Cuba 2001

By Juliana

Barbassa

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

Heat waves rising from the

cracked pavement make the red flower print on a plastic bag shimmer.

A bored teenager, the third in line for a public phone, shifts impatiently,

her lemon-yellow Lycra top glaring bright in the sun. Second in line,

a man in a baseball cap checks her out, but settles his glance on the

tourist fumbling in her huge American backpack for change, a credit

card, or whatever these Cuban phones take.

"Where are you from?

Spain?" he asks, without waiting for an answer.

"Where are you staying?

When he finds out where, and that I'm paying $15 a night, he laughs

and rolls his eyes.

"I can offer you a

room for much less… Close by, a block and half, maybe two. Come

see."

Welcome to Cuba. The public

phone takes only dollars. So does the portly hot dog vendor taking advantage

of the phone line to sell ice-cold TuKolas — Cuban Coke —

and Havana Club Rum. So do the neighborhood kids, who give a lost tourist

directions for a dollar fee, and the cab driver, who won't take Cuban

pesos— even as a tip. They want dollars. So, in fact, does the

Cuban Government.

This may still be Castro's

Cuba, but the evils the Revolution came to vanquish— the dollar,

tourism, private enterprise and inequality--are pushing through the

widening cracks brought by the fall of the Soviet bloc.

Described by Castro as a

necessary evil, these small allowances to capitalism are taking root

and seeding change at every level of Cuban society.

| "It

was like giving an asphyxiating patient a breath of oxygen,"

says Marta, who rents rooms in her house. "First, he recovers.

Then he wants more." |

The advent of the dollar

and private enterprise means that the worker's paradise now has winners

and losers. Staying close to the party line and putting in a few hours

in a state-owned company for a peso salary no longer guarantee a good

living. This is a new game, and the one with the most dollars wins,

whether the money comes from hard work or from relatives abroad. Surprised,

Cubans are seeing the other face of government. In addition to public

service, which in Cuba includes health and education, the government

also taxes the entrepreneur and competes against businesses for tourist

dollars. Still, even with tight regulations, a little taste of economic

freedom goes a long way.

"It was like giving

an asphyxiating patient a breath of oxygen," says Marta, who rents

rooms in her house. "First, he recovers. Then he wants more."

To get more, Cubans everywhere,

in legal businesses and in underground markets tweak the rules and cheat

the state. Highly educated Cubans have dumped low paying professional

jobs to work in tourism for dollar tips. In the race for dollars that

followed economic reforms in the 1990s, Cubans use what they have: they

rent their houses, sell the country's communist appeal—Che beret'

and tee shirts--and invent a thousand ways to stretch what little income

they have.

During the special period,

as Cubans call the economic mess they have been sorting through since

the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, the easy credit

and cheap oil coming from the Soviets dried up. Cuban sugar, which had

been sold at artificially high prices, found no buyers, and the island's

fragile economy, fed on subsidies and barely standing on its old sugar

and tobacco legs, collapsed.

"With the demise of

the Soviet Union, we had to change, says Antonio Ravelo Narino, a Cuban

economist. "It was like a wedding; if one person dies, you can't

expect the other to go on living with the dead. We were trying to live

with the dead."

The government opened the

island to tourists and their dollars in the early 1990s, but that was

not enough. To control spiraling inflation, the threat of unemployment,

and a grinding depression, Castro gave in to what was already happening

in black markets and inside homes all over the island: he legalized

the possession of dollars. He also allowed small private enterprises

to flourish under tight regulations and permitted foreigners to invest

in mixed ventures.

"If we hadn't been

allowed to fend for ourselves, put up our businesses, things would have

exploded," Alejandro, the hot dog vendor by the payphone explains

as he polishes the shiny aluminum countertop.

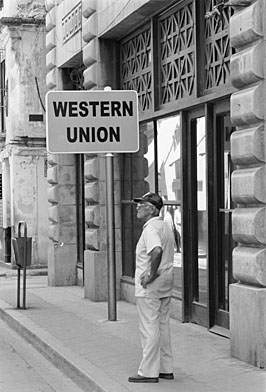

If Cubans had to scramble

for hard currency to survive, so did the government. When tourist dollars

were not enough to pay expenses and service Cuba's $22 billion foreign

debt, the government looked for ways to cash in on the remittances that

relatives abroad sent to Cubans on the island. The answer was government-owned

dollar stores. These quickly appeared on every corner, selling everything

from Italian biscotti to television sets. The majority of Cubans, however,

still lived on pesos, and with an average wage of 240 pesos – about

$12 dollars—no one earned enough. An average family needs at least

$50 a month to survive, so by the mid-1990s Cubans everywhere went into

the streets to make up the difference between their peso salary and

the dollar reality.

"This is the land of

magical realism," Fernando explains on the way to showing me the

room he has for rent. "Incredible things happen every day so that

people can go on. People invent."

Inventing a living is how

engineers like Fernando end up on a Havana sidewalk convincing a tourist

to follow him home. His is the story they all tell: his peso salary

in a management position with a state-owned company was never enough,

and since the legalization of dollars in 1993, he has been earning his

dollars any way he can--selling instant photographs that he takes of

couples in restaurants, renting pirated videos, and sometimes renting

a room in the home he shares with his sister. Inventing.

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

He has no license for renting

rooms, but like many other Cubans, Fernando has mastered the tight-rope

walk between punishable illegalities and everyday infringements that

most officials ignore. Renting videos was not one of the categories

of self-employment that the government legalized in 1993, but from the

second floor in one of Havana's old mansions, with soaring twenty-foot

ceilings, peeling paint and faulty plumbing, Fernando makes his own

rules. One tape goes for 25 cents, a bargain next to the official government

rentals--$5 a membership and $1 per rental. What's really priceless

is the selection: while state-owned video rentals limit the movies available

to those that have been officially sanctioned, Fernando's solid wood

china cabinet offers a range of new releases that rivals Blockbuster's

shelves: Terminator, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, and

300 others. Cubans, he explains, as he flips from channel to channel

through a pirated satellite hook-up, prefer action and violence. He

stops at the Playboy channel. "I don't record this stuff. A government

official might look the other way if his kids are watching rented movies,

but if they start watching pornography, then he might want to find out

where it is coming from," he says, shrugging off the question about

what would happen if he were caught.

"When ordinary things

become crimes, then you make an ordinary man a criminal," he says.

The television set flickers. Urban Legends, a popular series,

comes on. He starts recording.

Not all private businesses

on the island are outside the law. Currently there are 150,000 legal,

licensed businesses in Cuba, ranging from shoe-shiners and plumbers

to small restaurants and private homes that rent rooms to tourists.

A few chosen occupations—initially 110, now 157--opened up for

private enterprise in fits and starts. The number varies according to

governmental whim.

"The government tries

to limit this sector as much as possible" says Roberto Orro, a

Cuban economist now living in Puerto Rico. "It had to accept it

because there was no other option, but it was certainly against its

will. There are people who are not politically faithful to the government,

and now those people have the possibility of obtaining a certain economic

independence."

Paladares, for example,

the tiny restaurants named after a canteen in a Brazilian soap opera,

were ordered shut in December 1993, with Castro accusing the owners

of the still tax-free establishments of illicit enrichment. The need

to create employment and jump-start the economy forced the restaurants

open again weeks later. They operate under tight rules and close inspections

by several government agencies that have the right – if not the

manpower—to check everything from hygiene to tax compliance.

These regulations squeeze

many legal businesses underground. Once they disappear from government

lists, the businesses that give street life in Cuba its flair—1950s

taxi cabs, food vendors, cigar hawkers— flourish without taxes

or regulations, making enough money to pay the occasional fines and

still make a comfortable living.

Meanwhile, legal paladares

can only serve food bought at government-owned dollar stores at retail

prices. The rules say receipts must be kept handy for frequent monthly

inspections that come any time between 5 am and 10 pm. The establishments

are forbidden from having live entertainment, and must stay away from

main streets and popular tourist hubs. But it is difficult to know to

what extent these rules are respected, since even legal businesses seem

to follow some of the rules and ignore others.

|

Regulations

squeeze many legal businesses underground. Once

they disappear from government lists, the businesses that give

street life in Cuba its flair— 1950s taxi cabs, food vendors,

cigar hawkers— flourish without taxes or regulations, making

enough money to pay the occasional fines and still make a comfortable

living.

|

Take Fernando's favorite

paladar in Santa Fe, 40 minutes west of old Vedado, past the upscale

oceanside neighborhood of Miramar, and far from where most tourists

stray. We get to the seating area in the backyard by walking under the

front hedge, along the house, and through the patio where dozens of

caged parakeets hang amid ferns. When we emerge from the ferns, we run

into the restaurant owner, who stands elbow deep in blood, dissecting

fresh chicken. She prefers not to give her name.

"Our advertisement

are our clients," she says, explaining why no visible sign hangs

at the front. Her sister, squatting on the floor, inspecting buckets

of chicken parts, is more direct: "Unnoticed, we do much better

than by calling attention to ourselves."

A quick glance around shows

why the two sisters want to keep their secret: the first rule for paladares,

no more than 12 customers at a time, is disregarded. This place has

12 tables. A restaurant this busy also needs many employees, which according

to rules, should all be family members.

Are they?

"Well," says the

owner, laughing with her knife in hand. "It is as if we were all

a big family. Everyone puts this address in their identity booklets,

so that when inspectors come… you know."

I wonder if all that chicken

was bought from a government dollar store, as mandated by the law. These

are fresh, not frozen, and in residential areas like this, a quick stroll

is long enough to spot chicken scratching in the backyard, or the unmistakable

whiff of a home-grown pig.

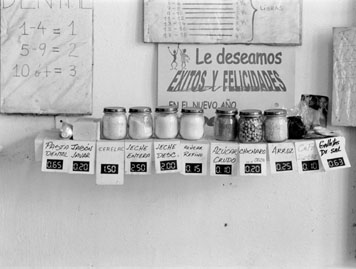

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

A scene from

a Cuban market. Currently there are 150,000 legal, licensed businesses

in Cuba, ranging from shoe-shiners and plumbers to small restaurants

and private homes that rent rooms to tourists.

|

A few feet away from the

owner, on white plastic tables facing the ocean, the guests enjoy fried

chicken and the breeze for just a handful of dollars. Far from tourist-heavy

Havana, this place caters to Cubans who have thrived in the changing

economy. The prices are lower than downtown-- $2.50 for rice, beans,

fried bananas, and fried chicken -- but still in dollars. The owners

have also done well, and the temptation to do even better is hard to

resist.

To attract business to state-owned

restaurants, the government does not allow paladares to serve seafood.

With the ocean a few feet away, and family member working as fishermen,

the two sisters are proud to point out that this is one rule they respect.

"There are those who take the risk, but we try to stay safe,"

the owner says. "So many of them have been shut down, but we are

still here."

As with Fernando's video

business, the secret of surviving lays in knowing which rules must be

respected, and in having a friendly relationship with your inspectors.

Watching the sisters, Fernando tells me about a friend who rents rooms

without a license, and pays his neighborhood inspector $50 a month to

get away with it. "One month, he didn't have enough. He told the

inspector, and immediately the man started naming the infractions he

was committing: renting a room, serving food to foreigners without the

proper sanitary precautions… My friend ran out and borrowed the

money really quick."

At an open-air market by

the Malecon, Havana's main seaside walk, William, a sculptor, echoes

these concerns. As he talks, he whittles ebony into the slender figures

of Cuban guajiros—peasants—and naked mulattas he sells to

tourists.

"They didn't tell you

to close down, but when they saw people were getting ahead in life,

they started to force you to close: taxes went up all the time, until

you were barely making a living, and the inspectors came at any time

of the day to see if all the people working have licenses."

William and his brothers

make a handsome living, finishing the month with more than $100 each

in a country where the average wage is $12. However, like other Cubans

who first experimented with profit a few years ago, he found taxes and

regulations to be an unpleasant yoke. In 1992, when he and his brothers

first started selling the sculptures they made as a hobby, they paid

nothing to the state, since what they did was illegal. In 1993, selling

arts and crafts was legalized—and soon the tax hikes began, from

$2 a month in 1993 to $159 a month, plus a $3 a day fee for using the

market. The monthly tax is fixed, independent of earnings, and another

year-end tax is based on revenue.

Other businesses also pay

taxes unheard of a few years ago: to rent a room to tourists in Vedado,

the homeowner pays a monthly tax of $250 per room; to run a private

cab that charges in dollars, the taxi driver pays $225 every month.

"Nowhere do people

pay taxes like this," William says, shaking his head in frustration.

It is hard to tell whether

William is really overtaxed, or just unfamiliar with the way capitalist

countries work. Even if they pay over half their income in taxes to

the government, Cuba's budding entrepreneurs are still making a killing

relative to others on the island. Williams complaints about taxes have

a familiar ring: he sounds just like small business owners everywhere.

He just doesn't know it.

"There is no small

business culture in Cuba," says Mayra Espina, a sociologist with

a prominent research center in Habana, the Centro de Investigaciones

Psicologicas y Sociologicas.. "They don't know how it works in

other countries, and they feel they are being strangled by taxes and

rules. When small businesses sprang up in Cuba illegally they had profit

margins of 500%; now, with 200% gains, they think they are suffering.

This doesn't mean the government isn't tightening the screws, but of

course they also have to contribute to the state, and follow rules like

everyone else."

In spite of their ingenuity

and flexible understanding of regulations, Cuba's entrepreneurs are

"a sector on the defensive," says Gillian Gunn Clissold, a

professor at Georgetown University. "The Cuban government has become

much more fierce about self-employment. It definitely is tightening

restrictions and imposing new ones." Santa Fe alone had 22 paladares

in the mid 1990s, when self-employment had just been authorized, and

Cuban families began to dream in dollars. Now there are only two. The

government is not issuing any more licenses for room rentals or paladares.

And this neighborhood is no exception.

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

"Self-employment was

never fully accepted by the government," says Espina. "They

saw it as a necessary evil, and the tension continues. When self-employment

goes up, there is always a reaction: taxes go up, inspections are more

rigorous, permits are no longer issued."

Legal self-employment in

Cuba has decreased at a rate of about 600 businesses a month for the

last three years. Of the 200,000 licensed businesses in 1996 only 151,000

remain, according José Luis Rodríguez, the Cuban minister

of the Economy. Some, like the owners of the paladar in Santa Fe, say

the ones forced out failed to follow rules. Others, like William, the

sculptor, feel the government is methodically squeezing the life out

of the sector through tax hikes and a draconian enforcement of existing

regulation.

Legal businesses may be

closing, as government officials say – but they might be simply

slipping off the official rolls, out of the government's grasp, and

into the island's booming underground economy, where no one pays taxes,

and the only rule is to stay in business. Flourishing illegal enterprise

helps Havana feel far from depressed. "There are a lot of people

doing this illegally," says Eugenio Espinosa Martinez, an economist

with FLACSO-Cuba who teaches in the University of Havana. "No one

knows how many, but you see them all over town."

In fact, any conversation

with a restaurant owner, or a stroll down old Havana's cobblestone streets

will show that even Cuba's legal businesses exist on both sides of the

law. Just about any curb-side stall offering sandwiches and pizza harbors

examples of the ingenuity that allows Cubans to survive. Instead of

buying all his wood from government supply stores, William, the sculptor,

whittles some of his figurines from the banisters and roof beams taken

from old Havana's crumbling mansions. The taxi driver who takes a tourist

home at night is likely to ask him to agree on a price beforehand, to

avoid turning on the meter: "You pay less to me, I make a little

extra money." Gisela, who rents rooms in her home, doesn't declare

all the rooms she has for rent.

Joaquina, a sociology professor

at the University of Habana who also rents rooms to make ends meet,

explains, "This isn't the black market; there is nothing hidden.

It is the market. Period." She started hosting foreigners during

the special period, "right around the time when even toilet paper

was scarce. I decided we'd had enough."

Her husband, Bienvenido,

is a sailor, and returned home from his trips with food and clothing

that the family could later sell to neighbors. Paying under the table

with black market money, they moved their four-person family to a five-bedroom

apartment with two bathrooms. More sailing brought more goods for sale,

and they bought beds. Soon they had a profitable bed-and-breakfast that

caters to the visiting professors and scholars Joaquina meets through

the university.

| "This

isn't the black market; there is nothing hidden. It is the market.

Period." |

In 1993, as soon as it was

possible, she legalized her business, and now pays the necessary taxes.

Her business is perfectly legal, but talking over breakfast, she explains

the web of small illegalities and daily infractions that she and others

participates in. Take the bread, she says, pointing to one of tasteless,

crumbling rolls Cubans buy at a subsidized price. "The bakery workers

stretch the government rationed flour and oil, making bread that weighs

just a little less than it should," she says. "At the end

of the day, they make extra loaves, which they sell for a profit to

people like me."

While she talks, the doorbell rings. The neighborhood pharmacist is

delivering her daughter's migraine medicine.

Home delivery, in Cuba?

"This medicine only

comes once in a while," she explains. "He knows we need it,

and that we can pay in dollars, so he got prescription from a doctor

he knows. When the medicine comes in, he brings it over. That way we

don't have to check at the pharmacy every week, and he makes a little

extra."

Joaquina and Bienvenido

established their bed and breakfast, and now live on the winning side

of the dollar divide. They can afford home delivery, weekends on the

beach with the family, and occasional dinners in one of Habana's paladares

where they drink their beers next to tourists. Like small business owners

everywhere, they needed capital to start up. In a country where credit

or loans are nonexistent, and salaries never see the end of the month,

raising money is one of the most significant barriers to establishing

even a small business like.

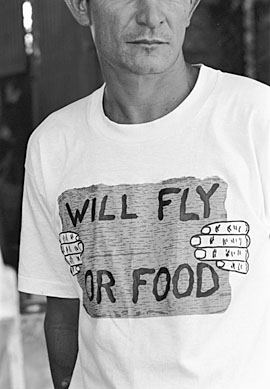

However, the dollars sent

by Cubans living in Miami, Spain or Costa Rica could change that. Already

the $800 million to $1.5 billion in yearly remittances supply would-be

capitalists like Fernando, who rents videos without authorization, with

seed money. He relied on money sent by his mother and brother who live

in Miami to buy the VCRs he needed to set up his video rental business.

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

Whether the money helped

start a business or put food on the table, remittances have been a lifeline

for the economy of the country, and for the families receiving them.

When the government legalized remittances in dollars in 1993, the country

breathed a collective sigh of relief. The Cuban government used the

tourist dollars and whatever it could capture of the remittances to

service the country's debt, to buy essentials such as oil abroad, and

to keep the bare essentials of its social system in place: subsidies

on basic food items, and Cuba's renowned public health and education

system.

"The net balance of

these measures was positive for the government," says Orro, a Cuban

economist living in Puerto Rico. "They managed to preserve the

regime, and people felt relieved."

Cubans had just gone through

the deepest depression in their history. Even the most basic necessities

had been missing, and so they welcomed remittances, foreign investment,

tourism, and all the measures taken to restore the country to some semblance

of stability.

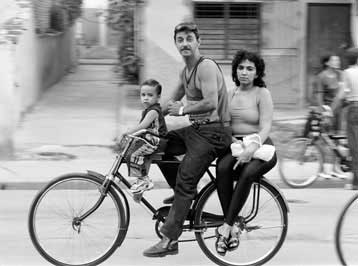

"During the special

period, we went through a phase called option zero, meaning zero gas,"

says Fernando. "Horses and mules were used even in cities."

Even today, bicycles and bicycle taxis are common means of transportation.

Cubans came close to starvation, Joaquina says. She remembers an epidemic

of scurvy in Habana, when fresh fruit could not reach the city. The

advent of the dollar changed all that. But even while they brought prosperity

to Cuba, dollars also brought inequality.

Salaries in state-owned

companies, which employ the vast majority of Cubans, are still low,

but recently teachers, police, lawyers, doctors and nurses were given

a raise. Some workers now get dollar bonuses that go from $5 to $20

as incentives to keep their poorly-paid state jobs, and to take the

edge off their frustration. Others, like Joaquina, get a monthly supply

of essential items only available in dollar stores, such as soap, deodorant

and toothpaste.

However, the gap between

the life these professionals lead with their peso salaries, raise and

bonuses included, and the lives of friends or neighbors who get $100

a month in legally allowed remittances is too deep to be affected by

a few more pesos or a month's supply of shampoo. Now, large income gaps

exist between neighbors and family members, and the relationship between

work and wage is distorted by the effortless affluence brought to some

families by the dollars from abroad.

"This is the negative

side of remittances," says Gunn, a professor at Georgetown University.

"In Cuba, you can live very well doing absolutely nothing, if you

are lucky enough to have relatives abroad. And you can work your butt

off, you can be the most industrious, hard-working, entrepreneurial

person onthe island,

but if you don't have access to dollars, your children are probably

running out of food at the end of the month. It has encouraged a mentality

that reward is not related to work."

The divide between those

with dollars and those without widens as Cubans who get money from abroad

put it to work, setting up their own businesses, and generating even

more dollars.

| "We

have to educate people all over again, to teach them to live in

a capitalist world, even if we are in a socialist country. Before,

after 10, 15 years working in the university, you got a car. You

had the right to a car. Now, no one gives you anything, though some

are still waiting." |

"This money betters

the quality of life of those who receive it, but they create a difference

among neighbors that did not exist before," says Marta, who rents

rooms in her apartment, and also receives money from her son in Miami.

A picture of him posing beside his car is on the living room coffee

table, facing away from the enormous home entertainment system that

takes up a corner of the room. "A simple salary in pesos does not

allow people to live with these same comforts," she says. "But

I see it as a necessary evil."

Not everyone likes Cuba's

new source of income, or the dollarized economy. Those who had bet on

staying close to the party and moving up the ladder, accessing scarce

privileges along the way, felt cheated as the relatives of immigrants,

who were at best ideologically suspicious, and the island's new petit

bourgeois became the new moneyed elite. "Many saw this as a betrayal,"

says Fernando. "They saw their possibilities diminishing along

with their salary. They

wanted to be recognized for their dedication to the common project,

and many really wanted an egalitarian society."

The shift away

from old Marxist rhetoric has been difficult, Joaquina explains. The

ones who learn fast take advantage of the new system. The ones who don't,

sink. "We have to educate people all over again, to teach them

to live in a capitalist world, even if we are in a socialist country,"

she says. "Before, after 10, 15 years working in the university,

you got a car. You had the right to a car. Now, no one gives you anything,

though some are still waiting."

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

While Cubans do their bit

of magic to turn pesos to dollars, the Government is doing the same,

trying to work its way out of an accumulated $22 billion debt while

propping up the educational and health system Cubans constantly tout

as the best in Latin America.

Cuba's strong economic performance

in the 1970s increased its access to credit from commercial banks and

international lending agencies, and the country borrowed heavily. Throughout

the 1980s, the Soviet Union subsidized Castro's island to the tune of

$4 billion a year. They also allowed Cuba to resell its surplus oil

for hard currency. As early as 1985, however, with sugar and oil prices

dropping, Cuba's situation started to deteriorate. The total debt reached

33% of Cuba's GNP, and by 1986 Castro declared a moratorium on commercial

debt and on debt owed to non-socialist countries.

As the Soviet Union disintegrated,

Cuba was left with this debt, exports that dropped 80% between 1989

and 1994, and a GDP that fell by half. Even as Cuba sank, the United

States continued to tightened the embargo.

Castro responded by opening

the island to hard currency, and he proved as ingenious as any Cuban

in devising ways to capture this bounty for the state. Now, dollars

will buy just about anything on the island, but behind every hotel counter,

every state taxi, and every dollar store is a government employee who

is paid in pesos. The greenbacks go to the government; the employee

keeps the tips.

This is also true for Cubans

who work for foreign companies doing business in Cuba. And there are

an increasing number. "The Cuban workforce is excellent,"

says Demarco Epifanio, the head of Brazil's Cuban subsidiary of its

oil company Petrobras. "But there are no links between Petrobras

and the Cuban employee; we contract them through the state. If I need

someone, I call CUPET— Cuba Petroleum. I pay them, for example,

$2000 a month for an accountant. They pay the accountant maybe some

400 pesos."

Four hundred pesos means

$18 – and the government pockets the difference. The same is true

in all foreign enterprise. Employees only keep their dollar tips.

| Chavitos

are an unusual economic tool, and one of the more curious aspects

of Castro's efforts to reap dollars for its own uses. |

But to make sure it gathers

even those modest sums and remittances, the government has established

Tiendas de Recaudacion de Divisas, literally, Stores for the

Recapture of Hard Currency. That's where Cubans must go for just about

anything they need.

And even by American standards,

the prices are high: $300 for a 13" television, $30 for a table-top

fan, $5.70 for cookies and juice. The inflated prices at dollar stores

effectively act as a hidden tax on the dollars Cubans earn in remittances.

Any attempt to tax this income would simply drive them underground,

so government stores absorb these dollars instead.

"These dollar stores?,"

asks Ravelo, a Cuban economist. "They're there for those who get

remittances. The government gathers up these dollars, and with them

buys what it needs."

Of course, there are Cubans

who do not have dollars. For their convenience, the government has posted

CADECAS— Casas de Cambio, or exchange booths—all over

the island. There, tourists can sell their dollars, but when Cubans

try to buy these dollars with pesos, what they get are Cuba's version

of Monopoly money— pesos convertibles, convertible pesos, or chavitos,

as they are known. On the island, they are worth the same as dollars,

and can be spent at any government dollar store. Leave the island, however,

and the game's over; chavitos have no value.

Chavitos are an unusual

economic tool, and one of the more curious aspects of Castro's efforts

to reap dollars for its own uses. With these convertible pesos in circulation,

"the government does not have to sell dollars," says Espina,

a Cuban sociologist. "They buy dollars, which they can use, and

they sell chavitos, which people can still use as if they were dollars."

Chavitos came about when

the government felt the need to reward state workers with some access

to the dollar stores, but did not want to let go of the dollars it had.

"Different sectors started emitting vouchers that were worth so

many dollars," explains Espinosa. "Soon, there were so many

vouchers in circulation that no one knew which ones were valid."

It is hard for the economy

to function effectively with three different currencies in circulation,

and economists agree that this measure must be limited to the period

of economic recovery.

| "Cuba

is preparing itself aggressively for the day the American embargo

falls," says Epifanio. |

How long that will take,

however, is anyone's guess. There are positive signs: since 1995, Cuba

started informal talks with the Paris Club of Creditor Nations, which

holds most of its foreign debt. The economy has been growing modestly

at 4.4% a year since 1995 with a projected growth of 5% in 2001. Foreign

investment, another main source of hard currency, continues to grow

substantially, particularly in telecommunications, mining and tourism.

"We need to learn to

compete within the harsh reality of a capitalist world, even as a socialist

country," says Silvia Domenech, a professor of economy at the Escuela

Superior del PCC, the Cuban Communist Party's school of higher education.

Since the legalization of

dollars, Cuba's economy has stabilized, inflation has slowed, and the

Cuban peso now hovers at around 22 to one dollar. The island still needs

hard currency, and Castro needs more than just a stable economy. "Cuba

is preparing itself aggressively for the day the American embargo falls,"

says Epifanio. "If it ended today, they'd be in trouble, because

the United States would take over with people and capital. They are

trying to develop their own infrastructure so they'll be able to stand

on their own."

To build the independent

Cuba that Castro and many Cubans believe in, the country is still working

hard to bring in dollars – from foreign investors, from family

abroad, or from tourists willing to exchange hard cash for the lingering

appeal of communism. Even Che Guevara's romantic image is for sale at

tourist markets, looking forever into a future that never came as Cubans

scramble in the present to balance along the dollar-peso divide. Never

mind that the $10 Che t-shirt, or a cheap reproduction of his red-starred

beret would cost the average Cuban a month's wages; this is the land

of paradoxes, and the impossible is shrugged off daily as people "invent"

ways of living in dollars while earning in pesos.

While the island braces

itself for whatever may come—real economic independence, or market-driven

globalization—Cuban citizens are doing the same. Fernando dreams

of getting an American MBA, and writes asking about the GMAT and university

applications. In Castro's Cuba, he is reading Adam Smith and John M.

Keynes, soaking up his lessons in capitalism straight from the source.

Inventing himself a future, wherever that may be.

Back

to stories page