Prison alternative changes lives, saves money

Twenty-one-year-old Montrel Henderson had been locked behind bars in San Quentin state penitentiary only a short time before the Oakland youth began to see the horrors of prison life. "I saw people get stomped and a guy's neck gushing with blood and another guy who's ear was hanging off from getting cut. That place wasn't fit for animals," said Henderson. Desperate, he prayed to God to help him get out.

After having been convicted for selling marijuana a second time and therefore violating his probation, Henderson had been sentenced to spend two years in one of several state prisons. First, Henderson was sent to San Quentin, arguably the most violent facility in the state, on a 90 day observation, as he says, "to see if I was penitentiary material."

San Quentin officials sent an evaluation to the Alameda County Superior Court testifying that Henderson was a model prisoner and not a hardened criminal like most inmates in the maximum security prison. It was at this point that Henderson's prayers were answered. Fortunately, Sentencing Judge Larry Goodman had a viable alternative available when deciding what to do with the second-time felon who did not seem to meet the typical inmate profile.

As he had done with 90 or so similar cases in the past year, Goodman sentenced Henderson to something called the "Underground Railroad."

Defined as an "alternative sentencing program," the Railroad plucks young (18-25), non-violent offenders, who do not have extensive criminal records, out of the system and places them under the guidance and supervision of counselors and job developers. Instead of serving a two to four year term in prison, these second-time felons spend that time going to school or working.

In the opinion of many law enforcement officials in Oakland, the program is succeeding. According to Goodman, thus far only 20 percent of participants in the Underground Railroad have committed another crime and been sent back to jail. He said these results are the opposite of standard probation, where 80 percent of participants return to prison.

Considering the skyrocketing costs of incarceration (it costs $70 a day for an inmate to be incarcerated in the state of California) and the boom in prison construction due to overcrowding (since 1985, the total number of inmates in the custody of state and federal prisons has more than doubled to nearly 1.6 million - an increase of 113 percent), this simple program seems to be an inexpensive alternative.

A typical reason many people end up in prison is that they commit a crime while on probation. Once a felon's probation is revoked, he can not return to probation unless he proves his innocence. This rarely happens however. After a felon's probation is revoked, he faces modified legal rules and procedures that make convictions significantly more likely. Every year 1,969 such probation revocations occur in Alameda County, 443 of which are for drug trafficking.

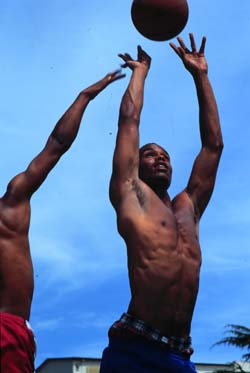

Montrel Henderson

Photos By Abner Kingman

Related Story

Montrel

Henderoson tries to break

cycle of crime and punishment:

It costs $70 a day for an

inmate to be incarcerated in the state of California

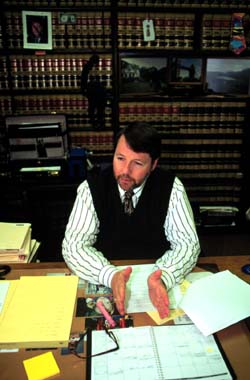

Judge Larry Goodman