SCRAWLS ON THE

WALLS: Graffiti and Muralism in Mexico City

by Lina Katz

|

||||||

|

by Diego Rivera

|

||||||

Muralists Felipe Ehrenberg and Daniel Manrique participated in a resurgence of Mexico's muralist movement in the 1970s. Although influenced by the Three Greats, they forged their own artistic philosophies and styles, drawing on contemporary influences and events. With the invention of the spray-can in the late 1900s, writing on walls took on a different form and meaning in Mexico. Rawer in execution and expressive of a younger, more urban subculture, the art-from became known as graffiti. Ehrenberg and Manrique's generation of muralists find little connection with their work and this new form of spray-can muralism, while graffiti artist Pedro Van Lenger insists his work is an evolution of traditional Mexican muralism.

|

||||||

|

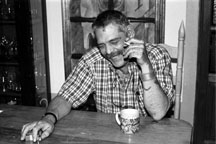

Ehrenberg

sits at his kitchen table in his home in Mexico City.

|

||||||

Born in a small village

which has since been swallowed whole by Mexico City, Ehrenberg considers

himself a General Practitioner of art, and refuses to let himself be categorized

or defined.

As a practitioner of public and performance art, He

views art as a dialogue betwen two people. "The Maker and the Watcher

become accomplices," says Ehrenberg. "The Maker just initiates

it. For the Watcher, the work of art never stops growing."

Community involvement in art is vital for Ehrenberg. In the late 1970s,

he formed a group called Grupo Processo Pentagono along with several other

artists. Together, they painted and directed the painting of hundreds

of murals throughout Mexico, using traditional and contemporary mediums.

Although he has used a spray can in his creations, Ehrenberg distances

himself from being called a graffiti artists. I

never called it graffiti art. I just called it art. I didn't do graffiti,"

he says. "I did it on the walls, and I thought it was very logical

to use spray cans," he says, taking a long drag off of his cigarette.

|

||||||

|

Ehrenberg prepares looks

through recent figure drawings.

|

||||||

"Giant companies created a tool--the spray can. After a while, people learned sophisticated ways of using spray cans, that these companies never thought possible," he says. "The tool is being appropriated by different clientelle, who "deface" whole cities. That marking of a city's skin bothers one part of the population, but to another part, it establishes all sorts of codes and messages."

For Ehrenberg, the

quality of graffiti ranges from "a dog pissing on a wall to a very

sophisticated works of art."

For Ehrenberg, graffiti art and murals have very different purposes, even

though both are public expressions of art. Whereas traditional

murals are signed by the creator, graffiti pieces are typically signed

with a "tag" or pseudonym. "Mural artists get empowered

or commissioned by their community," he says. "Graffiti artists

feel empowered. They take over a wall."

Traditional muralism is informed by a long tradition of specialized skills,

such as the fresco and mosaic-creation. Whereas graffiti artists have

only claimed sophisticated skills as of the invention of the spray can.

"They made art history, but they didn't draw from it," he says.

Still, Ehrenberg does

see some validity in sophisticated graffiti art. "Graffiti

artists pull from their surroundings, which artists have always done,"

he says. "Art

is a biological need for humans and graffiti is one way that people meet

that need."

|

||||||

|

Manrique poses in front

of 1999 mural in painted in Tepito.

|

||||||

Wearing

only black, Daniel Manrique stands in stark contrast to his vibrantly

colored murals.

Throughout his 60 years, he has painted hundreds of murals throughout

Mexico City. A native of Tepito, Manrique feels drawn to paint the familiar

scenes of his childhood. He also celebrates the lives of those who work

with their hands. "I paint the shoemaker, welders, bedmakers and

mechanics," says Manrique. "All their work is done without official

schooling."

Although he is one of Mexico's most famous living muralists, Manrique

does not respect the work of Siqueiros, Orozco or Rivera. "I understand

Rivera was an excellent painter, but he didn't create anything,"

he says. "He was an excellent learner, but he didn't leave anything

new behind."

|

||||||

|

Manrique's vibrantly colored

murals often depict the struggles of laborers and slaves.

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

Van Lenger talks on a

pay phone in Mexico City, near a graffiti wall.

|

||||||

On

a chilly night

in October 1996, Pedro Van Lenger was illuminated only by the moonlit

sky, as he spray-painted a wall in La Condesa, Mexico City. The only sound

around him came from the intermittent rattle and hiss of a spray can as

it spewed paint in fine lines and bursts.

"A graffiti wall is a mural in my opinion," says Pedro Van Lenger.

This particular graffiti wall was painted in remembrance of Mexico’s 1968

UNAM Massacre and depicted a snake in a dove’s claws, surrounded by Zapatistas.

Van Lenger has

painted both commissioned murals and self-commissioned graffiti walls.

The difference, he says, is mostly permanence. "Graffiti is more

temporary than a mural," he says. "Since the work is not commissioned

and is often illegal, no one owns it." Graffiti artists knows their

work may be buffed over by authorities or property owners the day after

they throw it up on the wall, creating a different impetus for creation

than is the seed for most artists who hope to gain notoriety through eventual

exhibition.

Van Lenger’s La Condesa wall has since faded and has been tagged over by other graffiti artists and gangs. Unconcerned about his own work’s transience, Van Lenger believes in this dialogue that public art, including graffiti, inspires in a community.

|

||||||

|

Colofrul

grafifiti covers many of Mexico City's walls., representting symbols

of youth and underground culture.

|

||||||

This young graffiti

artist and muralist defends his craft against the anti-graffiti sentiments

of some of his predecessors, like Daniel Manrique. He attributes Manrique’s

harsh judgments to a "generation gap" and insists that graffiti

walls often have sophisticated political messages. In 1997, Van Lenger

traveled to San Miguel, where he spray-painted a war zone scene in protest

of human rights violations happening in Chiapas. The wall-turned-canvas

depicted body parts, a severed head, clustered dollar-signs in the shape

of bushes and a river of blood dripping to the wall’s edge.

Van Lenger recognizes graffiti’s validity, even if the works explore an

artist’s immediate environment, rather than political or historical themes.

"Murals are supposed to have educational content," says Lenger.

"Graffiti has that, even if it’s just paintings of Cadillacs and

weed. That’s still valuable information. It creates a dialogue and brings

it out there."

For Van Lenger, graffiti is not only expressive of a particular community, it is also reflective of contemporary artistic trends. "Look at modern art. No one paints Rubens anymore. Modern art is so distorted, like Rothko," says Van Lenger. "Similarly, graffiti is an evolution of Rivera’s muralism."