Founded in 1933 by Slim Jenkins, Slim Jenkins’ Place began as little more than a corner juke joint. Under Jenkins’ disciplined hand, it soon became the premiere club in 7th Street’s blues and jazz orbit, widely recognized as West Oakland’s favorite nightspot. Jenkins wanted to create a place where clientele of all races could listen to music, dance, and enjoy themselves. And enjoy they did.

Observers recall lines around the block, and taxis coming and going, filled with people heading to Slim’s to see the headliners. The neon flashed above them and the streets sparkled under their feet. For more than two decades, through the thirties, forties and beyond, the club featured star players to rapt audiences. The setting was elegant, with tables covered in white tablecloths and candles flickering in the dark. The musicians were illustrious. Among them; Louis Jordan, B.B. King, Charles Brown, The Ink Spots, Ivory Joe Hunter, Duke Ellington, Sarah Vaughan, and many others.

On any given night visitors could find proprietor Jenkins standing in his club, a cigar in his mouth, his signature white hair cropped close, taking in the splendor of his dream-come-true; aware that his club’s fame had spread beyond the bay to become “the most celebrated black nightclub on the West Coast.”

The club was also referred to as Jenkins’ Corner, or Slim Jenkins’ Supperclub. It was impressive enough to draw crowds and inspire other people’s dreams. Esther Mabry, one of Slims’ waitresses, opened her own restaurant, then a club, on 7th Street with Slim’s encouragement. Jenkins liked to nurture dreams. He promoted bands and musicians he liked. He helped make The Platters famous by changing their wardrobe and featuring them at the club.

Reportedly, Slim Jenkins didn’t mess around when it came to business. He insisted that the bands performing at the club behave professionally. According to James Moore, “Back then, people felt a responsibility for the music. That was reflected in how they dressed. They (the musicians) dressed out of respect for the art form.” Bob Geddins remembers that Slim didn’t even tolerate “scraggly” customers.

After more than two decades, the club maintained an impeccable reputation. When the club was razed in 1962 to make way for a gas station, (Jenkins never owned the land on which his club was built) and tried to move elsewhere, the city and police vouched for him. After a local church protested Jenkins’ attempt to move the club to their neighborhood, he settled instead on Broadway Street in Oakland, near Jack London Square. He operated the club until his death in 1967.

Slim Jenkins’ Place had many incarnations. From humble beginnings it grew to house a restaurant, banquet room, bar, liquor store and market. Jenkins was always renovating, expanding, and changing to meet the needs of the public, honor the music, and suit his personal style.

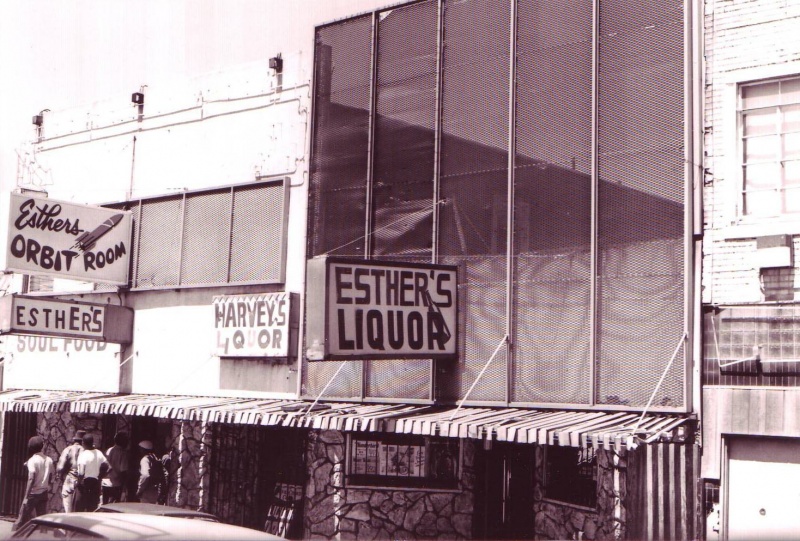

Club owner Esther Mabry once described 7th Street as “the only place anyone would ever want to go.” Esther’s Orbit Room was one of the reasons. Founded in the 1960s by Esther and her husband William, Esther’s Orbit Room was a nightclub, bar and restaurant. Though it didn’t feature some of the big names that headlined at neighboring Slim Jenkin’s Place, the Orbit Room had its own array of world-class acts. The club’s longevity was also impressive. It was the last holdout long after other 7th Street nightclubs and businesses went under or were snapped up by developers.

Club owner Esther Mabry once described 7th Street as “the only place anyone would ever want to go.” Esther’s Orbit Room was one of the reasons. Founded in the 1960s by Esther and her husband William, Esther’s Orbit Room was a nightclub, bar and restaurant. Though it didn’t feature some of the big names that headlined at neighboring Slim Jenkin’s Place, the Orbit Room had its own array of world-class acts. The club’s longevity was also impressive. It was the last holdout long after other 7th Street nightclubs and businesses went under or were snapped up by developers.