Running Against All Odds

By Jenica Dover

THAMBAZIMBI, South Africa — Having finished his mid day relaxation of listening to music — one of the few stimuli available on the isolated Gannahoek Game Park near the Botswana border — Josiah Thugwane, 1996 Olympic marathon winner, suddenly emerged from the clammy, sweat-smelling white and red-roofed cottage bearing his soles.

Standing amid a heap of soiled Nike sneakers and a moist towel on the rutted porch, Josiah tucked his shirt into his short black and white striped running shorts. The elastic snapped back against his diminutive body.

He adjusted the watch on his tiny wrist and positioned his fiery red-orange tinted athletic eyeglasses on his face, shielding his eyes from the intense sun now piercing through the spray of clouds. A yellow butterfly whisked across his chest. The squalls of rain had dissipated, leaving behind a saturated ground and a new fresh air.

He stepped down from the entryway, passing a few dogs milling around keeping watch for trespassers and propped his extended arm on a concrete wall and started stretching and pulling each ligament.

Everything was still. Except for the occasional rustle of the afternoon wind in the foliage of the trees and the sounds of Luther Vandross' "Secret Lover," the sultry rhythm and blues song lingering from the CD player inside; a tranquil quietness enveloped the farm, three hours north of Johannesburg. Josiah, the first black gold medallist in South Africa's 92-year association with the Games, was preparing for his forty minute run with his black running partner, Brian Zondi, 25.

As he ran towards the narrow entrance of the farm passing a few ostriches and deer on the way, Josiah's poised body exuded the same deep passion that propelled him across the finish line in Atlanta.

|

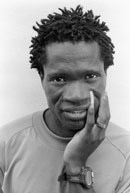

Josiah Thugwane sets the pace during a forty-minute afternoon run with running partner, Brian Zondi, along the red dirt road leading to Gannahoek Game Farm where Thugwane trains. Photo by Mimi Chakarova. |

He then turned left out of the farm and onto the dirt road, thrusting each leg into motion. His legs hit the surface with agility and grace, his buttocks tightened and the hamstrings and quadriceps in his thighs stiffened when he lunged forward. Behind him lay an impenetrable mass of bush, and a distant chain of mountain slopes dotted with deep green grass.

Several years after his historic finish in Centennial Olympic Stadium, Josiah, who was unknown before the Olympics, is training for the London Marathon and continues to pave the way for fellow black South African runners.

. . .

South Africa's all-white athletic teams, once banned and reviled for 32 years by most of the world during apartheid, are making their mark on the international stage. And after many years of exclusion from national competition incited by apartheid's policy, black athletes like Josiah are well on their way to being respected in the unifying sport of running. Post-apartheid has ushered in a new wave of African marathon runners in this epoch of global competition, who run in search of honor and pride for their native country. "I won the medal for all the people of South Africa and especially for my president, Nelson Mandela, who made it possible for us to be part of the international community," Josiah said at a news conference in Johannesburg, days after he received the gold medal four years ago.

There's a new South Africa now, a new president and a new batch of black runners exploding onto the roads, making their mark nationally and internationally in long-distance running, a sport that Kenyans have dominated for so many years.

"If you win medals, people take notice and that is what our runners are doing," said Richard Stander, national development manager of athletes and coaches for Athletics South Africa. "Our marathon athletes are winning medals where it counts."

"Josiah Thugwane is the national hero in this country over and over," he said. "And it is for a good reason. This country has been destabilized in the past. People do not have the same kind of backgrounds and to focus people on the advancement of sport is ideal."

Josiah's success has sparked a running boom among black South Africans and catapulted marathoners to the forefront. The country's two esteemed races, the Comrades Marathon and the Two Oceans Marathon, have seen an increase in the number of entrants — the majority is African. The Comrades marathon boasts over 16,000 participants.

But it is Josiah's humility that has captured the hearts of many. In 1997, Josiah forfeited his spot in the world marathon championships to give another runner the opportunity to compete internationally. He also spent some of his prize money from a third-place London Marathon finish on buying running shoes to dispense to people in townships.

"We are proud of anyone who achieves and does well," said Alan Smith, 44, a colored marathon runner from Johannesburg. "Even if it is a local schoolboy competing, everyone encourages that person. It is the talk among the community."

"Josiah has been a great inspiration and example of how running can get you through," said Smith, who has been running since he was a child — running from the law and gangsters for most of his life. "People see what he used to be and now today he is a wealthy man."

. . .

On the road leading into the hills and at a moderate but sure pace, Josiah's run looked effortless and easy as he concentrated on hopefully one day repeating the miracle of his life — winning the gold medal. At 28, he looked aged, unassuming and at times as if he was carrying the whole country on his shoulders.

For Josiah, with his crop of short dreadlocks and 5-foot-3-inch, 99-pound frame - a small size for a marathon runner — it's been a long, arduous road coming. And running has been his solace. He vigorously whipped his arms back and forth and kicked up the red earth as he ran hard and fast down the winding road through the high-altitude terrain, 1,800 meters above sea level.

His life hasn't always been as easy as the steady strides he maneuvers while running the gravel road, thirty miles away from the nearest store. Josiah's tiny stature and gentle voice speak little to the paramount hardships he endured to become one of South Africa's premiere marathon runners. It was just three years ago that Josiah learned how to read, write and speak English in one year.

"I felt lucky to learn how to read and write," said Josiah, who is a member of the Ndebele tribe and whose native language is Zulu. And after the tutelage ended in 1997, Josiah was still determined to learn more. "If I get the chance, I will try to help myself." His wife, Zodwa, continues to assist him with his English.

His resilient attitude helped him to face the harsh realities of growing up during apartheid. He was born into rural poverty and when he was a child, his parents, who made $20 a month as farm laborers, split up. His mother abandoned him, forcing him to live with his grandparents in a rural shack and from there on a farm in the Mpumalanga province. A white man who occasionally beat Josiah when he didn't tend to the cattle owned the farm.

"Before running the family was struggling," he said with understatement. "This was during apartheid, it was very difficult to work on the farm. At least it is better now where everything has changed. I told myself there was no way to stay on the farm to support the family. If they stayed on the farm everything would be difficult, it is not like staying in the village."

At that time his only sport was soccer, as was the case with most black male South Africans, which he played with the other farm boys as an aggressive striker. He had dreams of one day turning professional. During the time on the farm he never got the time to practice for running. Instead Josiah watched a television program featuring the South African half-marathon runners Mathews Temane and Xolile Yawa and envisioned his way out of poverty.

"I looked on the TV and I saw people running and I said that could be me, so in 1988, I started running," he said. "Someone saw me running and said that if you start running (competitively) it will be better."

It didn't get better overnight, but Josiah set out to do something about his living conditions. With no education in Zulu, running took him to his first half-marathon at the age of 17 — he won it by borrowing a pair of shoes from his friend and brought home $8 — and to a host of prestigious national and international marathons, including Soweto, a local township; London, New York and Japan.

Eventually he took a job as a cook and later became a sweeper at the Koornfontein Blinkpan coal mine in Middleburg. He remained there until the Atlanta Olympics in 1996, living with his growing family in a small zinc shack with no electricity and no running water. To supplement his $200 a month mine job, Josiah, like many black South African runners, ran races almost every week to hopefully earn an extra $50 to $200 in prize money.

"To start running and doing well gave me a chance to help the family and me as well," he said. "Even now I support them through running."

It is from the mines that Josiah materialized into a threat. His combination of natural speed and stamina and fearless dedication to training brought him several victories to earn him a place on South Africa's Olympic squad.

"I started running 5K's and 10K's and was running fast because I played soccer and used my speed as a soccer player to run fast in shorter distances," Josiah said. "There were many people running fast and I told myself that I should run marathons. I started training for marathons and it was good running marathons. I knew this was my distance and worked my way up."

From the squalor of the farm and mines to elite marathon running, Josiah ran from obscurity — having no manager or shoe contract before the Olympics — to become his country's leading distance man. Along with his friends Lawrence Peu, who is Josiah's running mate on the farm, and Gert Thys, Josiah joined the Olympic squad and was trained by Jacques Malan. Malan, a white coach, sent the trio to the Gannahoek Game Park before the big race for a 12-week eat-sleep-run routine that was only broken by swimming, television and a weekly drive to the nearest shop.

Malan, who started coaching Josiah a couple of months before the Olympics, said that even during the monastic seclusion training, Josiah had tremendous discipline. He said he never had to check whether Josiah was doing the work.

Josiah's immense self-drive and discipline proved to be successful when he entered the Olympic stadium to win the closest ever Olympic marathon, by three seconds, in a time of 2:12:36. It was an electric moment in South African history, a black man entering the Olympic stadium in Atlanta, leading by a hair all other front runners.

He crossed the finish line a moment later and instantly became a galvanizing symbol of a new South Africa. After his win, he was greeted by Mandela in South Africa and was featured in a ticker-tape parade in downtown Johannesburg — here, was a hero to marvel over. Four years later, Josiah is still as popular as ever in South Africa.

"I've won a lot of races before, but they did not feel like the Olympics," Josiah said, glowing at the memory. "Many people surprised me when I came back, there were many interviews for TV and many people wanted to see me, but for me I just wanted to run good. The Olympics is special, it is not like any other race especially when the whole country is watching. I wanted to run for the country."

"I stay here in South Africa, I was born here in South Africa, and I will try to do well for my country," he continued. "Every time I run internationally, I try to look nice for my country, not for me only but for the people here in South Africa." He and many other runners have made their sneaker marks on the world stage. After the 1996 Olympics, Josiah ran in the prestigious Fukuoka Marathon in Japan, when he trounced a top-class field, including Spain's world champion Abel Anton, with a time of 2:07:28 — only 38 seconds off Belayneh Dinsamo's 10-year old world record. Next, he overcame wet, blustery conditions to beat Kenya's John Matui and Spain's Martin Fiz to win the world's largest-field half-marathon, the Great Northern Run, in Newcastle, England in a time of 62 minutes 32 seconds.

Another shot came in the 1998 London Marathon, but he had to drop out of the race halfway after sustaining an ankle injury through jumping off the pavement to avoid a wheelchair athlete. There are times when the marathoner has to hide the disappointment, go inside himself and regroup during the lonely times when he is running and grit his teeth to discover in his own way the need to keep fighting. Josiah, always indefatigable, did just that and bounced back.

"I didn't feel happy when I didn't finish the London Marathon," he said. "Sometimes I get problems during the race and can't finish. I just tell myself that I will try the next time. The London Marathon is every year, it is still coming. If I get the chance to go, I will go. Last year, I had the same problem and had the flu and didn't finish the race again. But I tell myself, it is okay. It wasn't my day today."

. . .

On this secluded farm, Josiah has been training and waiting to find out if he will qualify for the 2000 Olympics in Sydney. He lives, trains and runs by three precepts: passion, hard work and determination and the "Olympics is the fast road that keeps [him] up."

Though money has altered his life significantly — Josiah was able to quit his job at the mine to run professionally, and use the prize money to buy a palatial mansion in a suburb of Johannesburg, an Isuzu Rodeo 4x4 and install an extensive security system — ultimately it is not about the fame and fortune.

Even with all of the accolades, Josiah shies away from the media and celebratory attention. The bedroom walls in the training farm are bare and in his house in Johannesburg few plaques or awards garner the house. A few trophies sit on a bookshelf, but his prized gold medal is locked up in a safe in the bank. After his win, Josiah had been the victim of a few robbery attempts and months before he went off to Atlanta, a bullet grazed his chin when two gunmen tried to hijack his new pickup truck.

As Josiah glides his long pinky fingernail — he started growing it after he won the Olympics, though it broke off once — across the deep welt on his chin, his legs are stretched out on the log couch in the sparsely furnished cottage and his head is perched atop his bent arm.

Torn red curtains with frayed edges loosely dangle from the curtain rod in the meager cottage, fenced off from the expansive countryside and one clothesline hangs in the back. Josiah, a subdued man, was attracted to this idyllic haven, nestled in an indigenous tranquil environment. Unlike other training camps, such as Max Africa in Port Elizabeth, South Africa, where runners are now training for the Olympics, it doesn't boast of state-of-the-art facilities, full-time chefs, masseuses, and recreation facilities. His life is simple: running, food and sleep.

"Training here is fine for me. I cook for myself, special food for me, meat and porridge, chicken or beef, and sometimes rice and I eat that every day," Josiah said, describing his daily regimen. "In the morning I eat bread and drink tea. Especially for long runs and distance running, I eat more porridge and more meat, and for me this works well. I drink lots of water, orange juice and sometimes Coca-Cola."

"It is a good safe place for training and I am happy here, nobody to disturb you. I can train, eat, sleep and just relax. But if I train in the city, many people will come up to me and say 'Oh Josiah, wait, wait, wait.' In Thambazimbi, there are not too many people who know me." He has visited his wife and three kids in Johannesburg every two weeks during this nine-week training period.

Josiah also trains here because the land is flat and the course in London is too. He trains on the same conditions that he will run in an upcoming marathon and trains with one goal in mind.

"When I go into competition, I am happy if I start and finish the race," he said. "Never mind about winning. I don't mind winning, but I am happy if I start and finish the race. While running a race, I don't think of anything, I just tell myself I'm training now for this race and will be happy when I finish."

Josiah also is quite happy when he works with kids in the city. He started a soccer team in Johannesburg and is encouraging kids to run in a country where apartheid left only one running track for all of black South Africa. "Many kids will come up to me and say Josiah I am going start running, but they just want to get the shoes. I tell them, 'don't do it like this, that is running just to get the shoes.' They must struggle first before they get the shoes."

"In South Africa, many kids don't stay at home they stay in the streets, but if one or two of the kids from the streets say that I want to start running and I want to try to be a superstar like Josiah, I feel happy. These kids might be coming from the streets, but they want to change and start running."

Although Josiah's aim is to win all the big races before retiring, his altruism will carry over when he finishes his professional career.

"I still want to win the London Marathon and the New York Marathon.," he said. "If I win these two races, then I will retire. And of course when I retire I will help the young coming up, and help them with what to do and teach them about running. I know there are many struggling here in South Africa, especially for the sponsorship. It is not easy to get the sponsorship, even for the good athletes."

Even for an elite athlete like Josiah, when his Nike contract, which pays him $25,000 a year, terminates at the end of this year, he fears he will be looking for sponsors and sponsorship is synonymous with great performances. Josiah always is worried about supporting his family.

"As a professional runner, it is difficult to support myself because I am not getting the sponsorship in South Africa like I used to," Josiah said. "Maybe a thousand rand or two thousand rand ($150 - $300) here and there or nothing. This year the sponsorship with Nike is finished, and once it is over, I start struggling again."

He laughed — just another hurdle that Josiah must overcome. "If I am not running good enough in London, or if I don't qualify for the Olympics, then I start struggling again. But I will try to find a way to help me and my family."

Josiah said he thinks of the road as his loving friend, and his friend should give him another shot at gold.