Guiding the

Lost Generation

They left school to fight apartheid. Today, unemployed and undereducated,

they fight their personal demons.

By Kamika Dunlap

Kids of Youth For Christ's Amakhaya's Children's Home pose for a picture and show off their art work. Photo by Kamika Dunlap. |

JOHANNESBURG, South Africa — Slouched in his seat, Marcel Houston took a few seconds to tighten his black head wrap and clear his throat before describing how he was shot in a drive-by attack.

"I was coming from my fiancée's house, and, because I was labeled a type of gangster, I got shot," said Houston, 21, from Newlands, a nearby township notorious for gang violence. "I got stabbed, I got beaten up. Tomorrow I'm going to walk past there and those guys are going to look at me - what can I do? It's just what I have to go through."

|

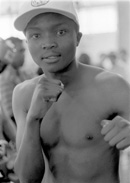

Punch the Bag, Beat the Streets Young boxers hope their fists lead them from crime and poverty. By Kamika Dunlap CAPE TOWN, South Africa — In the flashy new boxing ring built in 1997 as part of this city's attempt to host the 2004 Olympics, Chris Kibiti shadowboxes and trades punches with his sparring partner every day. Photo of Chris Kibiti by Mimi Chakarova. No Olympic medals will be won in the shiny arena. Cape Town lost the bid to Athens, leaving behind this reminder of a dream that didn't come true. But Kibiti, 21, hurries through the dangerous, dirt streets of the Khayelitsha shantytown to train in it nonetheless. "I'll fight for the world title," said Kibiti, ranked number one in the city's mini-flyweight division. "I hope one day I'll make millions." With his undefeated record in seven bouts, Kibiti plans to secure a better life for his family. "I'm staying in those shelters," Kibiti said, pointing to a makeshift shack of galvanized tin. "I want to take my family to the suburbs." An overcrowded township, Khayelitsha is one of Cape Town's most poverty-stricken neighborhoods. Kids loiter at stop signs, harassing drivers of passing cars for food and money. Most of its half-million residents live in shacks constructed with sheets of iron and pieces of collected wood. Some of Khayelitsha's young men come to the Oliver R. Tambo Centre, named after the former African National Congress leader, to escape the crime that surrounds them. Inside the boxing ring, engaging in one of the world's most dangerous sports, they feel safer than at home. The 10,000-seat arena may never be filled with fans, but it stands as a refuge, a place to sidestep the pitfalls of a township where gangs are plentiful and jobs are scarce. Many young people idolize Nelson Mandela, who took up boxing to keep fit while living underground in the 1960s, when he was organizing the armed struggle against apartheid. Thirty years later, the boxer became the nation's first black president. "We're engaging potential criminals in something that's more business-like," said David Mazomba, Kibiti's boxing promoter and a boxer for more than 15 years. "I want to get young people out of this situation." The white-walled two-story gym is bright and spacious. The basketball courts are coated with a heavy wax with fiberglass backboards at each end. Young boys and men, the youngest of whom is 10, filled the gym. Some walked around bare-chested with boxing gloves while others were dressed in karate gear. On the gym balcony young men rested for a water break and took in the view of the shantytown that surrounds them. "In this business sometimes I start in one place, and by the end of the day I end up in a better place," said Mzonke Fanna, 25, of Khayelitsha, as he described his experience traveling abroad for a boxing match. "London was a nice place, but I love Khayelitsha. I was born here," he said. Inspired as a child by Johannesburg boxer, "Baby" Jake Matala, Fanna plans to be a role model for young men in his community. "It's important to make kids feel closer to sports instead of corruption," he said. "The closer kids are to sports they can go anywhere." Recently, Kibiti was named "prospect of the year" and took a trip to Johannesburg, 775 miles northeast of here, for the professional boxing awards. It was his first time on an airplane. "It was a big achievement for him," Mazomba said. Yet this is only the beginning of Kibiti's quest to become the world boxing champion and to build a future for his family. On May 6, 2000 Kibiti is scheduled to fight for the International Boxing Organization title and he is hopeful. "With determination and desire I'll make it," he said. |

Houston isn't alone in his plight, seated in a circle with 25 other young men and women talking about issues of gangsterism and drug abuse in their neighborhoods. They are at the Wilgespruit Center, about 30 miles outside of Johannesburg, for a three-week retreat to assess their lives and plan ways to escape the cycle of violence in their neighborhoods.

"Most of us are school dropouts. There are no jobs for us, so we rob and steal," said Houston, who is a dropout and unemployed himself.

Glen Steyn, founder and director of Conquest For Life, an organization that attempts to provide young people with alternatives to crime, helps lead the discussion. "Nobody owes you anything but an opportunity," Steyn said.

Since 1996, Steyn has run the Youth at Risk Program, a camp geared to reach kids age 6 to 21 who are in trouble with the law, school dropouts, or unemployed. The Open Society Foundation, a philanthropic organization established by British billionaire George Soros, sponsors the camp. It is an effort to reduce South Africa's increasing youth crime rate and social problems, which have festered in apartheid's wake.

California, which saw juvenile arrests for violent offenses double between 1986 and 1995, recently enacted Proposition 21, a new law allowing prosecutors to try juveniles in adult courts and increase penalties for gang-related crimes. But South Africa is leaning toward diversion projects to reduce juvenile crime.

South Africa does not keep a separate tally of juvenile offenses. The National Youth Commission, established by Nelson Mandela in 1996 as part of the government's plan to address the challenges facing young people, estimates that criminals are getting younger. In 1990, the average young perpetrator was 22. By 1998, the age was 17.

Many young black South Africans left their classrooms in the 1980s to join the street battles against apartheid. Today they are undereducated and immune to violence, posing the greatest threat to the stability and prosperity of a new South Africa. The South African government established the National Youth Commission to address this problem, but has not committed sufficient funding for effective programs. Non-governmental organizations do the bulk of the work in juvenile rehabilitation.

According to a recent crime bulletin by South Africa Police Services, 43 percent of South Africa's young people are "at risk" — functioning in society but showing urgent need of help. Steyn's camp is a "safe space" for teenagers to share and develop life skill, according to a report on the effects and effectiveness of Conquest For Life's 1999 Youth Camps. The agency focuses on team-building, conflict-management, problem-solving and decision-making. Through such simple physical activities as crawling through a peer's legs or offering a piggyback ride, young people learn about building trust. The aim is to keep them from returning to gang-related violence and crime.

The teenagers at the camp were dressed in loose fitting jeans and soccer jerseys, and many of them wore head wraps and bandanas. Some had scars on their faces and arms. As Steyn lead the discussion some kids snickered, while others sat quietly with their arms folded across their chest. Five young sat together and occasionally whispered back and forth.

"My father left me when I was 2 years old, and my mother left me when I was 4. I grew up with my grandmother most of my life. She was like a role model. My mother was never there for me," said Clive Bosman, 23, of Westbury, a township outside of Johannesburg. "But I still love her irrespective of that. It hurts me to know that my parents don't even care about me. These things also drive me to a certain point in my life where I feel like I'm on my own. I'm with my granny, she's getting old and I don't have a job yet. I don't have a sense of direction."

Young people "at risk" will find the answers to most of their problems within themselves. Learning to take responsibility for their own lives is lesson one.

"If it's a skill, they could learn it," Steyn said. "If it's an attitude, it's up to them."

First-time mother of a 20 month-old, Claudia May, 21, of Johannesburg said the camp made her realize that having a good attitude is key for successful parenting.

"My mother took care of my responsibilities, and that made life so easy for me. I never knew that I had to go out in life and face the reality that I can't depend on family and friends," she said. "It's my responsibility to look after my child, and I must do what's right for me."

Although her attitude and outlook on life are slowly beginning to change, May can't help but think about the setbacks she's experienced because of her past decisions.

"I had my baby, and I thought it would be hard for me to go back school," she said. Turning down her parents' offer to look after her son while she went to school, May decided not to return. "I never realized that my family really loved me by sending me to school and giving me a second chance. I never took that chance."

About 18 percent of South Africa's black youth aged 20 to 24 have never attended school, and 45 percent of those who do attend only reach high school, according to the South African Police Services crime bulletin.

The lack of national youth programs and the uncertainty of consistent donors for community programs are two reasons youth aren't getting help faster, said Ted Leggett, a researcher at the University of Natal's Center for Social Development Studies.

"Organizations struggle to keep afloat and are regionally situated," he said. "You would need a Glen in every poor township," and that's just in order to band-aid a bleeding situation.

Youth For Christ, in Johannesburg, is another one of the few organizations trying to heal and help South Africa's youth. The agency established "Amakhaya," ("homes for the homeless" in Zulu), which houses about three dozen street kids. Its job creation program, Zakheni, placed 43 percent of its 196 participants in 1998.

"When working with young people we don't aim to look at one aspect of the child," said Nicki Bosman, Youth for Christ's development manager. "We try and work with the whole person to meet all their needs. We cater to the need for education, shelter, food, clothing, as well as emotional and spiritual needs."

Youth for Christ reaches juveniles as they sit in prison awaiting trial. Prison workers spend maybe just say six hours a week teaching young people about honesty and self-discipline through activities. The workers leave them with a sense of self-worth, Bosman said.

"The idea really is to keep unsentenced kids out of prison and out of trouble," said Conrad Groenwald, who heads social services at Johannesburg Prison and oversees the Youth For Christ prison program. The prison is overpopulated and operates with a limited amount of staff and money, he said, making it difficult to treat sentenced juveniles in a child-friendly way.

"It's an extremely worrying situation," he said.

Many of the youth serving time in prison have committed violent crimes, such as rape, murder, and possession of illegal firearms. For some offenders, the opportunity to participate in a diversion project came too late. Sentenced juveniles must then find ways to cope with the poor living, sleeping and eating conditions of prison life.

Inside Johannesburg Prison, a dark, cold and cave-like place, youths are held in

Marcel Huston in his black tank top and blue pants has a little fun of his own at the Wilgespruit Community Center, while his peers enjoy a piggy back ride activity. Photo by Kamika Dunlap. |

dormitory-like cells with bunk beds. As many as 60 kids are packed into cells allotted to hold 36. The air is hot and filled with the stench of human excrement. Young people sit on the grimy, urine-soaked prison floors, scarfing down their bowl of bland porridge, a piece of bread and a cup of milk for lunch. For one hour each day they are taken out to a small courtyard for recreational time.

Houston is fortunate. He has never been to prison. After his camp experience he feels better prepared to guard against becoming a victim or perpetrator of crime in his neighborhood.

"Everyday I ask God to let me see the next day," he said.