|

Cop Crisis: Officer

Shortage Has Oakland’s Police Department Looking for More Than Just

a Few Good Men

By

Nerissa Pacio

Photos By Nerissa Pacio

Oakland Police recruiter John

Lois won’t set up his booth at another Silicon Valley job fair. "It’s

just not worth our time," he said.

Unlike the Oakland Police Department, high-tech companies have money to

spare. At any given job fair, recruiters pass out everything from stuffed

animals to CD holders. Nortel Networks gives away plastic sports bottles

and stress relief toys. Cisco hands out cappuccinos and rubber superballs

that light up when bounced. But more appealing than the free stuff is

the cash— cash the Oakland Police Department simply doesn’t

have to offer.

While the dot-coms, Ciscos, and Intels wooed potential employees with

six-figure salaries and stock options at one recent fair, Lois was offering

glossy pamphlets and a potentially dangerous civil service job that maxes

out at a salary of $65,604 a year.

"It’s the same old story," Lois said. "The economy

is very good, and with the explosion of technology in the private sector,

it’s getting harder and harder to recruit."

The Oakland Police Department is facing an officer shortage. Lois said

his department loses about four officers each month and now has only 720

out of the 748 sworn officers Lois wants hired by the end of the year.

Oakland Police Patrol Captain Ralph Lacer said he faces the same problem

other commanders face in the department. He never has enough officers

to patrol every beat in his area, and as a result, beats go under-manned.

"I always have more overtime positions open than officers actually

working," Lacer said about his command area from Lake Merritt to

Berkeley, and Alameda to the Oakland hills.

Oakland is not alone. Departments nationwide are shorthanded, with fewer

people entering the law enforcement profession every year. According to

law enforcement officials, the shortage is considered a crisis that has

caused many officers to work overtime. It has spurred a surge of creativity

in recruiting tactics and intensive studies on how to increase recruitment

and retention.

William F. Naber, president of the national public safety training and

consulting company Naber Technical Enterprises, conducted a six-month

nationwide study of law enforcement agencies’ hiring, recruiting,

and retention techniques. He found that police departments have, on average,

only 40% to 50% of their sworn officer positions filled.

Naber said the officer shortage is a result of the decrease in the number

of applicants combined with the high cost of screening applicants. He

said that, on average, 100 applicants are screened to fill one law enforcement

position, and that screening takes more than a year, costing agencies

between $40,000 to $128,000 per person. During the long screening process,

normal attrition occurs because officers are sick or they retire. While

trying to find just one suitable candidate, more and more positions go

unfilled, forcing more officers to work overtime.

Naber also said many departments do not have enough funds, which come

from city tax money, set aside for recruiting and screening.

Lois said Oakland has increased recruiting efforts in the last three years.

"We’re on a hiring frenzy at this point," he said.

Lois still uses some of the traditional recruiting techniques, like attending

college job fairs. But the officer shortage, which has sharpened in the

last year, has forced him and other recruiters to turn to new tactics.

Just last month the Oakland Police Department and the California Highway

Patrol co-hosted 80 other agencies at the Bay Area’s first law enforcement

job fair.

Six months ago, Lois flew to Louisiana and Texas for potential recruits.

He visited four Louisiana colleges and five big colleges in Texas, including

Texas A&M. He said the department wanted to target large schools that

had criminal justice programs. He also posted ads on the Internet, reaching

a much larger audience, instead of putting ads in the newspaper. He has

even spiffed up his fliers and pamphlets, creating one geared especially

for high school and college students. He said the cadet program aims at

getting to young people before the private sector does.

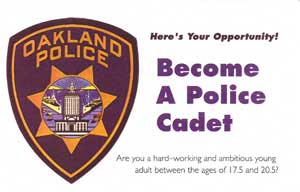

The pamphlet’s cover reads: "Here’s your opportunity! Become

a police cadet. Are you a hard-working and ambitious young adult between

the ages of 17.5 and 20.5?" Inside, the pamphlet includes about two-dozen

pictures of young, smiling recruits and a list of a cadet’s possible

assignments, from fingerprinting and traffic control, to crime analysis

and blight enforcement.

Other departments are trying monetary incentives to boost recruitment.

Contra Costa Sheriff Department recruiter Marcus Morales said his department

offers a $3,000 signing bonus for officers who bring in new recruits.

Lori Lee, a Vallejo Police Sergeant assigned to a yearlong study on recruitment

practices at the Sacramento-based California Commission on Peace Officer

Standards and Training, said some factors contributing to the trend are

unique to the Bay Area. Lee said fewer people are attracted to the police

profession because police salaries are not enough to support a family

and afford Bay Area housing. The soaring prices force officers to find

cheaper homes in outlying areas, creating long commutes for many tired

officers who are already doing overtime.

Lacer said the department has always had many officers working on their

days off. "Without overtime, I’d be in big trouble," he

said.

Many officers welcome the chance to make an extra $500 to $600 dollars

a day in overtime pay, Lacer said, but slots still go unfilled. He said

Oakland Police Chief Richard Word is wary about forcing officers to do

overtime because it "creates animosity, lowers morale, and creates

potential family problems as severe as divorce."

Lacer said the department has discussed with Jerry Brown the need for

increased policing needs to accommodate Brown’s plan to bring 10,000

new residents to downtown Oakland. He said the department plans to hire

200 more officers within the next two years, on top of the 748 they hope

to have in place by next month.

The Oakland Police Department has had an added obstacle to recruiting.

Two years ago, a city mandate required new police officers to live in

a specified zone close to Oakland city limits so that officers would be

nearby in case of an emergency. Lois said that because Oakland is the

only Bay Area police department with this requirement, he has lost many

applicants to other agencies like the Alameda Sheriff’s Department

and nearby police departments.

Officers from those agencies have the freedom to live as far as San Joaquin

County, where homes are significantly cheaper. Lois said he has had applicants

from Modesto, Pittsburg, and Tracy who were very close to signing on.

But as soon as they found out about the residency requirement, he said,

they decided against the Oakland department.

"People just aren’t willing to give up that flexibility and

have someone tell them where to live," Lois said. "We fought

the city on this and lost…But right now it’s an issue that’s

not up for discussion."

With the influx of businesses, which is helping to revitalize Oakland’s

economy, housing prices continue to soar. According to the California

Association of Realtors, the median home price in Oakland rose from $180,000

to $263,000 in the last year, a 46.1% increase. Lois said it seems ironic

that the very forces that are helping to reshape Oakland are contributing

to the officer shortage in the Oakland Police Department.

"As things progress, certain areas, like the police profession, suffer

because of it," Lois said.

Lee said other factors that discourage people from entering the profession

state-wide include the long testing and selection process that takes between

six months and a year, and the repetition of filling out complicated applications

in order to apply to multiple law enforcement agencies. He said the Rodney

King beating and recent police corruption scandals in Los Angeles have

also contributed to the negative image of police officers.

"Back in the day people had a very positive image of police officers,"

Lois said. "Now people think it’s not worth it. It’s too

dangerous. As crime has risen, the job has been looked upon less favorably."

Another factor contributing to the recruiting problem is the competition

between agencies, Lois said, since the California Highway Patrol and local

sheriff and police departments are all vying for candidates from the same

small applicant pool. Lois said many Oakland Police applicants are military

recruits, recent junior college or university graduates of criminal justice

programs, second and third generation police officers, and people who

are switching careers altogether.

Alameda County Sheriff’s Department recruiter John Nolan said that

five years ago between 500 and 600 people would apply to become a sheriff

compared to the maybe 200 who now show up for each of the tests, which

occur four times a year. Nolan said the Oakland Police Department is their

biggest competition.

Although Lois said he won’t go back to the tech fairs where he can’t

compete with the dot-coms that have the "fancy tables, flashing lights,

and paraphernalia giveaways," he hasn’t given up his sales pitch.

Lois said police officers still have better benefits and retirement packages

than many of the start-ups. Added to their salaries, officers get full

medical and dental coverage and incentive pay for those with college degrees.

They can also retire with a large retirement package at age 50. And, he

adds, it’s a stable, community service job.

But Lois realizes his pitch may not be enough. His department can’t

afford a large-scale marketing campaign that he said would cost up to

$50,000, "just a drop in the bucket for a dot-com." But what

he’d really love is just enough money for two more full-time recruiters

in his department and a huge billboard on the side of the freeway. On

it, Lois envisions a big navy and yellow Oakland Police shield and a logo

that reads, "Pride and Commitment: The Oakland Police Wants You."

Home

|

Nor

Cal Job Fair

Nor

Cal Job Fair

|