Picturing

a New Country

A political cartoonist's past activism translates into present-day

success.

By David Gilson

CAPE TOWN, South Africa, April 2 — On the back wall of Jonathan Shapiro's studio hangs a poster of cartoon anti-apartheid activists marching, protesting and taunting policemen with pig snouts. When he first published it in 1987, the apartheid government did not find it amusing. It banned the poster and Shapiro went into hiding.

The poster is a reminder of how much the South African political scene has changed since Shapiro began satirizing it nearly two decades ago. Activists who once ran from the police now run the country and the constitution protects freedom of expression. And Shapiro, a former radical underground artist, has become the country's most popular political cartoonist.

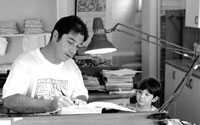

Jonathan Shapiro, AKA Zapiro, went from being an underground artist to South Africa's best-known cartoonist. As his 4-year-old son looks on, he works in his Cape Town studio. Photo by David Gilson. |

"I have a very free environment to publish," says the 40-year-old artist, who is better known by his penname, "Zapiro." In the past six years, he has chronicled almost every major event in South Africa's transition from apartheid to democracy and he has poked fun at all aspects of life in the new South Africa, from corruption and crime to soccer and Mandela's love life.

Though his politics are usually left of center, Shapiro is quick to point out hypocrisy wherever he sees it. He does not spare crooked officials, unscrupulous politicians or anyone who thinks they are above reproach. Perennial victims include former apartheid-era leaders, firebrand Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, Zulu leader Mangosuthu Buthelezi and of course, Bill Clinton.

Shapiro's boldness has earned him a diverse group of devoted fans. His cartoons appear in The Sowetan, a black tabloid with over one million readers, and two smaller mostly-white newspapers, The Sunday Times and the Weekly Mail & Guardian. Four collections of his cartoons have been national bestsellers.

"He's marvelous," says Philip Makubela, a Johannesburg chauffeur who reads The Sowetan. But Makubela, who has posted an enlarged copy of one of Shapiro's Mandela cartoons in his home, is surprised to learn that Shapiro is white. "But he's so perfect!" he says with a mixture of admiration and astonishment.

Makubela eagerly followed Shapiro's recent cartoons about the imprisonment of right-wing Afrikaner agitator Eugene Terre'blanche, popularly known as "E.T.," for severely beating a black man. In one cartoon, prison guards mock a dopey-looking Terre'blanche as he waits in his underwear to receive his inmate's uniform. They point to a pay phone and ask him, "E.T., phone home?"

Shapiro's biting sense of humor is balanced by a sense of humanity. "He's got a very razor-like pen and that's very effective," says Philip van Niekerk, editor-in-chief of the Weekly Mail & Guardian. "But he's not mean."

In person, Shapiro is remarkably earnest and relaxed for someone who makes his living making fun of people on deadline. He lives in Cape Town with his wife, Karina, and their two children in an airy house filled with toys and knickknacks. Dressed in jeans and a t-shirt, with earrings in both ears, Shapiro starts a typical day in the kitchen, where he makes coffee as his 4-year-old son talks excitedly about his favorite cartoon programs.

|

Shapiro sketches Nelson Mandela, one of his few sacred cows. Photo by David Gilson. |

He retreats to his ground-floor studio to work. There, surrounded by comic books, old drawings and sketchbooks, Shapiro sifts through the day's news for inspiration. Choosing topics is not hard, he says, but finding the right approach can be tricky. "If I give myself a few days, I'm usually able to tackle a subject," he says.

Lately, he's been thinking — and drawing — about the ongoing debate about racism and free expression in South Africa. This March, the government's Human Rights Commission investigated allegations of racism in the media and caused a furor when it subpoenaed several newspaper editors, including the Mail & Guardian's van Niekerk, to testify.

Though Shapiro came out against the hearings, they also evoked a rare response from him: ambivalence. In one cartoon, Shapiro drew himself in front of his drawing board, musing out loud, "[T]he media is too white-dominated...Although that's ironic coming from a whitey cartoonist on a black paper...On the other hand, I find myself in the ‘white' camp that regarded the [Human Rights Commission] subpoenas as a threat to press freedom."

He says the inquiry appeared to target newspapers that had been critical of the government. He is concerned that he and other progressives might be seen as reactionary or racist when they question the African National Congress government. "The race card is being thrown around a lot by a certain part of the ruling elite," he says. As someone who campaigned against apartheid and now supports the government, Shapiro finds this "bloody scary."

Shapiro grew up in a liberal Jewish family in the Cape Town area. His mother taught him to question the status quo of life under apartheid. As a teenager, he made some defiant gestures, but he did not "take the plunge" into politics until his twenties.

In 1977, he enrolled as an architecture student at the University of Cape Town. At the time, all young white men faced compulsory military service. When he tried to change his major to art, he was told that he would lose his draft deferment. After a six-month fight, he was conscripted into the South African Defence Force in 1982.

He spent two years in the army, where he earned a reputation for being the "camp communist." He refused to carry a gun and posted anti-apartheid leaflets on base bulletin boards. The army harassed and investigated him, but it did not discharge him until he finished his full two years of service.

Returning to civilian life in 1984, he continued to lend his artistic talents to the anti-apartheid movement, creating posters, logos and illustrations for the newly formed United Democratic Front and the End Conscription Campaign. He started signing his work "Zapiro," a reworking of his high school nickname "Zap," which he thought sounded "too California surfer."

On several occasions, his artwork and activism got him in trouble with the government. In 1988, as his first gallery show was opening, the police detained him on suspicion of planning an illegal 70th birthday celebration for the then-imprisoned Mandela. (It turned out the police were looking for another Jonathan Shapiro, but they kept him in jail for six weeks, nonetheless.)

Shortly after his release, Shapiro received a Fulbright Scholarship to study at the School for Visual Arts in New York. Though already a talented artist, he had never had formal training. In New York, he studied with legendary cartoonists Will Eisner and Art Spiegelman, who taught him the craft of expressing complex ideas with pen and ink. "Storytelling is something that America is so good at," he says. A strong American influence is visible in his work. References to Mad magazine, "Beavis and Butthead," Walt Disney movies and "Star Wars" have appeared in his recent work.

The people and politics of South Africa remain Shapiro's primary sources of inspiration. On the wall across from his drawing table hangs one of his trademark caricatures of a beaming Nelson Mandela. The portrait, which is featured prominently on the cover of a recent book of cartoons about Mandela, evokes the hopefulness that accompanied the freedom fighter's term as the first president of democratic South Africa.

Shapiro says that Mandela is one of his few sacred cows. "I'm really sycophantic to him across the board," he says. His admiration for Mandela reflects the idealism that has always run through his work, even in desperate times. Former Cape Town Archbishop Desmond Tutu praised Shapiro for his "passionate desire to will this country and its extraordinary people into realizing their potential." Satire was once Shapiro's weapon for tearing down the system. Today, it's his tool for rebuilding it.