WHO ARE WE?

CONTACT US

FEATURE STORIES

Caught in the cross fire: Is Beirut Ready for Tourism?

Marriage: Lebanese Style

Meet Lebanon's only Male Belly Dancer

Beirut Blues

A Visit in a Palestinian Camp

The Woman Behind the Walls

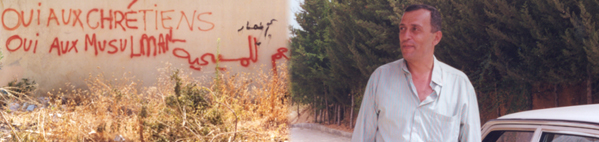

But for people like Jakhar, who didn't have the resources to flee his ravaged country during the war, Lebanon will always be home, whether the Christians remain in power or not. Jakhar speaks only Arabic and knows a few words of French. Not enough to make him part of the French-speaking, European or U.S.-educated Christian elite. He grew up a farmer's son in Wadi Al Site, a small village in the Southern mountains and had to quit school when he was only nine years old. At that time, it became too dangerous for him to hike to school, two miles away from his village. "In the early seventies, when communal conflicts between the Druze and Maronites started all over again, we had to stay home if we did not want to get killed by the Druze," Jakhar said. His father died in 1981 from cancer and his mother died when he was very young. As a result, he had to support four brothers and two sisters. In 1983, they had to flee from the Chouf region, which lies southeast of Beirut when it was clear that the Druze had won the war of the Mountains. Too old to flee, Jakhar's grandmother and aunt were murdered by their Druze neighbors when they took over his village. The massacres of Maronites in 1860 had already resulted in their exodus from the region but the process was almost completed during the 1975-1990 civil war. "We had no choice. If we had stayed we would have all been massacred, said Jakhar."

Despite his anger and although many of his friends did, Jakhar always refused to join a Christian militia to fight the Druze. "I am not a fighter," he said. During the war he was hired as a security guard for the U.S. embassy. "I got hired because of my clean past," he said proudly. But after 15 years of a merciless civil war, nothing surprises him anymore. He has seen Christians and Druze kill each other, Christians killing Christians, Muslims killing their own brothers in Lebanon. "You can never take anything for granted, even peace," he said. "I work so hard that I don't even have time to look for a wife," said the handsome green-eyed, dark-haired driver.

Jakhar pays his taxi company no less than $330 per week for the right to drive, even though he had to buy himself the used Mercedes where he spends most of his day. Instead of complaining he feels lucky enough to have a job now in a country where unemployment reaches nine per cent according to official data, but 25 according to many economists. In his free time he goes back to his hometown of Wadi El Site where he is restoring the farm his father owned with the help of his brothers. After peace was signed between the Druze and Christians in 1992, Jakhar, like many Christians, was able to return to his native village. There he found a place with no people. Some had fled abroad, some like Jakhar, went to Beirut. "Our village used to have 1500 inhabitants. Now there are only 25 old people. The younger generation comes only to visit but there is no future there," he said. Nonetheless, Jakhar said he loves his village enough to want to settle there when he retires.

Many Christians have left Lebanon during and after the war: 500,000 of the 700,000 people who left Lebanon during the country 15-year civil war were Christians, and in the eight years since, it is estimated that 100,000 more Christians have also emigrated. Some are hoping to move back once the country gets rid of its double occupation (Israel to the South and Syria that retains some 35.000 soldiers all over Lebanon). Others, like Jakhar, mainly those who never had enough money to even think of leaving the country, are just trying to carve out a place for themselves, hoping that a regional peace will erase the scars of the war. While Jakhar is proud to be Christian, he is aware that he has to adjust to the new demographics. When asked whether he would consider marrying a Muslim, he said: "As long as I am in love and that I don't have to convert, I think I might, but I would like her to help me pay the mortgage." His biggest fear is not to find a wife, whether Christian or Muslim: "In Lebanon most women want to marry rich men and I don't have much," he said.

Back to Home Page