|

|

GOLD!

GOLD IN

CALIFORNIA!

By David

Littlejohn

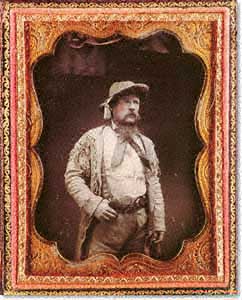

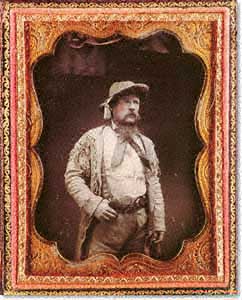

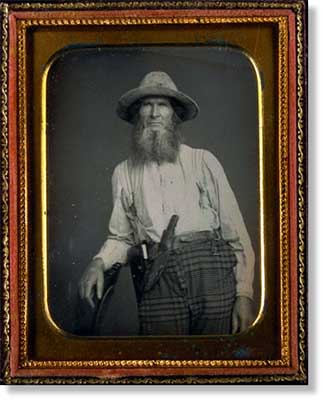

Unknown Maker, George Bomford in Buckskins

andSuspenders, quarter plate daguerreotype.

Collection of Matthew R. Isenburg

Courtesy of the Oakland Museum |

The Oakland Museum of California is

housing the central event of the state's

commemoration of the 150th anniversary of the

discovery of a small gold nugget at Sutter's Fort

(near present-day Sacramento) in January 1848,

and the frantic emigration of hundreds of

thousands of people to California during the next

four years, most of them hoping to find more

gold. At the museum, a team of curators headed by

L. Thomas Frye has assembled more than two

thousand 19th Century California artifacts into

an ethically updated reconstruction of the Gold

Rush and its dubious effects; then put together

separate exhibitions of contemporary artwork and

daguerreotypes illustrating the event. |

This

three-part exhibition, entitled as a whole

"GOLD RUSH! [the capitals and exclamation

point are the museum's]: California's Untold

Stories" is the most costly ($3 million) and

ambitious display the Oakland Museum has

undertaken since it opened in 1969. The

historical portion leads the visitor through a

circuitous series of tableaux and displays,

guided by personal earphones through an elaborate

CD-ROM audionarrative--part lecture, part

dramatic recreation--which is included in the

cost of admission. As you amble from one setting

to another, voices in your ear automatically pop

on to tell you about the basic events depicted:

the lives of pre-Gold Rush Californians, the 1848

discovery, the spread of the news throughout the

states, preparations for the journey, the mass

emigrations of 1849, and so forth. Along the way

we hear sounds of ocean storms or creaking wagon

wheels, actors reading from historic letters and

diaries, and the jaunty Ken Burns-style

harmonica, fiddle, and accordion music that has

become electronic shorthand for "American

History."

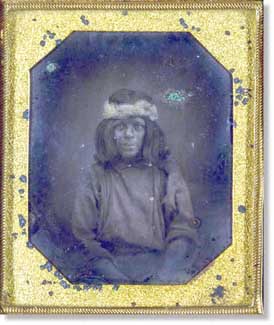

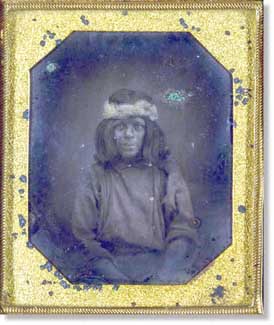

Unknown Maker, Miner with Shovel,

Quarter plate daguerreotype.

Collection of the Oakland Museum

of California

|

At more than 150 stations en

route, you can punch a number on your

portable CD player to gain additional

information, much of it blasting the

49ers for their greed, intolerance, and

environmental insensitivity. This

obviates the need for wall labels or

placards, and pleases people impatient

with silent, inactive museum displays.

(The show is heavily geared towards

school tours, and offers a separate audio

tour for young children.) But it does

tend to force a response, even though the

mellow voices in our ear occasionally

invite us to think for ourselves. (Was

Joaquin Murietta an evil bandit or a

Mexican Robin Hood? Was the devastation

of the California landscape worth the

huge profits of hydraulic gold mining?) |

|

|

The exhibits are housed in 10,000 square

feet of galleries walled in canvas stretched

between pine timbers. They vary from standard

museum arrays of costumes, weapons,

pictures,letters, oxbows and the like to

"interactive" side shows: you can put

your hand under the original nugget (encased in

Plexiglas)found at Sutter's, swirl your own

panful of gold and gravel, guess the best place

on a map to strike it rich. Among a few

impressively large objects are a reconstructed

miner's cabin from Siskiyou County, a Wells Fargo

coach, the stern of a Gold Rush era ship dug out

from under San Francisco, a set of very

uncomfortable looking wooden ship bunks, and some

huge iron tools of early industrial-era mining. A

mock "theatre" in the middle of the

main hall shows imaginary 1850s Gold Country

entertainers on a large video screen.

|

Isaac Wallace Baker (1818-c.1862), Native

Californian, Sixth platedaguerreotype.

Collection of the Oakland

Museum of California |

The centerpiece exhibit is a diorama of

ten life-sized mining camp denizens, going about

their business in five supposedly independent

locales connected by an imaginary stream. Their

mining techniques and settings look authentic

enough.What appears slightly tendentious (though

it may appeal to the museum's visitors and

funding sources) is that, of the ten fiberglass

figures, two are women, two Chinese; one is

Native American, one African American, one

Mexican, and one Hawaiian. Of course, the vast

majority of the gold seekers who came to

Californiabetween 1849 and 1852 were young white

men from the thirty United States. But this

exhibit is designed to tell "California's

Untold Stories," and in particular those of

people in California other than young white men. |

In the exit gallery hang enlarged

photographs of contemporary Californians, whose

words are the last we hear on our earphones.

Novelist James Houston suggests we could learn

from the Indians, who were here 10,000 years

before 1848, how to thrive in California without

destroying it; his wife Jeanne

Wakatsuki("Farewell to Manzanar") finds

a way to work in the state's World War II

internment camps for Japanese-Americans. Julia

Parker, a Pomo Indian basketmaker, says, "In

spite of all effort to exterminate California's

first people, Indians are still here." David

Brower denounces the Gold Rush for the damage

itdid to his state and the environmentally

careless attitudes it fostered. Former Governor

Jerry Brown (now running for mayor of Oakland)

waffles in typical fashion about California's

"throbbing" potential. Teenage

immigrants from Mexico and Ethiopia mouth pieties

about diversity and the future. On the whole,

California comes out of this show as a pretty

shameful place, tainted from birth by any number

of original sins.

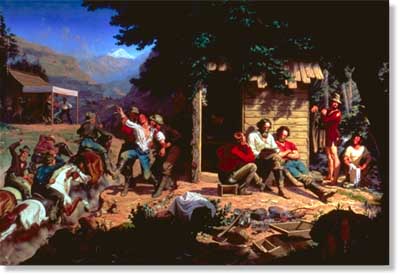

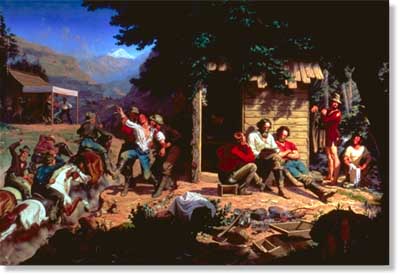

| Unfortunately,

much of the Gold Rush art on display

tilts the miner's scales in the other

direction, sentimentalizing life in the

mining camps into Victorian magazine

illustrations. Miners pose in heroic

attitudes overlooking spiky Alpine

vistas, or die in the snow alongside

faithful dogs. The best-known painting

here, Charles C. Nahl's "Sunday

Morning in the Mines" of 1872,

squeezes five separate episodes into one

big bright Caravaggio-realist cartoon.

Works like this, or Henry Burgess's

"View of San Francisco in 1850"

(painted in 1878), or Ernest Nargot's

rustic cabins in leafy Barbizon glades

(painted in the 1880s) reflect how

quickly anostalgically distorted vision

of the Gold Rush entered into legend. The

art curators, too, are perhaps overly

eager to criticize Californians of 150

years ago by the enlightened standards of

1998. But the argonauts' own

contemporaries oftensaw them through the

filters of equally deforming aesthetic

and ethical standards.

|

| Sunday Morning in the

Mines |

Charles Christian Nahl

(1818-1878), 1872, oil on canvas. Crocker

Art Museum,

Sacramento, California, E.B. Crocker

Collection

Art courtesy

the Oakland Museum of California

|

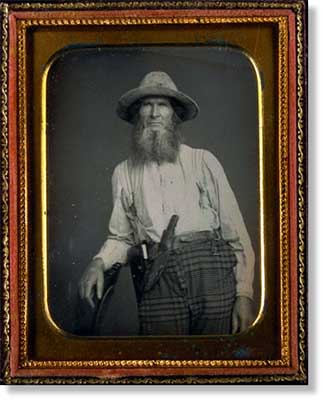

Uknown Maker, California

Forty-Niner, Quarter plate

daguerreotype. Collection of Amon

Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas,

P1983.20Courtesy

of the Oakland Museum of California

|

The unique and fragile

daguerreotypes and ambrotypes

(reproducable photographson paper arrived

in 1860) offer the surest piece of

history here. Most of these are tiny

silver plates preserved behind glass in

velvet-lined cases, installed behind more

glass in rooms that are kept very dark.

Looked at from an angle, the images

disappear; ceiling spots cast distracting

reflections. When the galleries are

uncrowded, you can see them all more

clearly in two albums of reproductions

(with accompanying explanations)

installed at the entrance. The 15-second exposures required

for these early photographs tended to

make most of their human subjects look

gimlet-eyed and grim. But these 154

images bring to life an astonishing cast

of characters: miners posed in required

49er costume (their woolen workshirts

often tinted red or blue), with

appropriate props: picks, pans, guns,

nuggets, bags of gold. Later come worn,

unsmiling women with children, corpses in

coffins, memorial shots of gravesites to

send back home. Venturing outside their

tent or store studios, early California

photographers captured you-are-there

views of diggings, cabins, and mining

camps, as well as the streets and harbor

of infant San Francisco.

|

|

Here

again the heavy hand of the contemporary critic

can be felt. Images ofIndians, Mexicans, and

Chinese are accompanied by texts describing their

mistreatment at the hands of Yankee emigrants.

"In their unrelenting quest for gold, the

forty-niners decimated the natural environment

around them" is the curators' way of

explaining the cut-down trees, the dammed and

diverted rivers (phenomena apparently unknown

east of the Mississippi) in a picture of miners

at work. A primitive tent-store in a the

mountains is seen as "embodying the crass

commercialism of the gold rush."

|

Despite a

tendency to nag the past for not being as wise and

tolerant as thepresent (and a degree of dumbing-down in

the audio tour), the historical exhibition has been put

together with considerable ingenuity, and is well worth a

couple of hours' visit. The daguerreotypes add a valuable

human dimension. An even better way to bring the Gold

Rush to life, for people who still read books, might be

to spend a few days with the letters of its participants,

in compelling works like J. S. Holliday's "The World

Rushed In," Malcolm Rohrbough's "Days of

Gold," or any one of many published collections.

Graphic image courtesy of the

Oakland Museum

The Gold

Rush Exhibit

|

The daguerreotypes and the

history display stay in Oakland through July 26.

Theformer then go (with the paintings) to the

National Museum of American Art at the

Smithsonian (Oct. 1998-March 1999). The latter

travels to the Gene Autry Museum in Los Angeles

(Sept. 1998-Jan. 1999), then to Sacramento's

Memorial Auditorium (July-Oct. 1999). The two

exhibitions of images will be shared with

Sacramento's Crocker Art Museum, which helped

create them--the paintings thisfall, the

daguerreotypes in Fall '99. Meanwhile, the

Oakland Museum's website (www.museumca.org/goldrush) offers a good sampling of all

three exhibitions, including two nifty 360-degree

panoramas of the historical displays. |

|