Sweat Lodges in Wyoming

Sweat Lodges in Wyoming

![]()

The Chokecherry Cafe is a tiny, white frame grease joint on the Shoshone-Arapaho reservation in Ethete, WY. Inside, men with weathered faces and big bellies put away burgers, fries, and the house specialty, puppies in the straw, also known as corn dogs, around the patron chokecherry plant that pushes its way through a crack in the linoleum floor. It's hardly what one would picture as a spiritual place. But a framed poster on the wall reads, "But those who wait on the Lord will renew their strength. They will soar on wings like eagles, they will run and not grow weary, they will walk and not be faint (Isaiah 40:31). This verse is not accompanied by idyllic pictures of clouds or an artist's rendering of heaven; the words scroll across a painting of an Indian warrior dressed in eagle feathers.

St. Stephen's has been a fixture in Ethete since 1900.

Ethete's Wind River reservation, spread across rolling Wyoming plains and surrounded by snow-capped mountains on all sides, is a prime example of the hybridization of traditional Native American and Christian beliefs on modern reservations. This melding began as a matter of necessity. To preserve their own methods of worship and placate the missionaries, Natives had to combine the two. "That kind of started when the missionaries came here," said Arapaho elder Stanford Addison. "In order to keep our traditions alive, we had to incorporate [Christian rituals and symbols]." And the traditions that have remained clearly show the mark of Christianity-- sweats that incorporate crosses, Native American church services that treat peyote as a sacrament. But this does not preclude identity problems. If an Indian becomes a Christian, is he or she still Native American? Many don't think so.

I asked one of the men I worked with, Arleigh Armajo, Director of the Northern Arapaho Housing Improvement Program, if he considered himself to be a Christian. He said no, despite the facts that he was educated in a Catholic school and that he believes in Jesus' death and resurrection. "I graduated from Catholic school and then I turned traditional- traditional ways most of my life," said Armajo, a tall reticent man with tinted glasses. "I think traditional and Christianity are compatible but traditional is the way I believe." To Armajo, the Catholic priests who taught him in school worship the same God he does; Armajo just prefers traditional methods. He was reluctant to say much more. "I think you are a living example of what Christianity is," Bob Turley tells Armajo quietly. Turley is a year-round Group employee who has led workcamps on the reservation for more than twenty years. Armajo ducks his head. He is so embarrassed by this statement that be declines to answer any more questions. Instead, he offers to take me to visit some of the reservation elders, who can "answer better." Later, Turley, a white "liberal Catholic" who almost looksNative American with his turquoise jewelry and Indian-style belt buckle, elaborates on his comment. "I think a lot of times Arleigh's one of the most Christian guys I know," he said. "Taking care of people, hunting for his family. He does a lot of things for others that people don't know about. In a very quiet way."

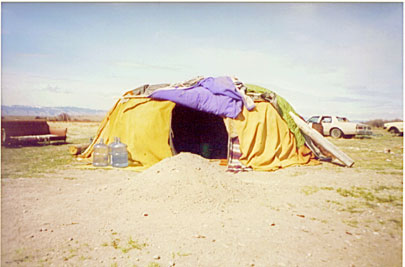

A couple of days later, Armajo and I are riding in his dusty pick-up truck to see Elder Crawford White. Explaining to me that it is customary to take elders tobacco in exchange for wisdom and counsel, Armajo stops by the convenience store so I can pick up a pack of Marlboro Lights for White. When Armajo tries White's cell phone, however, there is no answer. Since he's not home or not answering his phone, we decide to visit another elder. Stanford Addison lives on a dusty back road of the Shoshone-Arapaho reservation in Ethete, WY. Rolling his wheelchair slowly down his driveway, Addison appears too young to be an elder, with his long black hair and sweat-stained white tank top. We have made a second quick stop at the convenience store to pick up a pack of Kools, Addison's tobacco of choice. Feeling awkward, I produce the cigarettes, which Addison accepts without a word. He considers himself to be both a Catholic and a traditional, and his house itself is a juxtaposition of Native beliefs and Christianity: a crucifix hanging over the door and a sweat lodge out back. The lodge is a tiny low-lying circular building topped with camel-colored skins carefully arranged to resemble the turtle the Arapaho believe brought their land.

Addison's sweat lodge.

Sweats are one of the few remaining Indian traditions. The ritual of the sweat lodge has diffused to almost all of the Native American tribes in the Northwest In the 60s and 70s, Addison and the others had to hide their sweatlodges, but now "even the Mormons" come and participate in sweats, he tells me over a glass of his wife's iced tea. During a sweat, men and women gather inside the crowded lodge with fire-heated stones and a bucket of water. The people taking part in the ceremony draw dippers of water to represent their requests for prayer. Just as it has with many of the other remaining Indian traditions, Christianity has left its mark in the sweatlodge. It is customary for someone to draw a cross on the ground with water, which represents either a belief in Jesus or the coming of the Bible, depending upon who you ask. "That represents the coming of the Bible," said Addison. "Because when we're in that sweat we're not there to discriminate against prayer. All these ways are the ways of the Creator." Addison doesn't see any problem with combining the two halves of his spiritual life. "I go to church when I have a need," he said. "The fathers come here and sweat and they consider this my place, my way of prayer, I consider the church their way, their way of prayer. Instead of fighting different ways of prayer, we accept them all." But praying in the sweat lodge, which he does several times a week, holds a special significance for Addison. "Prayer is more intense in the lodge," said Addison. "Last time I was in church it seemed like everybody was trying to appear to everybody else and not to the Creator. In the sweat you can't see each other so we believe we appear to God."

The intensity described by Addison has attracted many Christians to the lodge as well. Turley considers the first sweat he attended with Armajo was a landmark in his spirituality. "What really hit me was that the praying I heard on those sweats was so much more intense, down-to-earth and simple than I've seen in most churches," he said. "Very intense, very respectful." Ever since then, Turley has incorporated Native American practice in his faith. "In my faith, I felt no conflict," he said. "If you really examine it, a lot of the basic concepts are the same-- community, helping the less strong, family. We could learn a lot from how they take care of their families. No one is refused shelter and food." But right now it is the work campers who are taking care of Addison's home. Six of them are outside as we talk, hammering away at a wheelchair ramp they have built on the front of his home. They cause him to reminisce about misunderstandings between Christians and his people. "We believe everything has a spirit," he said. "That's where the misinterpretation came when people thought we were praying to those spirits. But we always knew there was just one Creator." He's pleased with the teenagers performing repairs on his home. "I think it's good because they're trying to make a balance now-- they're helping our elders and understanding us a little better because we don't have that communication barrier anymore [of thinking Natives prayed to spirits]." Addison's wife Sandy agrees. "I've just come to the point where I just believe everyone should respect each other's religions," she said from behind her copy of Laura Surya Das' "Awakening the Buddha Within."