Cyber Libre: Cubans Log

On Behind Castro’s Back

By John

Coté

Researchers: Cyrus Farivar and Osvaldo Gomez

|

|

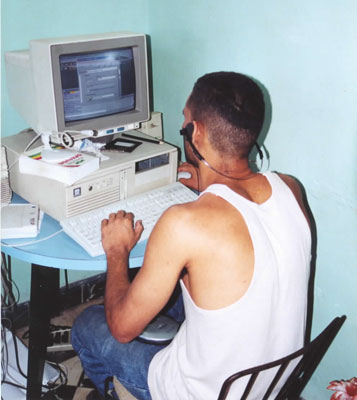

photo

by John Coté

A hacker works

in his Havana apartment.

|

The rooftop apartment in

Central Havana has black iron bars on the front window and door. Jagger,

a German shepherd, growls and charges the doorway, his lean head pressed

against the iron as he snaps at the visitors. Antonio Cuesta, a gangly

26-year-old Cuban with a crew cut, takes Jagger by the collar and chains

him to a yellow hallway door grooved with claw marks.

"Guard dog," he

says and flashes a smile. "When my mom’s here alone, he won’t

let anyone in."

Not quite comfortably out

of Jagger’s reach in the front room sits Cuesta’s passion:

a patchwork computer, the parts borrowed from friends or bought on Cuba’s

black market.

Before he sits down, Cuesta

looks at the visitors.

"If I get caught telling

you this, it’s 30 years," he says. "They’ll send

me to a place no one would ever want to go."

With a few mouse clicks

he brings up a list of pirated codes to access the Internet. He selects

one, and the modem dials.

No dice.

The code’s legitimate

owner might be logged on, or maybe the system is experiencing a glitch.

"Sometimes different

phone lines in different areas go down," says Cuesta. He shrugs

and clicks another icon. "So I have 11 accounts."

Hackers must be resourceful

to survive in a Communist world, where fraying infrastructure, snarled

bureaucracy and draconian security services are the norm. But cyber

criminals like Cuesta are not simply survivors; they’re an indication

that Fidel Castro is unable to control the inherently democratic world

of the Internet.

|

"If

I get caught telling you this, it’s 30 years," he says.

"They’ll

send me to a place no one would ever want to go."

|

Ever since the government

embraced la revolucion digital to make state-run companies more competitive,

it has tried to control popular access. For the most part it’s

been successful. Black market Internet accounts like Cuesta’s are

rare simply because most Cubans don’t have phones and can’t

afford a computer. In 1999 there was one personal computer for every

100 Cubans, far below the amount in other Latin American countries such

as Mexico, where, in the same year, one computer served every 23 citizens,

according to the World Bank. When a plan to increase and digitize Cuba’s

phone lines is completed in 2004, only 1 in 10 Cubans will have a phone,

according to Cuban government figures and census estimates. With an

average monthly salary of $20, many of those who do have phones are

not thinking about buying a computer, let alone a black market Internet

account.

The government also controls

the island’s four Internet service providers, whose traffic is

routed through a single state-controlled Internet gateway. Home Internet

accounts are restricted to foreigners, company executives and state

officials. Access codes are required to log on to the country’s

3,600 legal Internet accounts. That suffices for a population of 11

million. In addition, about 40,000 academics and government workers

have legal email accounts, half of them with access outside of Cuba,

said Luis Fernandez, a government spokesman.

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

That’s what the government

allows. But as Cuesta demonstrates, the Internet doesn’t stop there.

A small but lively black market has emerged. Sometimes legitimate account

holders want to supplement their state wages by selling their access

code. Other times, people like Cuesta steal codes while repairing computers

for company executives. Pirated codes go for $30 to $50 a month for

Internet access, $10 to $15 for email-only accounts. That’s too

steep for most Cubans, but affordable for some earning dollars off Havana’s

pulsing tourism. This new class of Internet users who circumvent government

controls is a testament to Cuban ingenuity, said a Western diplomat

in Havana who asked to remain anonymous. It also seems to indicate the

Cuban government can’t completely leash the teaming world of online

information.

Cuesta should know. On the

third try his modem hisses its familiar singsong, and this time a server

elsewhere on the island squawks back. He doesn’t look up from the

monitor, but a sharp smile flashes across his face. It’s the smile

of child telling his friends he just got away with cheating on a test.

"Look," he says,

pointing as his Netscape browser opens. "Where do you want to go?"

Soon Cuesta is on Hotmail

checking his email.

"This is the account

we should use – it’s not Cuban," he says. "The government

doesn’t look at it, and it’s faster."

Cuesta has reason to be

concerned about government surveillance. Black market Internet accounts,

largely copied or stolen from someone authorized to access a server

at a company or government institution, usually don’t warrant jail

time. But Cuesta’s case is different. "In general people who

have access are related to someone in power. They get fired, they take

away their Internet access, and they fine them," he said. "This

is not similar to my situation. I’ve done illegal work for them."

Cuesta clarified. "Them" is the government. He pauses and

looks down. When he raises his head, the smile is back. "The state

prepared me to steal secret data," he says.

Cuesta, who asked that his

name be changed, says he was trained as a teenager to be a government

hacker. Sitting in worn jeans and a knock-off Calvin Klein T-shirt,

he hardly looks like a covert state operative. His story could not be

verified beyond his stash of illegal access codes, but the respect he

commanded from other informaticos, or "computer geeks," was

unassailable. His computer knowledge was likewise extensive, and, given

the shortage of computers on the island until recent years, it seemed

unlikely he could reach that skill level without formal training.

|

"The

state trained me to circumvent passwords and access databases,"

he says.

"They

would buy software and then I’d be paid to break the dynamic

code so we could load one copy on all the machines."

|

With palpable caution, Cuesta

describes excelling at science at an early age. When he was 14 he was

selected to attend a specialized science boarding school. There he was

introduced to computers, and soon after he arrived, Cuesta says he started

working on computer viruses for fun. While at school he studied Trojan

horses – programs that appear to be useful but then launch a virus

or an unintended function – and had written a virus by the end

of his first year. "I demonstrated it to the professors,"

he says and laughs. "They were a little bit jealous."

Even at 14 Cuesta says he

had to look beyond his teachers for inspiration. He found it in his

21-year-old girlfriend, who was studying cybernetics, the theoretical

study of communication and control in machines and animals. "I

would study with her," he says and pauses for a moment. The smile

is back. "We would exchange ideas."

After graduating from the

science high school he sharpened his computer skills at the Eduardo

Garcia Delgado Electronics Institute in Havana. At 21 Cuesta says he

went to work for a state-run construction company that specialized in

large projects like airports and hotels. His job: hacker. "The

state trained me to circumvent passwords and access databases,"

he says. Most of this training came on the job at the construction company.

"They would buy software and then I’d be paid to break the

dynamic code so we could load one copy on all the machines."

Cuesta says his company,

which was in competition with other state-run companies, would get one

copy of the cheapest and most basic version of a program. It would be

designed to be loaded on only one computer. His job was to crack the

software security and install unlicensed programs on however many computers

the company needed. He says he would also hack into other companies’

computer systems – either the software designer or a company that

had a better version of the program – to steal information or computer

code to upgrade his company’s version of the software. Trade-specific

software for designing a large hotel, for example, could then incorporate

more variables and make more complex calculations.

An agent in the FBI’s

computer intrusion center and an executive for a U.K.-based computer

and Internet security firm both say the situations Cuesta describes

are plausible, but neither had any first-hand information about hacker

attacks by Cuban companies.

Cuesta says at his job he

targeted both foreign and Cuban companies – whatever it took to

make his company more effective. "The state owns every company

and business, but each must finance itself. They are in competition,"

said Cuesta. "But no one important can really go out of business.

It’s a false economy."

Disillusioned with the poor

treatment and meager salaries at state-run companies, Cuesta quit his

job at the construction firm in January and decided to try the world

of freelance programming. With two partners he does contract work designing

software and Web sites. The work is not sponsored by the state, and

therefore illegal. To minimize the danger for both the contractors and

the programmers, the business relationship is deliberately murky. Cuesta

says he and his two associates are currently designing software for

an Italian company. When asked, he says he doesn’t know the name

of the company, just the names of contact people he talks to weekly.

And the Italian contacts don’t know Cuesta’s partners. "It’s

not convenient for them to know who we are," Cuesta says. When

asked if he wanted to know more about his employers, he shakes his head.

"It’s better to know less."

The nature of the work promotes

secrecy. Cuesta says the Italian company would be expelled from Cuba

for contracting a group without government oversight. He also said because

the work is illegal, he and his colleagues write software using whatever

means necessary. He says they copy sections of code from patented software

and hack other useful information from databases. When speed and file

size are a factor, he turns to a friend at ETECSA, the Cuban phone company.

The friend sneaks Cuesta into ETECSA after hours to use its contemporary

machines and high-speed connection, a considerable improvement over

Cuesta’s 28.8 kbps modem and 133 megahertz Pentium I desktop. But

he’s coaxed that computer into performing beyond its capacity.

Most computer towers have multiple bays inside for hard drives, allowing

for an additional drive to easily be added. But Cuesta has jerry rigged

two 1-gigabyte hard drives to operate simultaneously in one bay –

taping a white plastic bag between them to keep their electrostatic

charges from shorting each other out. He also doubled the capacity of

one drive by using an application called Double Spacing. All this gave

him three times the original 1 gigabyte of hard disk space.

But these details are of

little consequence to his Italian employers, who, according to Cuesta,

want software they can sell as their own on the world market.

"They want cheap software,"

Cuesta says. "And we want dollars."

The quest for

dollars doesn’t stop at Cuesta’s front door. From there one

can look across stained rooftops sprouting TV antennas and makeshift

satellite dishes to the Capitolio, the domed Cuban capitol modeled after

its counterpart in Washington D.C. From the broad granite stairs radiating

heat to the air-conditioned Internet café tucked off the main

hall, the push for dollars is evident. Hawkers on the steps charge $1

for a bill with a picture of Che Guevara on it worth 14 cents. A box

of suspect Montecristo cigars goes for $40. But neither these Cubans,

nor someone like Cuesta, are allowed in Cybercafé Capitolio,

where another type of business goes on.

|

"It’s

called inventa," says James Philips, a foreign national

who has frequented the Internet café regularly during his

four years in Cuba.

"It’s

a creative way of stealing. … Say you’re online for

two hours. You pay for that two hours, but they ring it up as

one hour and pocket the rest."

|

The Internet café

– the first in Cuba when it opened in April 2000 – provides

Internet access on seven computers for $5 hour. Pesos are not accepted,

and the café’s commercial license only allows foreigners

and Cuban nationals married to foreigners to use the computers, says

Rolando Garcia, the café manager. Customers’ passport numbers

are written down before they can get online.

Garcia says the restrictions

were simply a business decision, not a move to control access to information.

He dismisses the notion that Internet access could facilitate social

change in Cuba. "The revolution isn’t afraid of this,"

says Garcia. "The revolution is already committed to educating

the population." He says he wants to apply to the Ministry of Science,

Technology and the Environment, which controls the café, for

a license allowing Cubans to get online, but he hasn’t started

the process yet.

Most Cubans simply can’t

afford to pay $5 for an hour of surfing. If they can, Garcia says they

would still be turned away. But one of the cafe clerks, who asked to

remain anonymous, says Cubans who can pay could get online.

"Today is a slow day,"

says Garcia, glancing around the narrow room where four café

tables are squeezed between floor-length windows and a counter. While

they wait for a computer, tourists drink bottled water and beer at the

tables or mill around a rack of Castro and Guevara postcards. "There

are more or less always 20 to 25 people waiting," Garcia says.

While that may be an exaggeration

– on several trips to the café before 10:00 a.m. only two

to three people were waiting – business is undoubtedly good. Garcia

wouldn’t give specifics on how much revenue the café was

bringing in, but he says he wanted to get permission from the ministry

to reinvest some or all of the operational income. "Right now we’d

like to finance ourselves," says Garcia. "We’re working

on changing to a much bigger and more comfortable location."

The ministry may be wary

though about the short-term loss of hard-currency. Besides the initial

investment in the computers and the cost of Internet service, the café

has little overhead. Garcia says his salary is about $12 a month. The

six other employees make less than Garcia. The café looks to

be a cash cow, and Garcia says similar operations have been opened in

the cities of Santiago and Santa Clara.

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

The government is also not

the only one getting dollars from Cybercafé Capitolio. The workers

are too. "It’s called inventa," says James Philips,

a foreign national who has frequented the Internet café regularly

during his four years in Cuba. "It’s a creative way of stealing.

… Say you’re online for two hours. You pay for that two hours,

but they ring it up as one hour and pocket the rest." According

to Philips, who asked that his real name not be used, the practice of

shorting the register is common anywhere dollars are paid. "It’s

the same thing at the grocery store," he says. "Everything

works on the dollar and informal client relationships. After I’d

been going to the Capitolio for a while, one day they just said I was

next. There was a list of names in front of me."

Philips said he was online

for about a half hour. His bill was $3. He gave the clerk a five-dollar

bill and told her to keep the change.

"The next time there

was a line and it was simply ‘We’ll fix it,’" says

Philips. "They’re not supposed to accept tips, but I know

they’re keeping that money." After that Philips says he no

longer had to wait in hour-long lines to check his email, and he always

tipped when he paid. Soon after he says an employee at the café

offered him a black market Internet account for $50 a month. When approached

months later by a foreign national posing as a student living in Cuba,

the same employee said he could arrange a black market account. A meeting

was scheduled with the employee’s "friend" who supplied

access codes.

Philips, however, got a

black market account for $50 through a different source. "I don’t

even know his name," Philips says. "I just call him Jorge’s

friend. He shows up every month for his money. He calls occasionally

to make sure everything is OK."

Depending on the type of

black market account, service can be spotty. According to multiple sources,

black market accounts are usually created in one of three ways: the

access code is stolen, the access code is sold by the legitimate owner,

or an illicit account is created by a network administrator who oversees

a server.

| "Generally

people who have Internet access are directors; they don’t know

anything about computers," says Cuesta. "We steal the

accounts and just sell the codes." |

"Let’s say you

work at CITMATEL [one of four government-run Internet service providers]

and you work for pesos," says Nelson Valdes, director of the Cuban

Academic Research Program at the University of New Mexico. "During

the day you create a program to set up a proxy server on the commercial

server. Now you have two servers effectively working on one. You’re

the only one who knows it’s there, and you can sell accounts for

dollars. … It happens all the time." Free software to set

up a proxy server is readily available through online chat channels

like Internet Relay Chat, or IRC. Valdes says that while doing research

in Cuba he paid $15 a month for an email-only account set up illicitly

on a proxy server.

Stolen access codes can

be the most problematic for Web surfers. If the code is for a single-user

account, the legitimate owner may try to log onto a server, only to

be denied because someone else has taken his or her place. Often the

account owner will request a new code, canceling the original one. The

cut-off black market user then tells his supplier, who gives him or

her a code from a different source. "Sometimes it works for weeks,

sometimes for a month or so," says Philips.

"I have a multiple-user

account," says Cuesta, the hacker. The account, which he says he

stole from a company executive, allows a set number of people –

an executive management group, for example – to dial in remotely

at the same time. Since there are multiple login slots available, there

is less chance an authorized user will be denied and realize the code

has been compromised. "Generally people who have Internet access

are directors; they don’t know anything about computers,"

says Cuesta. "We steal the accounts and just sell the codes. …

Also, I have a lot of friends who give me connections anyway."

Some individuals with legal

accounts sell their code to make cash on the side, they then set up

specific time periods for use.

"My friend has an account

that he can only use between 8 at night and 8 in the morning when the

owner isn’t using it," says Marelys Herrera, a 21-year-old

writer who shares a black market Internet account with her mother. Her

friend pays $30 a month for the limited service. Herrera and her mother

do a little better. "My mom works for a foreign firm," she

says. "The firm hooks her up and pays the $10 for the account,

but of course it’s illegal."

The unregulated nature of

the black market makes it impossible to tell how many Cubans are sneaking

online or buying used computer parts to circumvent costly and restrictive

government stores. Even more widespread is unofficial email use. There

are about 40,000 registered email accounts in Cuba, but many account

owners share their addresses with neighbors, friends and colleagues.

They print incoming messages for these other users and type in outgoing

emails.

Cuban students linger around

the stairs to the central library at Havana University, where foreign

students can open an account for $5 and send email on text-only computers

running a Linux operating system. Cuban students are rigorously questioned

and often denied an account, so they pass hand-written messages with

an email address scrawled on the top to any foreign exchange student

willing to send it.

"How many people have

email connectivity? We don’t know," says Valdes. "One

account can have eight people using it." Valdes says there are

"easily 20,000" free Yahoo! email accounts registered to Cubans.

Many of these people don’t have regular computer access, so they

set their accounts up to forward email to a friend who has regular access,

he says.

Though more rare than surreptitious

email use, everyone from painters to diplomats say they know about the

black market in computers and Internet accounts. "It’s rare,

yes," says Herrera, who asked that her name be changed. "But

in my world, pretty much everybody has black market access. We also

share computer parts and things like that. In my world we’re all

informaticos."

Informaticos say

they dodge the system for two main reasons: money and anonymity. If

one can get government approval, an Internet account is prohibitively

expensive unless a state agency subsidizes it. The National Center for

Automated Data Exchange, known by its Spanish acronym CENIAI, oversees

Cuba’s four Internet service providers. CENIAI charges $260 a month

– more than the average annual salary of $240 cited in United Nations

figures for 2000 – to Cubans and foreigners alike to register an

Internet account.

"You can go the official

way through CENIAI, but that way they know everything," says Herrera.

"They know exactly when you get on, exactly where you go, what

numbers you call. The service is better, but we don’t use it because

of that – and it’s expensive. So you just go through the black

market. You find someone who has it and ask them how they got it. It’s

really easy to get Internet access."

The black market

is also a primary source for computer hardware. "You pretty much

have to use the black market to build a computer; it’s a fortune

to buy one in the store," said Herrera. Pedro Mendoza, a 35-year-old

painter, turned to the black market to get a used desktop with a Pentium

III processor for $900. "There’s a black market for everything,

but you need money," says Mendoza. "You find it. It’s

that easy. That’s where you go if you want to get something done."

But not all

Cubans have the money to shop the black market, or have Cuesta’s

ability to get online themselves. These people have to go the official

route, which is cumbersome and restrictive. At the National Library

of Science and Technology, downstairs from the Cybercafé Capitolio,

average Cubans can get online information, but they can’t get online.

Instead, they submit requests to professional researchers who search

the Web on one of seven computers. The fee is 15 pesos per hour –

about 70 cents.

"We don’t

have sufficient technology to serve every Cuban," says Anierta

Pereira, a 37-year-old researcher at the library. "There are limitations."

One of the

limitations is that foreigners are given priority, says Pereira. "The

only thing is they have to pay in dollars," she says. Foreigners

are charged $5 an hour for research, or they can get online themselves

in the next room, where there are six computers with Internet connections

for the same $5-per-hour rate.

According to

Pereira, most of the information requests come from academics or students.

Pereira says no Web sites are blocked at the library, but superiors

can monitor researcher’s movements.

To demonstrate,

Pereira opens the Web site for the Cuban American National Foundation,

the largest U.S.-based Cuban exile group, which is known for its militant

anti-Castro stance. "You see?" she says. "We can access

anything, but it’s the time. We have to be productive. … The

cost to use the Internet is very high, and we don’t want to put

the institution in a position where they have to pay more money."

The Internet

is more expensive in Cuba than elsewhere. Pummeled by economic hardship

as the West leapt into the information age, Cuba is struggling to modernize

an antiquated telecommunications system that wasn’t built to handle

electronic data traffic. There are no fiber optic links off the island,

and all digital data is relayed through two costly satellite links.

In a bid to catch up, the government is overhauling its phone network

in a joint venture with Italy's Telecom Italia and Mexico’s Grupo

Domos, digitizing analog lines and laying new cables. When the project

is completed – slated for 2004 – there will be 1.1 million

phone lines. That is less than one phone per 10 Cubans. Now there are

about 623,000 phone lines, or one for every 18 Cubans. More than half

of these lines are analog and effectively useless for sending digital

information.

| "We

know the government monitors chat rooms," says Santiago Ferrer.

"If you say something out of the ordinary they kick you out of the

chat room. They have spies who are moderators." |

The government

frequently cites the lack of infrastructure and current Internet costs

as the main hindrance to Cubans getting online. To address this, communications

officials announced a plan to set up email and "Internet"

terminals in 2,000 post offices across the country, allowing even rural

Cubans to get online. In March three post offices were wired, and another

30 were brought online in April. "We had to find a way to use the

Internet for the public," said Juan Fernandez, head of Cuba’s

e-commerce commission. "Here really the only restriction for getting

on the Internet is technology. Cuba is not afraid of the challenge of

the Internet."

Fernandez’s

assurances seem hollow, however, considering the post offices that are

wired don’t offer Internet access. Rather, they provide access

to a national Intranet, a closed network that only contains sites endorsed

by the government. Cubans have to pay in dollars – $4.50 for three

hours – to surf the domestic Intranet or to send email internationally.

Web-hosted email accounts like Yahoo! Mail or Hotmail are not accessible.

Ostensibly Cubans are allowed to send domestic emails for 5 pesos per

hour, but at the main cyber post office inside the new Ministry of Information

and Communication the clerk said even domestic email had to be paid

for in dollars. Later, a second clerk at the same post office said domestic

emails could be paid for in pesos, but she didn’t know what the

rate was. "Almost no one uses pesos," she said.

"We have

to be realists," Sergio Perez, head of the Cuban computer firm

Teledatos, told the government-controlled newspaper Granma in

April. "Cuba, a poor country which is economically blocked by the

biggest imperialist powerhouse in the world, has food rations and a

shortage of medical supplies. How is it that we also wouldn’t have

Internet access limitations?"

While Cuban

officials frequently blame the U.S. trade embargo for the country’s

economic problems, the U.S. Treasury Department, which oversees U.S.

financial dealings with Cuba, authorized U.S. companies in 1997 to negotiate

with Cuban officials on opening a fiber optic link between Florida and

Cuba. The move came after the State Department issued a policy statement

earlier that year indicating it supported a fiber optic link to increase

the flow of information and cut high phone rates between the two countries.

The only condition was that no new technology could be given to Cuba.

"Our end

goal is that there would be a fiber optic cable so that we could encourage

a greater development of Internet between the United States and Cuba,"

says James Wolf, economic coordinator for Cuban affairs at the State

Department. "To our knowledge there has not actually been an agreement

between the Cuban phone company and any of the U.S. companies that have

been looking into this."

A fiber optic

ring being laid around the Caribbean should be completed by the end

of 2001, but in its current form it bypasses Cuba. Some observers have

speculated the network, know as Americas Region Caribbean Ring System,

or ARCOS-1, could be linked to Cuba if the political and business factors

fall into place. When completed, the ring will pass within 50 miles

of Havana, at which point an ARCOS-1 network map indicates a "branching

unit" will be laid down. The international consortium funding the

project includes 25 telecoms from 14 countries, including AT&T,

MCI and Genuity (formely GTE).

Wolf would

not comment on whether the consortium was negotiating with the Cuban

side, but noted, "at this point there has not been a single application

by any company to actually install such a cable." Valdes, director

of the Cuban Academic Research Program, framed the question facing the

Cuban government in economic terms: "Do we bring in optical lines,

or do we bring in pipes so we don’t have to truck in water to Havana?"

The Western

diplomat in Cuba, however, viewed it differently. According to him,

the Cuban government is making substantial revenue off high phone charges

between the U.S. and Cuba. Operating an efficient fiber optic network

with a U.S. business partner would cut into its revenue stream. For

U.S. government approval, the network would also have to allow for the

free flow of information, undercutting the Cuban government’s ability

to filter or monitor where its citizens venture in cyberspace.

It is unclear

how extensive government control over cyberspace is. In March it blocked

access to web phone sites like dialpad.com and online conferencing services

like Net Meeting. But both government-run computer centers and home

computers had access to sites from anti-Castro groups and U.S. media

outlets.

"It is

absolutely false that the government is controlling specific sites,"

Perez was quoted in Granma as saying. "It is the companies or institutions

connected to the Internet that decide where its workers and students

browse. In what country in the world is a doctor allowed to use a hospital

computer to visit porn sites or chat with a friend?"

In Cuba though,

all companies are owned by the state, and many computer users say they

are certain the government monitors Internet activity. "Everyone

knows it," says Santiago Ferrer, and a 25-year-old technician at

CUPET, the state petroleum company, and a friend of Cuesta’s. "It’s

in the technology. Servers have the capacity to look and check where

you were." Chat rooms are dangerous places because the government

watches them for subversive talk, says Ferrer. "We know the government

monitors chat rooms," he says. "If you say something out of

the ordinary they kick you out of the chat room. They have spies who

are moderators." According to Cuesta, all chat rooms in Cuba are

controlled. The government can even monitor individually set up a channels

that host invitation-only chat rooms.

But just the

threat of monitoring may be an effective deterrent. "You don’t

have to check someone’s urine everyday to see if they’re taking

drugs," said the Western diplomat. "I would be astounded if

they weren’t monitoring my every key stroke."

Even someone

like Armando Estévez, a well-placed state employee, isn’t

entrusted with Internet access. Relaxing in the afternoon sun on the

front steps of the Capitolio, he checks his IBM personal organizer and

his cell phone, conveniences someone like Cuesta only reads about. The

information services manager at CUPET, Estévez even has a laptop

to work from home, where he can dial into a closed company Intranet

but not the Internet.

| In the

Cuban cyber realm – whether it’s assembling computers

bought in pieces or selling Internet codes – it comes down

to ingenuity, connections and money. |

Still, he plays

down the idea that the government was worried online information could

stir political change. "Undoubtedly there is an influence, but

the political change is not very big," he says. "That information

is coming into the country all the time – it has been for 40 years.

We can’t blockade that kind of information. You hear it over the

radio or by word of mouth. People know what’s in the Miami Herald

and compare it with Granma."

Estévez

suggests Cubans view the U.S. newspaper and the Cuban state-run daily

with equal suspicion. "The problem is the lies are very big on

both sides," he says. "You can spot them immediately. That’s

what politics is."

With almost

2 million Cuban immigrants in the United States, nearly all of the estimated

11 million people in Cuba have a relative living somewhere across the

Florida Strait. Travel restrictions relaxed in 1999 under the Clinton

administration have allowed many Cuban émigrés to visit

the island, bringing news and goods from the United States. Thousands

of tourists visit annually, many of them from Western Europe. Miami-based

Radio Marti, funded by the U.S. government and operated by the Cuban

American National Foundation, broadcasts programs heard across Cuba.

According to Estévez, the Internet is "changing the minds

of the people," but in a personal way rather than a political one.

"People

use the Internet for communication, mainly personal communication,"

he says.

Ferrer, both

a colleague of Estévez’s and an informatico friend of Cuesta’s,

typifies a new generation of Cubans who get online to communicate. "It’s

very Cuban to cooperate through chatting," says Ferrer, who goes

by "macdaddy" in chat rooms. "Usually when we’re

chatting we get phone numbers. We meet at the beach and stuff. It’s

really weird and kinda funny. No one uses their real names when we meet.

They say, ‘Hey Mac Daddy,’ and you don’t know whether

to use their real name or not."

Despite the

lack of home Internet access, Ferrer says chatting is "very common

in Cuba now." He chats on the job. Monitoring the flow of petroleum

during a 24-hour shift has its down times, but Ferrer is friends with

the network administrator in his division. Even though he is not authorized

to have Internet access on his computer, Ferrer said the administrator

lets him get online whenever he wants.

"If you

chat at lunch my boss won’t do anything," he says. "It’s

not a problem. We shouldn’t chat it in front of him when we’re

supposed to be working, but we can surf the Web." Ferrer says surfing

is actually part of his job responsibilities. "My boss knows. Everybody

knows," he says. "My boss tells me to find stuff on the Internet."

As he talks,

Ferrer leans against a glass display case in the electronics store at

Havana’s Plaza Carlos III shopping center. He is among a group

of twenty-something males looking wistfully at a new shipment of modems,

motherboards and other computer gear, most without price tags. According

to the store manager, the parts arrived three days ago, and the store

headquarters hadn’t decided how much to charge. The few items that

had prices were two to three times more expensive than in the United

States. A Multi-Tech Systems 56K modem was $230. The same modem is listed

on buy.com for $115. Similar markups are found in the few other computer

stores sprinkled around Havana.

Ferrer is building

his computer piecemeal, cobbling together parts bought on the black

market or loaned to him by friends like Cuesta. He still needs a monitor,

a CD-ROM drive and a modem to complete it. "It’s very expensive,"

he says, casting a sidelong glance at modem. "Most of the parts

I have I got from friends."

Cost is not

the only factor when purchasing a computer. Prospective buyers must

have written permission from a company or government institution, like

the professional writers union, to buy a complete system. They then

have to purchase the computer with a check, usually drawn from a company

or government account, since few Cubans have personal bank accounts.

Computer parts can be bought without authorization, but in all cases

the transactions are in dollars.

| "If

you chat at lunch my boss won’t do anything," says Ferrer.

"It’s not a problem. We shouldn’t chat it in front

of him when we’re supposed to be working, but we can surf the

Web." |

According to

Ernesto Reyna, manager for the Plaza Carlos III store, anyone can come

in and buy all the parts to build a complete computer system at one

time. Although no hard drives, CR-ROM drives or tower cases were on

display, Reyna said the store had everything to put together a full

system. Once the pieces are bought, Reyna says staff will assemble the

machine if the customer requests. A Pentium III system with a CD-ROM,

modem and speakers would cost just over $2,000 – more than double

the price in the U.S.

In the Cuban

cyber realm – whether it’s assembling computers bought in

pieces or selling Internet codes – it comes down to ingenuity,

connections and money. Cuesta operates at one extreme, but the rules

are the same even at the shiny state-run computer clubs he describes

as "bullshit."

The government

started opening the clubs in the 1990s to help Cubans succeed in a technology-driven

world. Affiliated with the Union of Communist Youths, a government student

organization, the clubs teach classes in Windows, Excel and Word, as

well as more advanced skills like web design and multimedia presentations.

They focus on youths, but offer classes for adults as well. There are

currently 174 of these clubs throughout the country, said Damian Barcaz,

technical assistant director at the Central Palace of Computing, the

flagship club. He said the government plans to have between 200 and

300 throughout Cuba’s 15 provinces in the next two years.

"There’s

really nowhere you don’t need a computer," says Barcaz. "It’s

the way to the world." But many of these youth computer clubs,

like the one is the Havana neighborhood of Vedado, lack Internet access.

At the Central Palace of Computing in Old Havana, five of the 10 computers

available for students to do work outside of their classes have Internet

access. Barcaz says no sites are blocked or filtered out, bringing up

CNN’s Web site when asked. "Staff walk around and can look

where the students are going, but we don’t block anything,"

says Barcaz.

Upstairs from

the main hall, past a framed placard on which Castro wrote "Siento

envidia!" (How would you translate that?) when he christened the

center in 1991, a group of six- and seven-year-olds sit two to a computer

in a modern classroom. They practice their spelling as brightly colored

graphics of leopards and buses appeared on their screens. One boy uses

the mouse and keyboard to color in a graphic of Peter Pan and then write

a few words about the scene. Barcaz says the exercises teach young children

basics like how to use a mouse and turn on a computer while also developing

on language skills.

|

"Many

writers don’t have computers at home," says Joanna Ramirez,

20, one of the café administrators.

"Writers

can work on their books here and then send them to other countries

for interaction and discourse."

|

In the next

classroom the mood is more serious. Groups of three or four adults huddle

around each of the nine computers as they practice using Windows 2000

and Microsoft Excel. Many say they needed computer skills for their

job. "At my bank there’s one computer and I have to know how

to use it," says Leticia Betancourt, 23. "This is the only

way we can learn how. Society demands that you know how to use a computer

now, so we come here."

Marta Baros,

a 50-year-old accountant, is in a similar position. "I want to

be able to use this," she says, gesturing at an Excel spreadsheet

open on her screen. "If I can, my work will be much better."

With 1,040

students enrolled at the center, and thousands of applications received

before new courses start every four months, it appears many Cubans think

computers are the key to their future. Deciding who gets in, and who

does not, is the "most difficult task," according to Barcaz.

He says he is one of four people who determine what percentage of workers,

students and housewives the club accepts. Individuals from those categories

are then enrolled on a first-come first-served basis. Once they are

selected, "everything is completely free," says Barcaz.

Raul Varella,

a former student whose name has been changed, says the process is really

based on who you know or how much you pay. Varella, who runs in the

same informatico circle as Cuesta and Ferrer, said he was denied admittance

on his first attempt, but his father was friends with a teacher at the

club, who used his influence to get Varella in. After he completed his

first course, Varella again tried to enroll aboveboard and was denied.

"Through friendship it’s much easier," he says. He also

says business employees are given priority because their companies pay

in dollars to have them trained. According to Varella, it costs companies

$180 to enroll their employees in one four-month course.

"They

prioritize the admittance list according to business people like me

who work in an office," he says. "The company gives you money

and you take the classes. For individuals it’s free, but businesses

have to pay because you are getting skills."

The youth computer

clubs are not the government’s only efforts to get certain citizens

computer skills. The official journalists union handed out 150 computers

and home Internet accounts to distinguished members in 1999, including

installing phone lines if the reporters lacked them, says Aixa Hevia,

vice president of the union.

The state-sponsored

artist and writers union, known by the Spanish initials UNEAC, opened

up an Internet café for its members in October 2000. Tucked in

the back of a colonial palace off the Plaza de Armas, the café

gives writers access to the outside world, even if the connection is

slow. The five computers share one modem linked to a proxy server at

the Book Institute, the country’s largest publishing house. But

the café was bustling on a Saturday, with two people seated at

each computer, staring intently at emails or tapping furiously in Microsoft

Word as Simon and Garfunkel’s "Sound of Silence" –

downloaded off Napster – slipped around the room.

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

"Many

writers don’t have computers at home," says Joanna Ramirez,

20, one of the café administrators. "Writers can work on

their books here and then send them to other countries for interaction

and discourse." The 180 writers authorized to use the café

pay about 50 cents a month for membership. They have to book computer

time in advance in two- to three-hour blocks. For some the time isn’t

spent seeking critiques of their work, but rather emailing friends,

getting new versions of songs, or downloading software like PhotoShop.

A few members have computers and black market Internet accounts at home,

and one writer brings in his hard-drive, complete with songs downloaded

overnight from Napster – the embattled music sharing program –

so others in the café can hear and copy the songs. Another artist

uses the time to get world news not presented in the Cuban media, including

Castro’s nomination for the Nobel Peace Prize, which was submitted

in March 2001 by leftist Norwegian politician Hallgeir Langeland.

"We found

out Fidel was nominated for the Nobel Prize on the Univision Web site,"

says the writer, who asked not to be named, referring to the Spanish-language

broadcast group. "It was never announced here. That only goes around

by word of mouth."

"It’s

not like is used to be," says Ferrer in the musty Central Havana

apartment he shares with his mother. "Then we were in a bubble.

We used to see the world through tinted lenses. It was very difficult."

He is lounging against a Russian TV with a Marlboro in his hand, sunglasses

on his head, and gold bracelets on his dark wrists. The shutters are

closed and his mother is gone. It seems like a hacker’s room. Tacked

to the shelf above him is a sign that reads "no smoking."

Overhead, an inflatable silver alien dangles from a fluorescent light

bulb. The shelves are piled with bootleg CDs and grainy pictures of

Maria Carey and Pamela Anderson that had been downloaded and printed

out. Varella and Cuesta recline nearby. Ferrer’s "Frankenstein"

computer is on the desk. It’s a lonesome gray case – no keyboard,

no mouse, no monitor. A piece of white cardboard carefully cropped to

fit around the disk drive and start button covers the front of Ferrer’s

unfinished gateway to the world.

"We don’t

have to see what they want us to see," he says. "The world

is getting to know each other through the Internet. Everyone in the

world is the same as in Cuba."

Cuesta, however,

is more cautious in his assessment. "The state thinks the Internet

can change society," he says. "Tourism is more abundant and

is creating more of an effect though. People compare their lives to

the lives of outside people. That makes them think."

He leans back

in his chair against the closet door. Ferrer takes a drag of his cigarette,

fiddling with a bootleg Mariah Carey CD. He rests his eyes on Frankenstein

for more than a few seconds.

"You can’t

predict what’s going to happen," he says.

Back

to stories page