A Retelling of Gold Rush History: The Lives of Chinese Miners

by Nina Wu

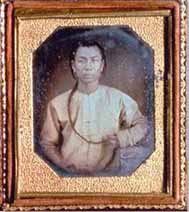

In

the 19th-century daguerrotype taken by Isaac Wallace

Baker , a Chinese man dressed in a light-colored mandarin

shirt holds his long braid in one hand, lookingdirectly

at the camera. The man in the photo has no name, but his

unsmiling face looks weather-worn, strong and dignified.

Portrait of a Chinese Man, c.

1851

Photo Image

Courtesy of Oakland Museum

The photo is just one of the items

included in the Oakland Museum of California's

three-part, historical exhibit, entitled GOLD Rush!

California's Untold Stories.. Taking an innovative

step, the museum is the first in the Bay Area to present

the state's history from a new perspective — one

which tells the stories of the Chilean, Hawaiian,

African, Native American and Chinese populations during

that era.

“When people talk about the Gold

Rush, they have a certain image in mind of white

forty-niners,” Asian Cultural Program Coordinator

Ming-Yeung Lu said. “But in fact, the Gold Rush was

a major, international event that drew people from all

over the world.”

“When people talk about

the Gold Rush, they have a certain image in mind

of white forty-niners. But in fact, the Gold Rush

was a major, international event that drew people

from all over the world.”

—

Ming-Yeung Lu

Asian Cultural Program Coordinator

|

Like

many others from throughout the world, the Chinese had

dreams of finding gold in a land they called Gum Shan

— the Gold Mountain. Those who sought gold and

adventure sailed more than 5,000 miles across the Pacific

Ocean's rough waters, only to discover upon their arrival

that they were still 150 miles from the gold mine sites.

“A lot of them thought you could

come and pick up gold anywhere,” Lu said. “But

the reality was different. The prices of gold had dropped

tremendously and the price of food and lodging here was

very expensive.”

The US census

recorded a total of three Chinese residents in California

as early as 1848, when the Gold Rush broke out in the

foothills of the Sierra Nevada. The count increased to

300 just one year later and by 1852, grew to 30,000.

“One thing we try to emphasize,” Lu said,

“is that the reason the Bay Area is such a diverse,

multicultural area really started from the Gold Rush

era.”

In the Gold Fever portion of the

exhibit, visitors to the gallery will see the recreated

arheological site of the earliest Chinese store in

California, excavated from beneath the corner of

Sacramento and Kearny Streets in San Francisco.

The riches of the Gold Rush were, in

fact, what transformed San Francisco from a small town to

a bustling, industrial city. “The cosmopolitan

aspect of San Francisco developed very early,” Lu

said. “Those who settled there were mostly

well-educated doctors and lawyers. They brought with them

a high level of culture. If you read all the accounts,

you'll find that people were fascinated by all these

different cultures around them.”

That appreciation for culture included

an appetite for Chinese cuisines, Lu said. He cited some

written accounts by settlers who wrote of

“exceedingly palatable” dishes served up by

“celestials” (the Chinese).

Visitors to the audio-guided exhibit

will get a glimpse of a Chinese mining camp next to a

display of Native American tools, baskets and

arrowpoints. They will also learn about the Californios,

the members of great land-holding families and of

the Spanish, missionary explorers who came to California

looking “for glory, God and gold.”

History is retold

with new voices and a new awareness of the destruction

the Gold Rush caused in its wake, both of the Native

American population and the environment.

The audiotape includes the dramatized

voice of early immigrants telling their own stories

— in English, Cantonese or Spanish — as one

strolls pass life-sized figurines hard at work. “In

the Cantonese audio-tour, there's a segment where they

dramatically re-enacted the letter of a miner to his

family,” Lu said. “It was written by a white

miner, but in Cantonese, it`s still very vivid. To me

this signifies that although there were cultural

differences, a lot of the feelings these Chinese miners

had were very similar to feelings the other miners

had.”

Along with James

Marshall's first piece of gold in a display case,

visitors will seea large, spinning globe that pinpoints

where all the gold-seekers came from — whether by

land or by sea.

During the Gold Rush, the Chinese were

the largest group of miners other than the white miners,

according to Lu. Most came from the southern coast of

China. Since the Chinese proved to be effective miners,

resentment grew and they became “an easy mark”

for foreign mining taxes in 1851.

“I think all the ethnic groups had

tensions with one another,“ Lu said. “But the

foreign miner`s tax was mainly aimed at the Chinese

miners because at that point, they constituted the

largest group of non-white miners.”

“A lot of the white miners at

first willingly sold the Chinese these abandoned claims,

thinking the Chinese were just simple-minded people,

stupid enough to take over these mines they considered

worthless,” he added. “But the Chinese worked

these mines very thoroughly and it turned out they were

hardly worthless, that they could still, in fact, mine a

lot of gold from them, at which point the white miners

became envious and antagonistic.”

Not all of the Chinese were miners.

Some became storeowners, merchants and laundrymen who

settled in the San Francisco and Sacramento areas. Lu

points out that the origin of Chinese laundry businesses

may have begun during the Gold Rush period. “A lot

of the miners were men not used to doing women's

work,” he said. “So they would send their

shirts all the way back to Hong Kong to be laundered.

That`s when a Chinese enterpreneur thought of the idea of

starting a laundry.”

Wah Lee, the first Chinese laundry

business in San Francisco, opened on the corner of

Washington and Grant Streets in 1851. It cost $5 to

launder a dozen shirts, a bargain compared to the $12

price charged in Hong Kong. By 1870, there were 2,000

Chinese laundries in the city.

Stockton resident

Lani Ah-Tye said her great-grandfather, Yi Lo Ty, ran a

general merchandise store in Plumas County. He was also a

mining contractor. “His great advantage was that he

spoke English,” Ah Tye said. “He was like a

liaison between the Chinese miners and the others.”

Ah Tye has spent several years researching and piecing

together the history of her family in the United States

for a book to be published this Spring.

Unlike most of the other Chinese miners

during that century, Ah-Tye said her great-grandfather

requested to have his bones buried in the United States

rather than sent back to China. His bones, in fact, are

at the Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland.

“With the publication of this

book, I feel like I've come full circle,” she said.

“It's been 26 years, so it's been a long journey. I

did not realize our roots went so far back. In working on

this, I discovered that I'm really more American than I

am Chinese.”

Ah Tye will speak about her personal

journey at a Museum-sponsored panel in June, along with

documentary film-maker Loni Ding and Bill Ong Hing,

director of the immigrant legal resource center in San

Francisco. They will address the relevance of the Gold

Rush legacy to Americans in California today.

|