Community

Justice

A muslim group turns to violence to fight gangs in the Cape Flats.

By Julia Roller

CAPE TOWN, South Africa — Ebrahim Moosa was in the back room with his children when his house exploded on July 13, 1998. Luckily for Moosa and his family, the pipe bomb was in the front hall, and no one was hurt. But Moosa knew who was to blame — People Against Gangsterism and Drugs, a Muslim vigilante group that targeted him for speaking out against them. Although Moosa was at the time the head of Islamic studies at the University of Cape Town and had just received the prestigious Ford Foundation Grant, he knew that they would come after him again. So he left his job and his home and fled with his family to the United States less than a month after the bombing.

PAGAD and its alleged escapades have captured the headlines in South Africa many times in the four years since its inception. Its members describe PAGAD as a social organization working to rid South Africa of crime; police and other observers see it as a vigilante group that now terrorizes the neighborhoods it once set out to rescue. The only consensus South Africans can reach about PAGAD is that it started out as a good idea. To understand why it began and how it evolved, one must first turn to the Cape Town neighborhoods where it began.

A small child stands on a corner, twirling a homemade toy: a piece of string with a rock tied to the end. Behind him, houses huddle close together, their foundations sliding along the sandy ground. The windowless home in front of which he is standing belongs to a known drug dealer, clearly identifiable by the brick surrounding wall and black security gates. In Mitchell's Plain, this crowded neighborhood in the Cape Flats, jobs and schools are scarce, drugs and guns plentiful.

Each church elicits memories of a gangster funeral, each street the memorial of some innocent caught in the crossfire. This is the landscape of the Cape Flats, the troubled flatlands outside the beautiful sea and slope of Cape Town. The Cape Flats are the home of the coloured or mixed-race class, the social misfits of Apartheid. Either products of black and white unions or descendants of light-skinned African tribes like the Khosa, they were light enough to avoid designation as black Africans. But this didn't make their lives easy — coloured people lived a precarious existence, caught between the two extremes of white and black. They are still caught, trapped in the cycle of poverty and despair unrelieved by the end of Apartheid six years ago. In the Cape Flats, the average family size is nine, and more than 2/3 of these families live in poverty. They are counted lucky to have electricity and running water.

In a place like Mitchell's Plain which offers its 1.5 million residents no schools, a single movie theater and two shopping centers, there is little to do but sit around, have a drink, trade some gossip, smoke some crack, and rob your neighbor. Gang violence was an inevitability, and the end of Apartheid only worsened the situation. When South Africa transitioned from a police state to a fledgling democracy, these gangs took advantage of the less visible police to openly peddle drugs and extort "protection fees" from innocent citizens.

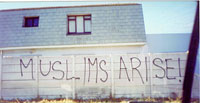

|

Muslim graffiti decorates a wall near the Gatesville Mosque where PAGAD's first meeting was held. Photo by Julia Roller. |

"It's very easy to be drawn into a gang," said Captain Desmond Laing of the Mitchell's Plain police. "The problem is people are very poor, and drug addiction is very high. If you don't have money, and a gangster comes to you and says 'Here's some money. I'll pay your water and electric and food and by exchange, I'll leave packets for you,' you're going to do it. They store their firearms and drugs at innocent people's houses. Everybody wants Levi's jeans."

And the attraction of gang life is more than the siren song of Levi's and FUBU jeans. For a society heavily influenced by American rap culture, it's cool to be in a gang. The heroes of the Cape Flats gangsters are evident in the omnipresent graffiti: gang names like Ugly Americans, Young Americans and Sisco Yakkies decorate any available space. On the sides of one Mitchell's Plain apartment building are two huge murals of American rap icons Snoop Doggy Dogg and Tupac Shakur, smirking down upon these sorry stomping grounds.

Although there may be a known drug dealer on virtually each corner of the Cape Flats, there is also a mosque. Along with being predominantly poor and coloured, the residents of Cape Flats are also 80 percent Muslim. To them, the drugs and alcohol peddled by local gangsters were particularly offensive since Islam forbids the use of intoxicants.

Frustration with local gangs and the inability of police to stop them led many of these Muslims to gather in the local Gatesville Mosque in 1996 and spontaneously create what was later named PAGAD, People Against Gangsterism and Drugs. At first, the community response was overwhelmingly positive.

"Organized crime has taken off as if it was going out of fashion," said Moosa. "Everyone in Cape Town lives in fear of wanton crime, and PAGAD was seeming to fight it."

"It was becoming so bad that people were being killed," said Ebrahim Francis, one of the early founders of PAGAD. "People felt the answer to the drug problem was community involvement. We didn't have to ask people to support us; they came out in the hundreds."

Starting with marches and protests, the situation quickly became bloody. In 1996, members of PAGAD marched to the home of Rashied Staggie, the notorious leader of the Hard Living gang. Thousands of fed-up community members met at the Gatesville Mosque and drove to his Woodstock neighborhood. They then marched to Staggie's home to demand that he stop dealing. But according to the police, once they got to his home, PAGAD members started firing on the house. Shocked, the marchers watched as Staggie returned fire and then came outside to face the protesters. He was shot seventeen (?) times, and then a man came to the front with a plastic bag. When he poured what turned out to be gasoline on Staggie and set him alight, most of the working-class marchers fled in horror.

"That was a spur-of-the-moment march which didn't have anything to do with those who founded PAGAD," protested Francis, but it was a clear turning point in the history of the group. What started as a neighborhood watch-style anti-gangsterism group had now decided to fight violence with violence.

"PAGAD has just become another gang," said Ebrahim Moosa, former head of Islamic studies at the University of Cape Town. "It has completely intimidated the Muslim community. Some pay protection money to PAGAD."

PAGAD has been accused of being more than a Muslim gang. Members of the group have been accused of pipe-bombing not only the homes of gangsters, but also public places like Planet Hollywood, pizzerias, clubs and police stations. Many believe that PAGAD is a political group, a front for Muslim groups like Islamic Unity Convention and Qibla, both led by Muslim activist Achmet Cassiem. Cassiem was an member of the Pan-Africanist Congress, a rival of the African National Congress, the current majority party.

"PAGAD emerges from an ideological base which rejected the new South Africa out of hand. [The Pan-Africanist Congress and those to the left]," said Rashied Omar, leader of the Claremont Mosque. "A lot of what they're saying I can agree with. The situation is not ideal because South Africa was the product of a compromise."

In the past, Cassiem has stated that his goal is a Muslim state, which seems a ridiculous objective since South Africa is about 1.39 percent Muslim. But the Qibla slogan, One Solution, Islamic Revolution, has been seen flying at PAGAD marches. Whether the members of PAGAD want to overthrow the government is contested, but it is clear that the group feels targeted by the state.

"[The state's] been using every means at their disposal," said Abiedah Roberts, national secretary of PAGAD. "They've been using the media. They always choose negative comments from the community. The news have been used to sideline PAGAD. .. They see us as political enemies. We are not a political group; we have a political understanding but we don't have political aspirations."

Members of PAGAD deny any connection to Cassiem, Qibla or the Islamic Unity Convention. "PAGAD is a community of believers," said Ebrahim Francis. "They come from all organizations and they come as individuals. PAGAD has no links whatsoever with any other organizations. No other person from another group has influence, but PAGAD will support anyone who wants to make a contribution to the fight against gangsters."

PAGAD purports to be a social organization promoting spiritual programs to fight drug addiction. In 1998, PAGAD opened a drug treatment center to much fanfare, but little has been heard about the center since then. Whether or not PAGAD is responsible for all the bombings in which the group is suspected, it is clear the group has turned to violence rather than spirituality.

"You don't live in a township," said Francis, gesturing to the split lip he received in a recent altercation. "You're window shopping. When you live in a society like that, you need to take drastic action. I think innocent people should be intimidating gangsters."

"It's not violence, it's protecting each other," agrees Abiedah Roberts.

This attitude is an undeniably Muslim one. Although the members of PAGAD say it is not a Muslim organization, its Western Cape membership is at least 95 percent Muslim. They mobilize in mosques, sing Islamic songs and wave Islamic slogans at their rallies.

Francis calls Christian attitudes of turning the other cheek "pie in the sky stuff." "Any religion which doesn't oppose oppression isn't complete," he said. "We need to do physical, pragmatic things. This love all people thing can never be enough."

|

Muslim parents interested in protecting their children from the Cape Flats gangs have allegedly turned to violence as members of the vigilante group PAGAD. Photo by Mimi Chakarova. |

"Islam certainly seemed to find justification for violence more easily than Christianity," said Rashied Omar, leader of Cape Town's Claremont Mosque.

PAGAD supports violence if it helps the fight against gangsterism and drugs, said Francis. "We want to see society rid of these evils," he said. "We don't want to see them marginalized; we want to see them eradicated."

Despite this support of violence, Francis argues that it is ludicrous that his organization working for social good has become the usual suspect for every violent act in Cape Town.

"If a cat runs across the street, oh, that must be PAGAD," he said sarcastically.

Francis argues that police have time to hang out in front of Gatesville Mosque while they pray, but they don't seem to have the manpower to arrest gangsters. "They've locked us up, beat us, infiltrated us," he said. The state was quite busy."

Francis and company have stories about their PAGAD brothers being constantly harassed without provocation. They claim one man was arrested because a bomb was found four doors away from his residence, and others are subjected to searches so complete that no vacuum bag is left unemptied. 41 members of the organization are now in jail, causing PAGAD to add prison ministry to its list of social causes.

"It's reminiscent of apartheid," said PAGAD's national secretary Abiedah Roberts.

PAGAD is not alone in its distrust of the police. "Police are known for corruption," said Moosa. "The ANC's problem is that they haven't been able to restore credibility to the police."

Police say that the problem is that the members of PAGAD are taking the law into their own hands. The police are also members of the community in which they serve, and they have the same goals as PAGAD.

"We are also people against gangsterism and drugs, but we stay within the parameters of the law," said Inspector Kevin Daniels of the Mitchell Plains crime prevention unit.

Daniels has been policing for 15 years, doing what he calls the "donkey work" in the neighborhoods of the Cape Flats. Gang-related incidents are the police force's main priority, he says. But there is so much violence that it is difficult for his team to so much but keep hauling in the little people.

"Yesterday we recovered five guns," he said in his slow and practiced English. "That's just a typical day, unfortunately." Behind him are two "Rasta", young men with long black dreadlocks arrested for firearm possession. They wear no handcuffs and wander around the dingy back room of the police station chatting in Zulu to the policemen who arrested them, avoiding the crumpled cigarette packs on the floor.

Daniels and his team know that the young men and women they bring in for weapons and drugs are just symptoms of the problem. They speak of treating them fairly and with dignity, but their cells are still crowded rooms with hard stone floors and no beds or pillows. Some of the people in the holding cells are gang members, others are associated with PAGAD. Men like Daniels have put 41 members of the group behind bars, but he still sympathizes with their motives.

"My view is that their principles are great," said Daniels. "But there are people who have overstepped their bounds and are using PAGAD for their own means — power in their community."

The police have a strangely amiable relationship with the community. Daniels and the rest of his team put in 16-17 hour days up to five times a week. Most of their shift is composed of driving around Mitchell's Plain in highly visible police vehicles, trying to offer a sense of order. On this Saturday night, they drive with two other vehicles, leaping out periodically to pat down people who look suspicious — anyone whom they have arrested before or who is loitering outside or on the way to a dealer's home. Strangely, the people who they check for weapons and drugs don't seem to mind. They submit patiently and exchange greetings and handshakes afterwards.

One man approaches the vehicle to give Daniels an enthusiastic handshake. Daniels explains that he met him a few days before when he arrested him for possession of two guns and 100 narcotic pills called "mastras." The members of the community, most of whom seem to be spending Saturday night strolling the crowded streets, all wave and call hellos to the police.

It is the members of PAGAD rather than the gangs who are now intimidating this community, says Mitchell's Plain Police Captain Desmond Laing. The large map behind his desk detailing dozens of pipe-bombings attributed to PAGAD shows how much of his time he has dedicated to capturing members of the group. Even Laing's Belleville house has been broken into, and he alleges that PAGAD members were seen around his house at the time.

According to Laing, PAGAD has sponsored six or seven marches in Mitchell's Plain, many of which have ended in violence. The group was also fingered for numerous deaths such as that of Young Cisco Yakkies gang leader Glen Kahn. In 1998, the police arrested 11 march leaders for firearms possession and intimidation during a march in which a drug dealer was shot. That was the first breakthrough, said Laing. Up to that point, police and community members alike were so intimidated by PAGAD that they feared testifying.

"My people were very reluctant to testify," said Laing. "If the police weren't willing to protect me in Bellville, how could they protect them in Mitchell's Plain?"

But at this point, most of the leaders of PAGAD are in jail, and magically, the bombings have stopped.

"I can testify to about 40 charges against them," said Laing. "The evidence against them is waterproof. There's no way they'll be acquitted."

The bad press and allegations of violence have taken their toll on PAGAD members outside prison. "PAGAD's numbers have plummeted," said Moosa. "They can barely raise 50 to 70 members. When the prisoners tried to go on a hunger strike, they had to abandon it for lack of public interest."

"I personally believe that PAGAD's backbone has been broken," said Laing.

But what does this mean for Mitchell's Plain and the other neighborhoods of Cape Flats?

"Now we're back to square one," said Laing. "The gangsters are joining together again." The Mitchell's Plain station has been holding meetings to attempt to negotiate peace between the Americans gang and the Cisco Yakkies at the same time they were putting members of PAGAD behind bars.

But there is no doubt that PAGAD has left its mark on the community. "Ten, twenty years ago gangsters were the kings," said Abiedah Roberts. "They could walk in your house and nobody could do a thing. PAGAD is changing all that. It's not fear of gangsters now; it's fear for the community."

And will the community be better off without PAGAD? "Just imagine Cape Town without PAGAD," said Omar. "They've wiped out more than half of the big [gangsters]."