Balseros,

Cuba's last wave and its first immigrants

By

Archana Pyati

Researcher: Eddy Ramirez

They worked in an abandoned

house at the edge of Guayabal, a dusty hamlet about an hour's drive

from Havana. Slowly, they fit the wood and metal together to make a

vessel sturdy enough to hold six passengers. When it was ready a month

and a half later, they packed water, food and a few clothes for the

long journey ahead of them. They kissed Hany, their 5-year-old daughter

goodbye, and snapped a picture of her sleeping form, capturing the sheets

and blankets tossed this way and that by her small legs. Four hours

later, before the sun rose on August 21, 1994, Barbarita and Orlando

sailed to Miami.

| It wasn't

long before rumors spread: Orlando and Barbarita had died at sea. |

Orlando's sister, Miriam,

remembers standing waist-deep in the black, tranquil water to push them

off Playa Banes, a beach half an hour from Guayabal. The motor sounded

strong and the current was swift. She expected to hear from them in

Miami in a day, but to ensure their safe journey, she left the beach

that morning and walked six hours to pray at the church of Saint Lazarus

in El Rincón.

For 12 days, she heard nothing.

Guayabal is a town where gossip and hearsay proliferate, so it wasn't

long before rumors spread: Orlando and Barbarita had died at sea. "Those

days were black," she says, remembering one in which she waited

for a public phone and overheard two women telling stories of people

who had drowned in the Florida Straits. "I told them, do me a favor,

and shut up," she says. And then the call came. Her brother and

sister-in-law had been picked up at sea and taken the U.S. Naval Base

at Guantánamo Bay on the island's southeastern coast. Miriam,

too, could have climbed aboard that August morning. Does she regret

not getting on the boat? "Of course," she says, seven years

later. "But I saw the sea and I panicked. I didn't have the heart

to leave." After all, there was Hany, her 5-year-old niece, to

think about.

|

|

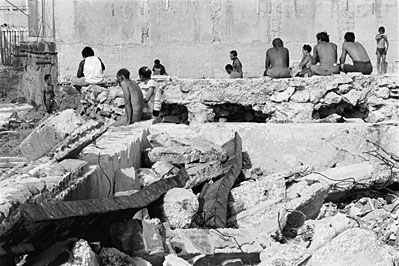

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

Overnight, Orlando and Barbarita

became balseros, or rafters, the generation of Cuban migrants who preferred

the risky venture across shark-infested waters to what they considered

an intolerable life in Cuba. They were among 33,000 Cubans who left

the coast that summer with the intention of starting a new life in the

United States. It would take them 18 months to finally make it to South

Florida. By the time they arrived, a radical shift in immigration policy

between the United States and Cuba had taken place. That August, President

Bill Clinton, concerned with South Florida's ability to absorb the new

immigrants, announced the reversal of a 35-year-old policy welcoming

Cubans unconditionally. No longer would the Coast Guard invite Cubans

aboard its boats to deliver them safely in the arms of Miami relatives.

Cubans had been jumping

on whatever would float in the forty years since the Revolution, but

their desperation to do so achieved new heights in 1994. The country

was in the throes of the so-called "special period," a time

of empty food pantries, high unemployment, and a full-blown economic

depression, brought on by the demise of the Soviet bloc. A few desperate

souls began taking drastic measures that summer, hijacking boats and

storming embassies for exit visas that summer. Riots broke out in Havana,

prompting Fidel Castro to throw up his hands and declare on national

television that the Cuban coast guard would "not obstruct any boat

from leaving Cuba."

Barbarita and Orlando had

had enough. They seized one of Castro's weakest moments in history to

leave. The family's car, motorcycle, and television had been taken away

from them by the police in Guayabal. The couple saved money to buy materials

for a boat, and in that sense, were among the lucky ones. Most balseros'

departures weren't that well-planned. Rafts were hastily cobbled together

from anything they could find: plywood, inner tubes, tires, styro-foam,

even doors. "They came in the most incredible contraptions,"

remembers one Miami social worker of that summer.

| Most

balseros' departures weren't that well-planned. Rafts were hastily

cobbled together from anything they could find: plywood, inner tubes,

tires, styro-foam, even doors. |

The balseros were the latest

wave in an exodus that is as old as the Revolution. Since Castro took

power, each wave has come to Miami with a different set of hopes and

fears. The first came to escape the political turmoil overtaking the

island. As members of the bourgeoisie, they feared for their bank accounts

as much as for their lives. The second wave began with a massive boat-lift

from the port of Camarioca, on the island's northeastern coast. Next

came Operation Peter Pan, an airlift of thousands of children sent to

the United States by their parents who didn't want their offspring to

be taught in Communist schools. For years after that, parents joined

their children under the Freedom Flights program, a series of chartered

flights to the U.S. that ultimately transported around 250,000 Cubans.

The third wave came during the Mariel boat-lift in 1980, when thousands

stormed the Peruvian Embassy seeking asylum, and thousands more were

picked up by their Miami relatives.

As early as 1980, the U.S.government's

attitude toward Cuban refugees was shifting from sympathy to tolerance.

The Mariel Cubans were considered more financial liabilities than political

refugees by Washington D.C. The terminology used to describe them was

also changing: they were lumped together with Haitian boat people and

labeled with the impersonal term, "entrants." Socio-economically,

the Mariel Cubans were poorer than their predecessors. Many of them

had criminal backgrounds, which eroded U.S. enthusiasm for Cuban migration

even further. If economic necessity motivated those who came during

Mariel, then such motivation was even stronger for the balsero generation.

They are, in a sense, the first generation of Cuban immigrants—a

word that Cuban exiles consider an insult. To be an immigrant implies

choice, which none in this generation feels they had when they fled

the island. In fact, many assumed they would return to Cuba only when

Castro fell.

The two terms, "immigrant,"

and "exile" are not mutually exclusive for Barbarita and others

belonging to the balsero generation. Unlike el exilio, this generation

has grown weary of politics, having come of age in a political culture,

where signs posted in public places remind the country's citizens that,

"en cada barrio, la Revolución," in every neighborhood,

the Revolution. Unlike those who came before them, the balseros do not

dream of dying in Cuba, nor have they packed their bags for an imminent

return. They are not plotting Castro's downfall, nor are they trying

to influence US foreign policy to the detriment of those who remain

on the island. Their attitude is more ambivalent, and less dismissive,

towards life back in Cuba. They are trying to make a life for themselves

in Miami, or like Barbarita, thinking about the child they left behind.

Barbarita petitioned for Hany's visa on July 18, 1997, the day after

she received her green card. Earlier this month, the child received

a visa from the U.S. Interests Section in Havana, but has yet to receive

her "tarjeta blanca," or white exit papers every Cuban leaving

the island must show the authorities. The Cuban authorities are notorious

for slowing this process, so no one knows exactly when Hany will be

reunified with her parents, no one knows.

| Barbarita

calls her situation a "reverse Elian" quandry. |

At least her case has made

its way through the clogged visa pipeline. In the past year, 628 petitions

filed by Cubans, who are either U.S. citizens or permanent residents,

on behalf of relatives still in Cuba were considered open cases. This

means they've been approved by the Immigration and Naturalization Service,

but await processing by the National Visa Center in New Hampshire. Of

those, 564 cases have been forwarded to the U.S. Interests Section in

Havana, which says nothing about how long it will actually take for

the visa-holders to make it to Miami.

Barbarita calls her situation

a "reverse Elian" quandry, referring to the Cuban six-year-old

whose separation and eventually reunification with his father, Juan

Miguel Gonzalez, in April, 2000, inspired massive protests by the Cuban-American

community in Miami. Unlike Juan Miguel, Barbarita doesn't have the Attorney

General hastening her reunification with Hany. For now, she waits in

the world the exiles built.

|

|

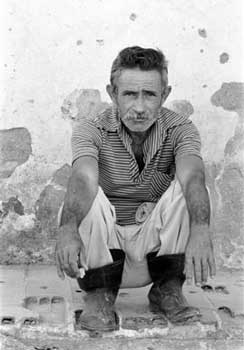

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

In any culture, the older

generation likes to set itself apart from those who follow. In the case

of the Cuban exiles, this differentiation is based on age as much as

ideology. It's not simply that the new arrivals are younger, poorer,

and less educated than those who came 40 years ago, it's that they "they've

been raised in a system where you don't have to fight," says Zoraida

Hernandez, a 68-year-old waitress. "It's a generation that doesn't

have love for work. Our generation…we loved work."

Yet all around us at Versailles,

a Little Havana institution on Calle Ocho are young men and a few women,

mostly under 30 and nearly all recent arrivals from Cuba, who are working

as waiters, bus-boys, cooks, and managers. Hernandez understands this

rhythms of this restaurant, since she has worked here since her own

arrival 30 years ago. Most of the employees, says the manager, work

ten to twelve hours a day. A few have had trouble adjusting to the work

schedule.

As a member of el exilio,

Zoraida's understanding of modern-day Cubans is frozen in time. Her

stereotypes are creations of nostalgia for la Cuba de ayer, the Cuba

of yesterday. Versailles, too, is filled with such sentiment, demonstrated

in artifacts all around the restaurant. For $20, one can buy a Havana

phone book from 1958, when the island's bourgeoisie was at the height

of its decadence and revolutionary forces were still training in the

jungles of the Sierra Maestra. Vintage issues of the influential literary

and political magazine, Bohemia, decorate the walls with cover illustration

of the hero both Communists and exiles can agree upoon: José

Martí, who threw off the yoke of Spanish imperialism. Montecristos

and Cohiba, brand-name cigars from the island, are for sale, and guava-filled

empanadas and other sugary pasteles sweat underneath display case lights.

Zoraida says "there is nothing like your homeland," and her

words come to life on a walk down Calle Ocho, known to English-speakers

in Miami as Southwest Eighth Street or the Tamiami Trail. I stroll past

the faded poster of lounge singer Benny Moré, past the cross-streets

which collapse Cuban history into a few blocks: Afro-Cuban leader Antonio

Maceo, another hero of Cuba's fight for independence from Spain, Brigade

2056 of the ill-fated Bay of Pigs invasion of 1961, and Brothers to

the Rescue, the even more tragic rescue squad who flew humanitarian

missions to rafters over the Florida Straits, and who were shot down

by Cuban MiGs in 1996.

Defenders and critics can

agree on one thing: the exile generation came to Miami and changed the

city forever. What used to be a sleepy beach resort in the early 20th

century became Latin America's northern-most financial and cultural

capital. Forty years after the revolution, you can see the community's

accomplishments. Over half of Miami businesses are owned by Cubans.

The mayors of both the city of Miami and Miami-Dade County are Cuban,

as is the publisher of Miami Herald, and its influential sister publication,

El Nuevo Herald.

| Defenders

and critics can agree on one thing: The exile generation came to

Miami and changed the city forever. |

Maximo Gomez Park is an

intimate corner of the exile's world, tucked away near a busy intersection

off Calle Ocho. Men gossip and sip sugary café cubano out of

small, thimble-sized paper cups. Underneath a blue and red awning, the

retirees play round after round of dominoes, clacking against the table

as cigar smoke fills the air. A "Summit of the Americas" mural

frames the domino players. Deposed leaders—Alberto Fujimori, Jean-Bertrand

Aristide—smile congenially under a cloudless, blue sky alongside

those in good standing—Ernesto Zedillo, Bill Clinton, Vicente Fox.

Conspicuously absent from

the painting, but ever present in the conversations of these men is

the man everyone loves to hate. Castro's name comes up when we talk

of the city's latest Cuban residents. "What comes from over there

was made by Fidel," says Amado Arregui, who arrived in Miami in

1948. Dressed in a khakhi windbreaker with milky-blue eyes that come

with age, Arregui leans on his cane and says he knows nothing about

the Revolution, except that "many of these kinds of people have

a shot of Communism in the arm," pointing an index finger toward

his arm as if it were a make-believe syringe. "These people"

means the balseros, and his analysis leaves little room for interpretation:

"There are a few good ones. But more bad people came with the good."

It is easy for men like

Arregui to draw such conclusions. Like many of the exile generation,

he is insulated from the world of recent Cuban immigrants. He spends

most of his day with other retirees, or with his children, who as Cuban-Americans,

make up the most educated and wealthiest Hispanic minority group in

the United States. His grasp of today's Cuba is tenuous. A "love-hate

relationship," is how Francisca Vigaud-Walsh, a 23-year-old, Cuban-American

social worker describes the relationship between the exiles and the

latest wave. "A lot of older Cuban Americans feel some kind of

resentment toward them because they withstood the politics of Cuba for

so long. There is a lot of suspicion about who they are," she says.

| "My

generation wasn't raised in politics. What I got to experience was

hunger, not politics," says Ivan Hernandez, a 35-year-old gas

station attendant. |

It doesn't help matters

that there is a spy trial underway in Miami at this time. Five men from

Cuba are standing trial for their role in La Red Avispa, the

Wasp Network, an elaborate espionage ring which allegedly sought to

infiltrate US military installations and Cuban exile groups. Another

domino player, 70-year-old Raul Guarino, clutches a copy of La Verdad,

one of countless newspapers written by and for the exile community.

The headline reads, El Asasino Castro Esta En La Mirilla—The Assassin

Castro is in the Peep-Hole. "They aren't like us," he says.

"We came here because of the repression, because of the ideas the

government supported. They have been educated in the system. They even

think it's good." Guarino sees a fundamental difference between

himself and the young Cubans he sees working at gas stations or grocery

store check-out lines. "They come here for economic reasons,"

he says with disdain. "They're looking for dollars."

They also don't carry the

political grudges of the exiles.As one recent arrival says, "My

generation wasn't raised in politics. What I got to experience was hunger,

not politics," says Ivan Hernandez, a 35-year-old gas station attendant.

Hernandez arrived his wife and daughter in Miami via Spain in January,

2000, just in time to experience the fury of Miami Cubans over the seizure

of little Elian Gonzalez by ATF agents in April, an episode which served

as a too eerie of a reminder of home. "I couldn't believe people

would get on the television and say the boy couldn't join his family

in Cuba," Ivan says. "Family comes before anything else. Above

politics."

Guarino had his own battles

to wage against public perception when he came during the Mariel boat-lift

in 1980. These refugees earned a bad reputation in part because Castro

allowed prisoners and the mentally ill to jump aboard boats leaving

Mariel. They were often referred to by the pejorative name, "Marielitos,

" by fellow Cubans in Miami. The Miami Herald issued this warning

to its readers as refugees began occupying tent cities all over South

Florida: "This is not the entrepreneurial class who came 15 years

ago. A Cuban ghetto might develop."

To everyone's surprise,

no ghetto emerged. The integrity of the Cuban enclave in Little Havana

remained in tact. The exiles complained about the Marielitos supposed

delinquency and laziness. In the end, no one suffered because of their

arrival, though the city's African-Americans felt their jobs had been

taken away from them by the new arrivals from Cuba. Guarino recalls

it was hard to find work. Then, like now, unemployment was high in Miami.

A brother-in-law found him a job at Howard Johnson's, which led to other

odd jobs in his 21 years in Miami. Others who came during Mariel weren't

so lucky. They were resettled elsewhere by social service and religious

organzations and were expelled from Little Havana's safety net. A few

moments later in our conversation, Guarino's sharp take on the balseros

softens: "A lot of people truly left [Cuba] because of the misery.

There's nothing wrong with that, because it's the truth."

As soon as it appears, his

sympathy for the new arrivals vanishes, and the conversation goes back

to his favorite topic, espionage. He, too, is a journalist and has been

hard at work on a commentary for exile radio station Radio Mambi about

how Cuban spies have even infiltrated Domino Park. And of course everyone

knows that spies are running Miami's biggest Latin grocery stores, he

says. Sedano's. Presidente. La Mia. He whispers the names as he scribbles

them in my notebook.

How can he tell who are

agents of Castro and who aren't?

"The Bible says, For

their deeds, I will know who they are," he says.

|

|

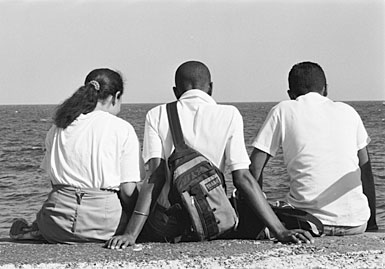

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

Far away from the paranoia

and political noise of Calle Ocho, Barbarita sits in the living room

of her Hialeah condo, painted a vanilla-colored stucco, ubiquitous in

South Florida. Hialeah has the look and feel of the suburbs with its

wide streets, strip malls, and fast-food outlets. The town has always

been known for horse racing, a sport which has attracted the likes of

the Kennedy clan, Harry Truman, and Winston Churchill. It is now home

to the one of the largest Cuban communities in Miami-Dade County.

The skeptics who were convinced

that the balseros would fail in the United States need look no further

than Barbarita and Orlando's home with its tasteful leather couches,

sparkling white kitchen with its well-stocked pantry, or to the parking

space outside where a new, bright-red, pick-up truck sits. The taste

of success has been bittersweet. "Everything my husband and I do

is thinking about her future," she says of Hany, her 12-year-old

daughter.

Barbarita works as a supervisor

at a men's apparel factory where she oversees about 30 employees. Orlando

owns his own auto repair and sales business, named after the daughter

he is unlikely to see anytime soon. He is considered persona non grata

in Cuba and isn't allowed to return. Hany is the missing chapter from

Barbarita's success story. Although she has seen her daughter twice

since she left in seven years ago, these visits were both too short,

and her daughter's absence looms over the Hialeah house. Even the kitchen

is decorated with a sunflower motif because, Barbarita says, "Hany

loves yellow."

Barbarita knew the trade-off

when she stepped into the boat that August morning. Though members of

the exile generation have long since claimed their relatives during

family reunification programs sponsored by the U.S. government, the

recent arrivals haven't been so lucky. Christine Reis, a Miami immigration

lawyer says the wait is typically four to six years for permanent residents

to successfully claim their children.

| "A

lot of people truly left [Cuba] because of the misery. There's nothing

wrong with that, because it's the truth." |

Meanwhile, she and Orlando

wait, working long hours to pass the time. The couple rarely goes out,

except to visit friends from Guayabal who have also made it to South

Florida. They have even decided against having another child, Barbarita

says, because they don't want Hany to feel like a forgotten child. For

now, she contents herself with watching her daughter grow up through

photographs. And they are everywhere.

Hanging above the television

set are two enlarged photos of Hany, one at seven, two years after they

left, with silk flowers in her hair, the other at age nine, looking

mature and solemn. On a glass table wedged between two leather sofas,

there are three more snapshots, and the drawer underneath the television

set overflows with pictures: Hany at dance recital; Hany at the quinceañera

party of Orlando's half-sister; Hany wearing an elegant dress made out

of crushed purple velvet. "She's growing up," Barbarita says,

cradling the picture of the 12-year-old. "She's already a lady."

We are sitting in Barbarita's

backyard, a tiny enclosed patio with a plastic table and a few chairs.

A girl's bike is parked off the one side, near the barbeque. It is a

gift from Uncle Pedro, Barbarita's older brother who came to the United

States in 1980 during the Mariel boatlift. Like her parents, the bike,

too, waits for Hany's arrival.

Barbarita is trying to recall

the lyrics of the song that gave her the idea for her daughter's name.

It's a song by the Cuban music group Las Javaloyas in which the phrase

te quiero, Honey, is repeated in the chorus. In the song, a man pines

for a long, lost love. Honey became Hany, and the girl cried with glee

every time she heard the song on the radio.

Orlando liked the name because

he wanted it be something "short and sweet," Barbarita says.

She and her husband have always been close, meeting each other as toddlers

and growing up across the street from each other in Guayabal. Pretty

soon, Barbarita was spending most of her time at the Azcuy house on

Avenida 79. They married in 1988, and Hany was born a year later.

Neither Barbarita or Orlando

were outspoken critics of the socialist system, but they made it known

they weren't true believers. They never went to communist youth group

meetings and never hung a Cuban flag from their house, a symbol of revolutionary

pride. In fact, their local branch of the Communist Party had been keeping

its eyes on the Azcuy family for some time. At one point, the family

owned a car, a motorcycle, and a television, unheard of in a country

where the average salary is 50 pesos, or $2, a month. The government

initiated what it called the plan maceta in the mid-1990s to crack down

on the noveau riche, the people who appeared to be acquiring material

goods in the aftermath of the dollar's legalization in 1993.

Literally, maceta

means "flower pot," and in this context, the word served as

a metaphor for someone capable of flourishing in a society that discouraged

the accumulation of wealth. In Guayabal, Orlando fixed cars, washing

machines or other outdated American appliances left over from the 1950s,

an era when Cuba was flush with American consumer goods. It wasn't long

before his own stash of dollars grew, setting him apart from his neighbors

and drawing the attention of authorities. "Imagine it," Barbarita

says of their departure. "We had no other choice."

|

A girl's

bike is parked off the one side, near the barbeque.

It

is a gift from Uncle Pedro, Barbarita's older brother who came

to the United States in 1980 during the Mariel boatlift.

Like

her parents, the bike, too, waits for Hany's arrival.

|

The couple left before Castro

began permitting Cubans to leave the island. They were at sea for less

than 48 hours when a huge Coast Guard ship appeared. The battleship

loomed before them, dwarfing their small boat. "When I saw that

huge ship, I felt scared, and I thought, oh my god, what did we do?"

Barbarita remembers. The Coast Guard ship stopped then, lifted them

aboard, and spray-painted their boat to show that its passengers had

already been picked up. The boat, which had taken them within thirty

miles of the Florida Keys, floated away into the horizon. She remembers

the boat as if it, too, was a family member. "We looked out on

our boat and all you saw was a little dot," she says. "It

looked so small."

During the next year and

a half at Guantánamo Naval Base, the U.S. government embarked

on a campaign to acculturate Cubans before they ever reached land. "Guantanamo

was like a school," she says. "It taught us what life was

like here." Her friends, fellow balseros, dispersed, some going

to Virginia, others to California. She keeps in touch with many of them.

"We were all like one big family," she says.

Once they got to Florida,

Barbarita and Orlando began a work schedule familiar to many immigrants.

Working two jobs, the couple slept four hours a night. Their day jobs

at the same factory where Barbarita still works began at seven in the

morning and ended at four in the afternoon. At five their shift as janitors

at a technical college in Broward County began, and they were in bed

well after midnight. Relatives in Hollywood, a suburb of Fort Lauderdale,

provided invaluable support in big and small ways, giving them a place

to stay and fixing their lunches before they left for work in the morning.

"We were so anxious to prosper," she says. "Here, at

least you are working towards a goal. In Cuba you're working towards

nothing."

Since her arrival, Barbarita

keeps one eye on the calendar, marking the the seven years and counting

she has been away from her daughter. She has tried her best to be a

good parent, in absentia. In the process, she has become a caretaker

for the rest of her family in Cuba, a role commonly assumed by those

who leave, says Antonio Aja, a sociologist at the University of Havana.

"In the 1990's, the family solution was for people to designate

a member of the family to leave," he says. "That relative

would be sent to the US…to establish himself and decide if he should

bring family or send money. It's a decision of how to save your family.

It's a question of how the family will float."

Hany isn't simply staying

afloat with the money her mother sends her. Her life has become a lavish

cruise filled with all the trappings of pre-teenage-hood: dolls, toys,

and clothes. She doesn't hesitate to tell her mother when she wants

a new outfit. In fact, her mother entrusts me with a sleek, yellow pantsuit,

the likes of which would be worn by twenty-something clubgirls, to deliver

to her daughter, whom I am to interview in Cuba. Her daughter has been

the locus of the dollars she sends home, but Barbarita has also helped

plenty of people from her hometown once they reach Florida's shores.

So many of them have settled in Hollywood, in particular, that everyone

calls it "little Guayabal." She gives them a bed to sleep

on and food to eat and expects not a penny in return. Her most recent

guests have been her elder sister, Leopolda, who moved to Miami four

months ago. She and her husband, Osvaldo, and their daughter, Juliett,

share the spare bedroom in the Hialeah condo.

Leopolda, was named after

her grandmother, but she hates her name, preferring the nickname, "Poli."

She calls Barbarita the pretty one in the family, even though both women

are attractive with round faces and dark, piercing eyes. Both have bleached

their dark hair blonde, a custom among Latin women. Leopolda and her

family are here illegally. But nobody in this house, or in any other

house in Cuban Miami, is particularly worried about deportation. "Wet-foot,

dry foot" may have made it harder to get here, but the Cuban Adjustment

Act makes staying in the United States a cakewalk. The Cuban government

calls the Act "La Ley de Asasinas," the Law of the Assassins,

because it says it encourages Cubans to immigrate, even if it means

risking their lives to do so. As a piece of legislation crafted at the

height of the Cold War in 1966, the Act was a way for the U.S. to strengthen

the exile community in the hopes that one day, it would overthrow Castro

and vindicate the failed Bay of Pigs invasion. For Cubans, the Act was,

and still is, the strongest incentive to get to Miami, any which way

they can. It allows them to apply for their green cards exactly one

year after their arrival.

And that is exactly what

Leopolda, 46, intends to do in January. In the meantime, she works under

the table at a school cafeteria, while her husband, Osvaldo, works ten

hours a day washing cars. Her daughter, Juliett, goes to a neighborhood

school where nearly everyone is Cuban.

I watch Leopolda slice pork

for the family dinner one night, as a pressure cooker hisses in the

background. Our conversation veers between immigration and hunger. It

seems impossible to talk to Cubans about why they left and not broach

the subject of food. I ask her how much the pork would cost in Cuba.

"I wouldn't know,"

she says. "Because I could never afford to buy it. The few times

I ate pork was when our family would raise a pig. We would kill it,

and then eat it."

The pork in Cuba is exquisite,

she says. The problem is, you can't buy it unless you have dollars.

"That's why you have immigration," she says. "That's

why you have family separation. That's why you have tears," she

says, as if reciting a poem.

| Leopolda

sticks up her middle finger, and says: "In Cuba, this is what

voluntarism means."

|

Leopolda's own family is

separated between countries and continents. She has two grown sons from

a previous marriag, 26-year-old Alain who lives in Havana, and Alexei,

21, who moved to Spain in 1999. Alain has been unemployed for months,

and most recently got a job teaching computer skills to children. Leopolda

never blamed him for not working. She says it's impossible to work honestly

in Cuba. She dutifully sends her son $50 a month because she firmly

believes that in Cuba, "if you don't have family members in the

U.S, you're screwed."

Leopolda has a bluntness

not found in Barbarita, who often mentions how thankful she is that

she and her husband have been able to work and prosper in the United

States. It is too early for Leopolda to feel such gratitude. She is

still smarting with bitterness from the life she left behind. She left

Cuba because, she says simply, she didn't feel free. Unlike her sister,

who didn't pursue a career in Cuba, Leopolda worked as a nurse for 28

years at a hospital in Havana, eventually becoming the head of nursing.

Her seniority brought unwanted political obligations. As "una

jefa," she had to be a role model for her co-workers, showing

up to meetings and rallies at the Plaza de la Revolucíon in Havana.

"I was one of the first to go up there and say, viva Fidel, because

I had to do it," she recalls, sitting on the back porch, taking

a drag on her cigarette. "As the boss, I had to pretend. When there

is a meeting, when the plaza is filled, it's not that people go voluntarily."

She sticks up her middle finger, and says: "In Cuba, this is what

voluntarism means."

Applying for her exit permit

was an ordeal. As a health care worker, she had to get permission from

the health care minister himself. She applied to leave in March, 1999,

and for eight months she would go to the office every week to inquire

about her petition. "Every Wednesday, I would get up really early

to bug him about it. For me, it was like we were slaves because I couldn't

even talk to the health minister." Finally, one December morning

she got a call telling her she could leave.

She and her family moved

to Madrid and tried to forge a life there, which was difficult since

Spanish employers tended to hire "chicos y chicas," young

people, Leopolda says with sarcasm. So, she and her family packed their

bags and headed to Miami, where they wait now to start a life on their

own. Like her sister, she is thinking about the child she left behind,

even though her son is not a child, but a grown man. There's a knot

in my throat when I'm eating meat," she says of Alain. "You

don't really eat it with pleasure."

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

The joke in Cuba is to tell

someone that you have fe, meaning not hope, but "family

in the exterior." Anymore, though, having fe has turned

out to be a mixed blessing. For those who remain on the island, life

becomes more complicated after family members leave. Remittances allow

Cubans to survive, but at a social cost. The envy bred in those who

don't receive money from family abroad towards those who do can tear

a family apart.

So, too, has Barbarita's

family cleaved since her departure, and the fault line goes right through

Avenida 79 in Guayabal. On one side is Rosario Perez, Barbarita's elder

sister who lives in relative poverty compared to Miriam Azcuy, Orlando's

sister, who has become in loco parentis for Hany.

As I drive to Guayabal to

meet Rosario, I am accompanied by her nephew Alain, who lives in Havana.

He tells me "today, you will see what poverty is really like."

Until that afternoon, Avenida 79 had been defined by the Azcuy house,

an airy bungalow, smartly painted white with green trim, with a TV,

VCR, and handsome furniture, consumer goods purchased on the black market

with money Barbarita sends every month.

Rosario's house is constructed

out of drab, unpainted concrete. She shares one bedroom with her daughter,

a son, and a grandson. A few wall decorations made from cheap, gold

lame adorn the gray walls. Both the TV and fan are broken, unable to

provide relief from the boredom and heat of Guayabal.

Flies from the pig and chicken coop out back invade the house. Rosario,

a most gracious host, apologizes to everyone. Each time a fly falls

into a guest's orange juice, she whisks it away and replaces it with

a fresh one.

| As I

drive to Guayabal to meet Rosario, I am accompanied by her nephew

Alain, who lives in Havana. He tells me "today, you will see

what poverty is really like." |

Rosario feels badly about

Hany's predicament and says, "if only people were more humane,

they would let her go." I assume the people Rosario is referring

to are U.S. and Cuban officials. But no. It is Miriam who Rosario blames.

Rosario goes on to explain that Hany has already received an immigrant

visa from the U.S. government, but the Azcuys have failed to follow

up on the necessary paperwork. Hany also had a chance to go to the U.S.

by boat. But, Rosario confides, Miriam called the authorities, and the

boat trip was cancelled. Rosario's final barb is an accusation that

Miriam fails to inform her of phone calls from family members in Miami.

Down the street, Miriam

denies all of Rosario's claims, though it seems as if she has heard

them before. No, she says defensively, Hany has not received a visa

from the United States. And of course, if she received one, she would

go right away because her other documents—passport, and medical

records—are in order. Miriam stands nervously when she talks, making

it clear she wants us to leave. Her stress makes sense, since she has,

in fact, paid a price for being Hany's caretaker. In December, 1999,

she and her father were interrogated by state security in Havana about

the girl's status and had to spend a day in jail. The Cuban authorities

warned them if they allowed Hany to leave illegally, they would be thrown

in jail. State security even sends a representative to Guaybal every

once in awhile to check on them.

"If she got the visa

tomorrow, she would go tomorrow," says Ofelia, Hany's grandmother.

"It makes me laugh because they're lies," Miriam says about

Rosario's statements, her voice indignant. "She lies because she's

jealous of us. It's always something new with her. She should be embarrassed."

Once warm, the relationship between the two sisters-in-law soured when

Barbarita left in 1994. In the end, the fight was more about economic

inequity than Hany. "They've been upset with us, and they've always

had their own way," says Rosario about the Azcuys. "I don't

know if it's because they have better living standards than we do."

In Hialeah, Barbarita cries

when she finds out what Rosario said. She always thought of herself

as an exceptional sister to Rosario, she says. She had always helped

her sister in the past because as a single parent of five, Rosario needed

all the assistance she could get. "I was like a mother to them,"

recalls Barbarita. She says she doesn't send money to Rosario because

"from the moment I started working, I had to send money to Hany

and my mother. I left all of my belongings to Miriam because she was

taking care of Hany. "Rosario knew that. Everybody knew that."

Barbarita found out there was tension between the Rosario and Miriam

through a family friend. Yet she never brought up the issue to her sister

on her two visits to Guayabal. Ulimately, Barbarita corroborates what

Miriam tells me about Hany's visa, and says she is forever indebted

to her sister-in-law. "What Miriam is doing is priceless,"

she says. "I could die and I still wouldn't have thanked her enough

for taking care of Hany."

Immigration has been hardest

on those left behind without access to dollars. Rosario not only doesn't

have such access, but she is disconnected from the siblings who are

the closest to her. The four siblings who remain in Guayabal "have

their own families. They're not like the others, who are more concerned,"

she tells me on a walk around Guayabal, past the lush orange groves

that the government owns, but that everyone in the town steals from.

Rosario misses Leopolda the most, and keeps a passport-size photo of

her underneath a piece of glass on her bedside table. Leopolda has always

given her good advice, and has even lent her money on occasion. The

two of them have always been comraditas, best friends, since they are

only one year apart in age and share fond, childhood memories. "I

didn't want to say goodbye her when she left," Rosario tells me,

her eyes filling with tears.

Barbarita understands her

sister's problems, but can do little to solve them. Instead, she tries

to be the best mother she can be 90 miles away. She has left Hany with

Miriam because she trusts her sister-in-law to give her daughter as

normal a childhood as possible. Hany does all the things that a girl

growing in Guayabal would do: she goes to school, does her homework,

watches Brasilian soap operas on TV. On weekends, she has slumber parties

with her friends, or goes out with them to the town disco. She find

instant companionship in Miriam's own children, Sulesis and Davier.

She says she want to be model when she grows up. And as she picks through

her arroz con pollo one evening at dinner, she exudes the aloofness

and grace of someone who already belongs on a runway.

| Immigration

has been hardest on those left behind without access to dollars. |

She may, in fact, be having

a better than normal childhood than Guayabal's other children, if happiness

is measured by the size of one's doll collection or wardrobe. After

dinner, Miriam opens the armoire Hany shares with her cousin to reveal

a row of colorful dresses, fashionable pants with narrow waists and

flared legs, and body-hugging, Lycra tops. Dolls, ranging from miniature

blonde babies in nothing but diapers to a Barbie in full bridal wear,

take up an entire wall. There are four shelves stacked with shoes, a

Hello Kitty doll, a silvery purse, and teddy bears.

Certainly, it is not material

things Hany lacks. She feels free to ask her mother in their weekly

phone conversations for more clothes or shoes. Missing from her life

are mother-and-daughter talks best held in person. "I miss her

more now," she says. "If I want to confide in her, if I want

to ask her advice, I can't. Supposing I had a boyfriend. I could ask

her if she thinks he likes me."

The time right after her

mother's departure was difficult, too. She had to face the stigma of

classmates, who teased her because her parents left. One day, a girl

pushed Hany too far. "I scratched her face and grabbed her hair,"

Hany recalls. "I started dragging her by the hair. The little girl

was making fun of me because my parents had left. At the end of the

day, I couldn't take it anymore." Now, she lives with the memories

of her mother's brief visits. They went to restaurants, to the beach,

and bought school supplies for Hany. They did all the things that Barbarita,

on a tourist visa, could do. "At the aiport, there is a rope to

separate people who come and those who are waiting," Hany says,

recalling her mother's arrival at Jose Marti International Airport.

"I jumped the rope."

Postscript: Hany arrived

at her parents' home in Hilaeah, Florida on September 9, 2001. She is

attending sixth grade.

Back

to stories page