| J.T.'s Dad

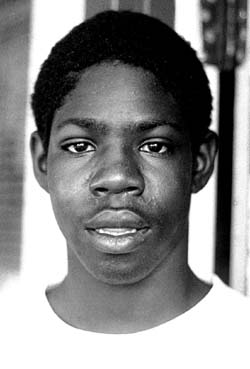

Coleman, 35, has only been out of prison for less than a month and vows that his 15-year-old son Joseph "J.T." Torrence will follow the straight-and-narrow path. "The only difference between me and him is that he's going to do something with his life," says Coleman. "Besides, I told him I would kill him, if he f...d up." But J.T., like his dad, is finding it hard to stay out of trouble. Not long ago he was suspended from the 49ers Academy, a one-year-old middle school for boys with behavioral problems, after already having been expelled from a regular middle school, Belle Haven, for constantly fighting and disturbing the class. "J.T. was suspended three times in one month at Belle Haven," says the boy's 52-year-old step-grandfather, Edward Grooms. "He was picked up by the police once for breaking a bus window while passengers were still riding it." J.T. may be the academy's brightest student, says Damon Horn, J.T.s teacher. In order to keep him busy and calm for a while, Horn had to give J.T. college-level math problems. But usually J.T. finished his work a little too early, and "then [looked] around the room to look at who else he can bother," says his father wearing a 49ers baseball cap tipped to an angle. J.T.'s young life, in many ways, bears an eerie resemblance to that of his father's own troubled past. When J.T. was five years old, his mother sent him to East Palo Alto to live with his father’s mother and step-father. And at that time in 1986, Grooms said he had been selling heroin and cocaine out of his house. Four years later, a nine-year-old J.T. witnessed the police knocking down his door to arrest his grandparents for selling drugs. Grooms pleaded for the courts not to send J.T. to a foster home and denied that his wife, Jolly Coleman, had anything to with his crime. Instead Grooms served an eight-month sentence in San Quentin and finished his four- and half-year sentence at Solano State Prison. He has been out of jail for three years. "I'm still on parole," says Grooms. "I sold drugs because of the money I made." Grooms was receiving General Assistance, which was only $900 a month to support his wife, J.T. and his adopted 14-year-old son, Compton. He didn't have enough money to support his family. When he started selling drugs he made approximately $400 on weekdays and $1500 on weekends. "Everything that good you think it'll never come to an end," says Grooms. Today, Coleman said his son reminds him of himself. A 15-year-old head shot of Coleman sits on one of the antique coffee tables in the living room and for one instant it looks just like J.T. "You see one, you see the other," says Grooms. "Like father, like son." Coleman also had behavioral problems in school, but was known as being extremely intelligent. "My favorite subjects were history and English," says Coleman. "I used to cut class a lot, but I never got kicked out of school." Since Coleman barely knows his father, he wants to make sure that he becomes a positive role model in his son's life. "When I'm not around he goes crazy," says Coleman. "It's mandatory for me to be here." But Coleman’s parole officer, Veronica Sepulveda says J.T.’s father isn’t as dependable as she’d like — she is having difficulty finding him. "It's getting hard," she says. Coleman's mother Jolly said people had informed her that her son, was "up to doing no good again," she says. "I haven't seen Terry in two weeks. I told him he needs to be around his son more." After being released from jail several weeks ago, Coleman said he would stay on the good path and find work. Now he says he has been working as a home attendant and receives a salary of $487 every two weeks. "I worked with them before I got locked up," he says. "I take care of this woman in Redwood City who feels suicidal at times." He says he plans to apply for work at a computer disk company in San Jose. Coleman says as soon as he gets a place to live he's going to take J.T. away from Grooms and Jolly Coleman. "They just want to take my grandson away from me," says Jolly Coleman. A little after 1:00 p.m., J.T. storms into the house with his hand out to his father. Terry responds, "Didn't I give you money yesterday?" J.T. says, "I ain't got nothing in my pocket today." Coleman reaches in his pocket and pretends he has a $100 bill, and tells J.T. he can't break it. He then instructs J.T. to ask his wife for $5.00 when she gets back from fishing. Smiling nervously, Coleman shakes his head and said, "I don't know what to do with my son." He reflects on the years he spent in jail and how painful it was not seeing his son grow up. "It was stressful for me," says Coleman, as he chokes back his tears. "Those years I could never buy back. Jail is the second best thing to hell." While he was incarcerated, Coleman says he managed to learn how to type 160 words per minute. He also studied Arabic and Hebrew and converted to the religion of Islam. The words "Allah Akbar...," roll off Coleman's tongue as he begins to speak in Arabic. Interrupting his prayer, a woman dressed in a hot pink tank top and shorts asks Coleman if he wants to go with her to shoot a game of pool. As if awakened from a trance, Coleman jumps up from the dining table, almost spilling over a bowl of oranges and apples onto the floral table cloth. He looks for his black ski coat and runs toward the door. But before he is able to exit, Grooms calls Coleman to talk to J.T., who won't listen to him. Coleman goes upstairs and tells J.T. to clean his room and to listen to his step-grandfather, who has been married to his mother for 20 years. Then Coleman promises J.T. that he will take him to live with him. J.T. looks up at his father, and begins to clean up the trash in his room. "Would I get my own room?" he asks. "Of course," says Coleman. "You can't sleep with me and my wife." Coleman currently lives in Redwood City with his wife, Kim, to whom he has been married to for five years. Kim has been dating J.T.s father since she was 13 years old. J.T.s biological mother lives in Louisiana and is nine years older than Coleman. "I met her in a (night) club with my uncle's wife," says Coleman, who had been visiting his mother's family in Louisiana. "We stayed together for a little while, but it wasn't real." J.T.s mother is 44 years old and has 13 children with two grand children. She tried to keep J.T., but when he reached five years old, Coleman wanted to raise his son. From the time he was an infant, J.T. moved back and forth from his mother and father. When Coleman went to jail, J.T.s behavior became uncontrollable. Coleman's mother, Jolly, thought it would be best to send him back to his mother in Louisiana. "He didn't go to school for a whole year down there," said Grooms. "He has problems with women telling him what to do." Coleman begins reciting rap to Ice Cube's music that is blaring from J.T.s cassette player. J.T. watches his father in amazement and then continues to clear the dust and dirt from underneath his bed. Before Coleman leaves J.T.s room, he gives him a pound with his right fist and says, "I'll see ya later." |

J.T.'s Story |