to-5

jobs to be successful.

"People are different here," he said. "In society they

are marginal, out of place. But people survive here. Are these people

going to be able to get jobs if this market closes down? Probably not."

The market has long since closed for the day by the time the trendy Soizic

Bistro-Café begins to hum in the afternoon. Half a block down a

black Volvo sedan crushes bruised green tomatoes that had scattered in

the street sometime during the morning mayhem. The driver parks in front

of a law office next to the shuttered store fronts. Without a glance back

the car’s occupants head for Soizic, making Momono’s words seem

eerily prophetic: "Honestly, for most people, they wouldn’t

know it’s gone."

Home

|

Lumpers

take a coffee break before dawn.

With

space at a premium, all sidewalks are fair game, including those in front

of the neighborhood restaurant, the Oakland Grill.

A

forklift driver pauses before heading back into the unloading fray.

A

lumper runs produce to a waiting truck.

The

modern face of the produce market.

Without

loading docks, forklifts are the backbone fo the produce market.

Activity

at the market peaks well before dawn.

A

worker clears away the remains of a hard morning's work.

A

lumper at Bay Cities Produce loads a delivery truck by hand.

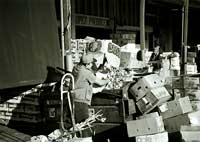

Truck

congestion was not an issue in the 1930s.

(Photo

courtesy of the Oakland Public Library)

|