Four Writers

By Ezequiel Minaya

I missed him again, this

time by only ten minutes. For about four days now, I’ve been combing

Havana for Pedro Juan Gutierrez; a poet, novelist and journalist. I

want to talk to him about his writing, Cuban writers after the revolution

and censorship. But, above all else, I want to hear his thoughts on

exiled poet, Herberto Padilla.

|

Do

you think Gutierrez will want to talk about Herberto Padilla?

I ask as I prepare to leave.

I donŐt

know, Palacio Ruiz responds. WhatŐs

left to say?

|

I’ve stopped by underground

libraries, the apartments of independent journalists, and even the crowded

night-time hang outs lining El Malecon that Gutierrez wrote about in

his latest novel, Dirty Havana Trilogy. All I’ve got to show for

it is a messenger’s bag full of illegal, dissident writing, a dozen

new titles from the many Havana bookstores and more offers of sex than

I can afford.

Depending on whom you ask,

Trilogy — an international hit — may or may not be banned

in Cuba. Government officials have told me that it’s not widely

read in Cuba because it’s not a good book. It’s typical of

the Cuban writing so popular overseas, one writer’s union official

told me.

It has a dash of anti-Castro

— though Gutierrez never directly names him — and a lot of

sex, the official complained. But not just sex, he continued. Hot CUBAN

sex, he said in a mocking tone.

|

|

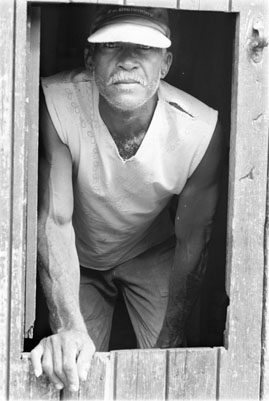

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

People on the fringes of

the state — reporters transmitting pieces critical of the government

to the United States via the internet, librarians operating out of their

apartments without state sanction, writers estranged from government-run

art institutions — have told me that some works are just not read

in Cuba. Censorship, that’s your word, one nervous writer said

to me; all I’m saying, he continued, is that somethings are just

not read in Cuba. Stop asking these questions, another writer advised,

you are going to get yourself or me in trouble.

Yes, Pedro Juan is in town,

I had been told several times over the last days. Yes he was here but

a day ago, a renegade librarian said. At an independent library in Miramar:

oh you missed him by a couple of hours. And now, at the independent

library Dulce Maria, just blocks from the official writer’s and

artist’s union, UNEAC, the caretakers — the married couple

Hector Palacio Ruiz and Gisela Delgado Sablon — say I was off the

trail by just ten minutes.

If you see Pedro Juan again,

tell him I just want a little of his time I plead. The three of us are

sitting in a small back room in the couple’s shabby apartment.

The room is the extent of Dulce Maria, and they say, a peaceful place

to live when books aren’t being tossed in the streets by soldiers.

Palacio Ruiz, in his loud,

booming voice says that Pedro Juan knows I am looking for him. He was

considering it says Palacio Ruiz, who has been in and out of jail because

of his own writing and Dulce Maria. He promises to put in a good word.

And as long as we are talking about favors, he says, could I do him

one? Could I, he asks, carry his latest collection of essays —

which included a letter he had written his wife during his latest stint

in jail — to the United States. I say yes, but please make sure

that Gutierrez gets my message. Sure, he says, but you make sure you

don’t get caught with these — he waves the thick sheaf of

papers.

Do you think Gutierrez will

want to talk about Herberto Padilla? I ask as I prepare to leave. I

don’t know Palacio Ruiz responds. What’s left to say?

Plenty. For starters, how

is the once international symbol of Cuban censorship remembered by notable

Cuban writers living on the island today. What does Padilla’s fall

from grace and subsequent exile mean to Cuban writers? Could it happen

again? How has Cuba changed?

On September 25, 2000, Herberto

Padilla, a visiting writer and professor at Auburn University in Alabama,

failed to show up for his literature class. His students went in search

of their professor and discovered him in his apartment—dead of

natural causes

|

Rivero

had not forgotten Padilla. No Cuban writer could.

But

Padilla is remembered less for his contributions to poetry than

for the chapter in the Cuban Revolution when the honeymoon between

Castro and his writers ended:El Caso Padilla.

|

Padilla, 68, had suffered

from heart problems. He had recently split from his wife, the writer

Belkis Cuza Male, who was living in New Jersey at the time, and had

just begun teaching at Auburn. Students barely knew the Cuban writer,

who immigrated to the United States in 1980.

But, at the time of

his death, Padilla was considered by many to be Cuba’s greatest

living poet.

His passing caused fewer

ripples in Cuba. Back in Havana, Raul Rivero -- a poet, journalist and

friend of Padilla -- remembered the news zipping by on television so

quickly that it took him a few minutes to fully understand.

Rivero tried to imagine

what the last years of Padilla’s life had been like in the United

States. Did Padilla — whose vocation as a poet immersed him in

Spanish — ever grow accustomed to hearing so much English? How

had Padilla handled the winters? Did he ever miss Cuba?

Rivero had not forgotten

Padilla. No Cuban writer could. But Padilla is remembered less for his

contributions to poetry than for the chapter in the Cuban Revolution

when the honeymoon between Castro and his writers ended: El Caso

Padilla.

In 1968, Padilla -- already

a respected poet and journalist — entered the annual literary contest

of the National Union of Writers and Artists (UNEAC). His entry, a collection

entitled Fuera del Juego, Out of the Game, was a scathing critique

of the government’s iron grip on intellectual life. It had only

been seven years since Castro’s remarks at a conference of intellectuals.

Having declared the Cuban revolution a socialist one earlier in the

year, Castro then wanted intellectuals to do their part for the cause.

He instructed : "What are the rights of writers and artists, be

they revolutionaries or not? Within the revolution all; against the

revolution nothing." That same year UNEAC was formed in imitation

of the Union of Soviet Writers.

Padilla chaffed under the

restrictions. In Out of the Game he wrote:

The poet! Kick him out!

He has no business here.

He doesn’t play the game.

He never gets excited

Or speaks out clearly.

He never even sees the miracles.

An international and independent

panel of judges awarded Padilla the nation’s highest poetry prize,

the Julian del Casal award, for the collection. The writer’s

union, however, declared Padilla’s poetry "ideologically outside

the principles of the Cuban revolution."

|

Cuza

Male now living in Texas told me that Castro came to their house

personally and said to Herberto, "You can go. Come back when

you are ready."

Padilla,

then 48-years-old, never saw Cuba again.

|

No action was taken against

Padilla until three years later, in 1971. Padilla was reading from his

work at the writer’s union, when authorities arrested the poet.

Among the tight-knit community of writers, the subsequent weeks of his

absence produced the inescapable question of the season in Havana —

"Where is Padilla?"

He reappeared a month later

and addressed many of the same people he stood before when he was detained.

This time, however, he read a scathing indictment of himself and many

other literary notables and friends. He condemned, among others, his

wife, the Cuza Male.

His public confession complete,

he disappeared again. But this time, in full view. Though released from

custody, Padilla would not be published for nearly a decade. He was

also forbidden to leave Cuba. Friends and family avoided the 39-year-old

writer and Cuza Male lived an internal exile.

Word of El Caso Padilla

spread around the world. And soon notable leftist intellectuals began

to retract their support for the revolution. A petition requesting the

release of Padilla was circulated and signed by, among many, Jean Paul

Sartre and Gabriel Garcia Marquez. The diminished prestige of one man

was becoming a costly loss of face for a country that — surrounded

by real and imagined enemies — could not afford to lose friends.

Finally, Castro decided that it was time to let Padilla go. Cuza Male

now living in Texas told me that Castro came to their house personally

and said to Herberto, "You can go. Come back when you are ready."

Padilla, then 48-years-old,

never saw Cuba again.

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

I Anton Arrufat

El Rehabilatado

Centro Havana is far-removed from the tranquility of El Vedado, home

of several state ministries, and the grandeur of Havana Viejo. This

section of Havana feels like a tough New York City neighborhood, with

a similar insularity, a sense that residents are caught, like satellites,

by the pull of the place. This is where Anton Arrufat, a national award

winning writer, has lived for much of his life, on the top floor of

a two story house that, like many other buildings in this part of town,

is a crumbling beauty.

Four men – ranging

in age from mid- 20’s to late 30’s – are hanging out

on the stoop of Arrufat’s house. Walking near them, I can smell

booze though it’s 10 a.m. They are arguing over the compensation

for a favor.

One of the younger guys

— a squat, barrel-chested man — insists, in slow drawn out

words, that the agreed price was a half bottle of rum.

One of the older men, skinny

and jumpy, his voice rising, disagrees. He distinctly remembers hearing

a full bottle and mira no venga con mierda, cono.

I ask them if this is the

home of Anton Arrufat. For a moment, they eye me, as if they don’t

understand the question.

|

I’m

surprised by the lavishness of Arrufat’s apartment. The

big rooms and high ceilings seem like they belong in New York’s

Dakota, renting out for thousands a month, as opposed to one of

Havana’s poorest neighborhoods.

|

One of them responds, yeah,

of course he lives here, everybody knows that. They look me over and

can tell I’m not Cuban. One of them decides to help the foreigner

out. You know -- what are you, Dominican? -- you know Dominicano that

Arrufat won a national award, don’t you?

Yeah, yeah, another one

chimes in, he also has a new book out, a book of essays. Cono, I’ve

got to get it, he adds.

At the appointed time, Arrufat

walks out onto his wrought-iron balcony and casually waves me upstairs.

I’m surprised by the

lavishness of Arrufat’s apartment. The big rooms and high ceilings

seem like they belong in New York’s Dakota, renting out for thousands

a month, as opposed to one of Havana’s poorest neighborhoods.

"This neighborhood

is very promiscuous, very crowded, very crime-ridden," he says,

adding that fame protects him. No one messes with ‘the writer.’

And, he’s clearly one.

The walls are lined with books shelves filled with every imaginable

title. Throughout the tidy, quiet apartment are several paintings and

sculptures. A small dog scampers between rooms, apparently pleased to

be hosting company.

Arrufat, a tall, solidly

built man with broad shoulders and soft middle, is quieter. His hair,

caught up in a short ponytail, is gray and he is wearing a plain white

T-shirt and shorts. At 66, he wears thick eyeglasses that barely soften

an intense gaze.

Besides the national literature

prize he also won the 2000 Alejo Carpentier prize for best novel,

for La Noche de Aguafiestas, Night of the Spoilsports. I was

introduced to him a day earlier at the writer’s union. "Here

is a true genius," the man said.

At the moment, Arrufat is

Cuba’s most celebrated writer. But it wasn’t always so.

In 1968, the same year Padilla

won the poetry award, Arrufat took top honors in the drama category

for his play Siete Contra Thebes, Seven Against Thebes. The play,

critical of the Marxist-Leninist regime, tripped censor alarms. The

writer’s union condemned Arrufat’s work as containing "conflictive

points in a political context that were not taken into account when

the winners were selected." To this day, the play has never been

staged in Cuba.

|

At

the moment, Arrufat is Cuba’s most celebrated writer.

But

it wasn’t always so.

|

And so, as with Padilla,

Arrufat was imprisoned in silence. But he stayed, refusing to budge

from the section of Havana he has called home since 1959 when he returned

to Cuba at the age of 24.

"When the revolution

triumphed I was living in the United States. I was living in New York,"

he says. But once Fidel rode into Havana, Arrufat, returned home to

a Cuba brimming with possibility.

"It was a moment of

great energy, of great happiness, of great vitality. It was like breaking

everything that had existed before; just destroying it. We didn’t

know if with good intentions or bad, if what should have been done had

actually been done or not, but that didn’t matter then, what mattered

was the enthusiasm of the moment, the magnitude of the time."

He became part of a group

of writers known as the Generation of ’50, that included: Pablo

Armando Fernandez, Cesar Lopez, Manual Diaz Martinez, Fayad Jamis, Herberto

Padilla, and on and on and on. "It had the feel of a family,"

he says.

The group established its

own identity by sweeping away the old literary regime. "We belonged

to a generation less transcendental," he says. "We used colloquial

language, conversational language. We used the language that was around

us. Metaphor was eliminated."

In illustrating the difference

between the writers of ’50 and the older writers, Arrufat quotes

– nearly sings really—a poem about fireflies by Lezama Lima.

He takes a poet’s pleasure in every word but "he never says

the word fire fly," Arrufat says. " I would have just said

fire fly."

TS Eliot, William Carlos Williams, Denise Levertov and the Beat poets

all influenced Arrufat’s generation. "We tried to write a

poetry whose musicality was destroyed by the poet. When a real musical

verse came to mind we busted it up, fragmented it, we made it rougher,

more arid, less musical, less melodic."

| One

writer, Ambrosio Fornet, called the late ’60’s, early

70’s the gray period, but Arrufat says now, "it was absolutely

black." |

The writers soon, however,

turned their critical eye to what was happening to the miracle that

had brought them home. The revolution began to change, repressing homosexuals

– many of whom were writers and artists like Arrufat – excluding

the religious and demanding complete adherence to the party line. Within

the revolution all; against the revolution nothing.

One writer, Ambrosio Fornet,

called the late ’60’s, early 70’s the gray period, but

Arrufat says now, "it was absolutely black."

It lasted about six or seven

years, Arrufat says, and during the time the government wanted writers

to copy rigid Soviet realism and produce proletariat morality tales.

They were also pushed to write children’s literature, to impart

to the youth the virtues of the revolution. But it was also an attempt,

in part, Arrufat tells me, to steer writers away from controversial

topics.

But it failed, Arrufat says,

with him, with Padilla and a few others. They challenged the miracle

and paid the price. "I was largely excluded for 14 years,"

Arrufat says. Forbidden to publish, Arrufat shelved books in a library.

But, Arrufat says, he was going to stay in Cuba.

But, Padilla, he remembers,

was struggling with the idea of leaving.

"He chose to leave,"

Arrufat says, without rancor of Padilla’s departure, "I don’t

criticize him for it. I think it’s fine. I chose to stay."

"His life was made

a little impossible, all those things that are done so a person will

go overseas, things that would give the reason to people who were accusing

him. So it was ‘look, he was an enemy, look how he ends up leaving.’"

Arrufat stayed and over

time, became "rehabilitated." Arrufat attributes the recovery

to the natural development of the nascent revolution. "Things just

went about changing."

In part, he says, the government

reconsidered its campaign against writers because it looked bad. "It

became a serious problem for the revolution." Many of Cuba’s

friends, Arrufat says, "were displeased."

With his reputation salvaged,

Arrufat, and others, including Armando, Lopez, Lezama, and Pinera, were

published again, but rarely overseas. Writers who wanted to do so had

to submit their manuscripts for review, and the government further discouraged

it by restricting writers’ abilities to accept dollars.

But publishing in Cuba changed

dramatically with the fall of the Soviet Bloc. Cuba’s GNP shrank

35 percent and the state slashed – along with everything else --

publishing budgets. The number of titles dropped by two-thirds over

a five-year period. Only 2,500 to 3,000 copies of any new edition were

printed. Many writers wanted out.

But, in a move as dramatic

as the legalization of the dollar in the 1990’s, writers were permitted

direct publishing contracts overseas. It is a move that many credit

with staving off a mass exodus. Arrufat is at the forefront of a wave

of Cuban writers who now publish internationally – once a crime.

Grijalbo-Maodadori, a Spanish publisher, released Arrufat’s Antologa

Personal, Personal Anthology, and also plans to offer La Noche

del Aguafiestas. Even Abel Prieto, Cuba’s current minister

of culture, publishes outside Cuba.

Though Arrufat makes it

clear that he has not lived outside Cuba since ‘59, he travels

often. He has spent up to three months visiting Spain and Mexico in

1993 he spent about five months visiting family in St. Paul, Minnesota.

I ask him if his life is

what Padilla could have had, had he stayed. "I think so,"

Arrufat says. "I think so."

But freedom has its limits.

I ask Arrufat about President Castro’s comments during the annual

Cuban book fair. Castro told visitors that there were no prohibited

books in Cuba.

Arrufat gives me a long,

steely gaze. "Well, here, I don’t think there are prohibited

books." He stops for a moment. "There are books that don’t

enter. There are books that don’t enter. That don’t enter."

He repeats the phrase softly, letting it trail off.

"Well, that’s

enough," he says suddenly. The interview is over.

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

My search for Pedro Juan

has hit rock bottom. I’ve just paid over $20 to two jinteros who

say they can find anybody in Havana. Yeah sure, we know the writer Pedro

Juan.

I met them at a jazz club.

We can show you the real Havana, they say with inviting smiles.

Pedro is the good-looking

one of the two. He is tall and an unbroken shade of dark brown. He has

a shaved head and big, sparking eyes. Manny is the brooder. He is heavy

set and wears a baseball cap low.

As we walk toward El Malecon,

Manny asks, Do you like girls? How about some real Cuban rum? How about

some coke?

A block away from the sea,

two police officers stop us. The muscular men wear neat brown uniforms,

shirts tucked in, tight over their broad shoulders and big arms. They

address Pedro and Manny with disdainful formality; come here comrades,

IDs comrades, stand still, comrades.

They ignore me and pull

Pedro and Manny several feet away. I’m told to wait. I can’t

hear what he is saying, but Manny is explaining the hell out of himself.

He is waving his hands with an urgent look on his face. Every once in

a while, after one of the officers asks a question, Manny just vigorously

shakes his head; no, no, no.

The officers approach me.

One of them, with a neatly trimmed mustache, addresses me. Sir, do you

know who you are hanging out with. My friends, I say and smile. That

man, he points to Manny, has been in jail for robbing tourists like

you.

No me diga, I say.

Now sir, he continues, have

these men sold you any tobacco or rum? Though he is out to stop a black

market transaction, he has stumbled across something better, I think

to myself; an American with a satchel full of dissident ramblings. Don’t

get caught with these, I can hear Palacio Ruiz say. At worst, I would

be arrested, questioned and deported but Palacio Ruiz said he would

catch hell again if anyone found his writing in the hands of an American

journalist.

|

Though

he is out to stop a black market transaction, he has stumbled

across something better, I think to myself; an American with a

satchel full of dissident ramblings.

Don’t

get caught with these, I can hear Palacio Ruiz say

|

No sir, no rum, no cigars,

I say. Can we check your bag, sir?

Of course, I say.

I do my best imitation of

a bumbling Yuma. Oh, I dropped my notebook, it’s a little dark

on this side of the sidewalk, oh, there goes all my change, well, I

guess you can’t really see inside the bag, let’s… what

do you say we cross the street to get under those streetlamps.

No, no sir, it’s fine,

the officer says. Have a good night.

Thank God Havana police

don’t carry flashlights, I think to myself. My heart is racing.

How does Hector live with this fear?

II

Raul Rivero:

Inxile

Neatly arranged on a small glass coffee table in the Central Havana

home of Raul Rivero -- an award winning poet and internationally acclaimed

journalist -- are small, framed photographs of various sizes. They form

a triangle, the tip of which is a picture of a young girl. The second

tier is two photos of teenagers. In all, there are about ten frames.

Mrs. Rivero, Raul’s second marriage, points to each picture and

says a name and then whether the person lives in Cuba or Miami.

| "The

same thing that is happening with the Cuban family," he says

pointing toward the photos around him, "is happening with the

literary Cuban family- there is division." |

He’s gone, she says

about her son. She’s gone, she says of Raul’s daughter from

an earlier marriage. There is no emotion in her voice; it’s as

if Miami is around the corner.

She agrees to wait with

me; Raul is running late. He’s, no doubt, working on a story, she

says. I sit in one of three rocking chairs in the small living room.

There are a few photographs on the walls – portraits of young people

bearing a resemblance to either Raul or his wife. There is a small television,

the small coffee table, a larger, round wooden table against the wall

and the rocking chairs. The floor is tiled in dingy linoleum.

We are joined by the silent,

and slightly hunched mother, of Raul. She slowly shuffles to a rocking

chair and sits down. Mrs. Rivero takes from me a small duffel bag filled

with medicine, vitamins, video cassettes of children’s television

programming and a digital video camera. Their friends in Miami sent

the care package.

We strike up a conversation.

We talk about the movie ‘Before Night Falls,’ the biography

of exiled Cuban writer Renaldo Arenas. Mrs. Rivero, who knew the writer,

remembers Arenas as a rude, blunt, moody character, who said whatever

was on his mind, no matter the consequences.

She says the actor who played

the lead caused a buzz in Central Havana when he moved into Arenas’

former home. She hears the actor is up for an Oscar. She recalls an

editorial in the few, slim pages of the official newspaper, Granma saying

that it would be a victory of politics and not art if he won the award.

Later that month, he loses.

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

The light from the open

balcony begins to dim. Over the next round of strong, syrupy coffee,

the talk shifts to politics. Mr. Rivero’s mother gets up, slowly

shakes her head and shuffles out of the room. Mrs. Rivero can’t

contain a small chuckle, nodding her head in the direction of her mother-in-law.

Raul finally comes home.

He is average height and stocky. He enters the living room, sees me,

smiles and walks forward, hand extended. The three flights up have left

the heavy-set smoker out of breath and speaking in short, clipped bursts.

He has one more thing to

do before his day is done, he says. It has something to do with his

journalist network. I’m sorry, he says, it can’t be helped.

In moments, I’m standing in the hallway, the door closed behind

me. The meeting is rescheduled.

A couple of days later Raul,

keeps the appointment. He’s relaxed but his face is still a light

shade of red. He sweeps his thinning blond hair with his hand often.

He is causally dressed, with the top buttons on his striped shirt open.

He is wearing shorts and slippers. Raul chain-smokes throughout the

conversation, whittling to the butt one Marlboro red after another.

We sit in rocking chairs,

facing the balcony and its view of Central Havana’s rooftops.

"The same thing that

is happening with the Cuban family," he says pointing toward the

photos around him, "is happening with the literary Cuban family-

there is division."

On one side of the divide

are writers that work with the government and collect all the perks:

travel, book signing parties, conferences, he says. Many of them were

once sanctioned, he says, during the gray period but have returned to

good graces with a vengeance.

"Pablo Armando Fernandez,

was sanctioned for about ten years because of the Padilla case, Anton

Arrufat, Cesar Lopez, all those people had problems. But they have returned

and are now in absolute harmony with the government."

| "We

spent many years in a very bad situation. I’m telling you,

we sold everything we had, everything, clothing, everything, because

we had nothing. I couldn’t publish." |

It was once that way for

Raul. "I, once upon at time, also made that pact. I moved in that

world, when I supported the government."

That was before he crossed

over to the other side of the divide.

Raul was one of the first

generation to get a degree in journalism from the University of Havana

after the triumph of the revolution. He eventually became a senior correspondent

for the state news agency.

He was also successful with

his art. In 1969, the writer’s union awarded him the David

award for his poem Papel De Hombre and in 1972 the Julian

Del Casal award for the book Poesia sobre la Tierra. He also

served as the right hand man of the first president of the writer’s

union, Nicholas Guillen.

But in 1989, Rivero, like

Padilla before him, grew disenchanted. He quit his position at the writer’s

union. And, in 1991, he completely broke with the government when he

joined nine other writers in composing an open letter to Castro, asking

for greater freedom of expression and the release of prisoners of conscience.

"When we signed the

letter there were ten of us. [Members of the group] began to leave immediately.

People were attacked. Maria [one of the signers] went to jail for two

years, reasons were found to arrest them.

"I wasn’t a member

of any political party so I was left here. But we got harassing phone

calls. People saying they were going to kill us in our sleep."

Raul says that, like Padilla, friends and family stopped visiting.

"We spent many years

in a very bad situation. I’m telling you, we sold everything we

had, everything, clothing, everything, because we had nothing. I couldn’t

publish."

| Of the

ten signers of the open letter, Rivero is the only one still left

in Cuba. "Why should I leave," he says, raising his voice,

indignant, when I ask why he decided to stay. "This is my country." |

Rivero says that crowds

of his neighbors would gather beneath his balcony yelling threats at

"the family of traitors." He says the yelling has stopped,

but his home still gets searched by police from time to time and his

phone is tapped.

"On television they

have a program called ‘round table." They have said on that

show that ‘Raul Rivero is a reactionary, counter-revolutionary

who receives money from the US interests section."

Last year, in a speech,

President Castro referred to Rivero as a drunk. Rivero, who had a drinking

problem, he admits, has been sober for years.

Of the ten signers of the

open letter, Rivero is the only one still left in Cuba. "Why should

I leave," he says, raising his voice, indignant, when I ask why

he decided to stay. "This is my country."

Raul is now an independent

journalist, and professional Inxile, a name he coined last year

in a Miami Herald article. Inxiles are, according to Rivero,

writers who still live in Cuba but openly oppose or at least are critical

of the government and as a result are kept from publishing and are often

harassed.

Arrufat was an Inxile, he

says, as was Lezama Lima and Pablo Armando. But the first Inxile was

Padilla, Rivero says. "Herberto was left completely alone, all

of us younger writers completely distanced ourselves from him. After

having much of the same things happen to me, I understand more than

ever [Padilla’s suffering]."

"You can’t call

people because you don’t know if they are scared to meet with you."

He gives the example of a friend - who Rivero asks not be named - who

still moves in official circles. If anyone was to find out that they

still spoke, he says, his friend would be at risk of losing his job

and status in the community. So, if they were ever to run into each

other in public, his friend would probably ignore Raul. Rivero wouldn’t

blame him.

"He’s not a bad

person. He just lives in Cuba," he says with a smile.

Rivero is openly harassed,

but other writers, he says, are kept in line by more subtle means --

a change from the open repression of the gray years. "Don’t

forget that here the state is the only employer, the one owner of everything.

"[The government] used

to insist that [writers] show publicly their loyalty to the country.

Now, if not that, at least try not to write in opposition, keep quiet,

in a very discrete way."

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

If a writer steps out of

line, Raul says, their requests to travel are suddenly denied, their

invitations to conferences and events stop coming. And in the case of

a writer’s continued and open defiance, Raul says, they lose their

jobs and are left to the ravages of poverty.

In 1994, in the midst of

his own precarious financial situation, Rivero was contacted by an exiled

Cuban journalist living in Spain, who commissioned two columns. That’s

when, Rauls says, the idea for an independent news service began to

form. A Miami contact gathered the financing for a web site and Cubapress

was born.

"We try to have people

from all over the country. It’s hard, because it’s hard to

get people in the remote provinces and it’s hard to train others.

At the moment we have 16 reporters."

Reporters dictate their

work over the phone or smuggle it overseas over black market internet

lines. Wages are around twenty-five dollars a month, which in Cuba,

Rivero says, is enough money to survive. In 1997 the French foundation,

Reporters Sans Frontières – honored Rivero and Cubapress

with its annual award. He was unable to attend the award ceremony, he

says, because of fears he would not be allowed back into Cuba.

He now knows how Padilla

felt, Rivero says. And he’s happy he was able to tell him before

Padilla’ death. One day, not long ago, Raul was on the phone with

an editor in Miami. After they were done talking business, the editor

said that she had somebody there who wanted to say hello. "It was

Herberto," Raul says.

"And I told Herberto

‘You’ve must of suffered a lot because it’s exactly how

much we are suffering now,’ but it must have been a lot worst for

him, because he didn’t have some one like Herberto Padilla, in

exile, to talk to him." He pauses and buries his chin in his hand.

Rivero talks a bit more.

But soon the seemingly boundless energy Rivero had at the beginning

of the interview wanes. Rivero lends me his only copy of his latest

poetry collection, which was published in Spain.

Outside, while waiting for

a taxi, I open Rivero’s book and begin to read at random. I stop

at the poem:

NATIONAL PRIDE

None of our officials are rich

None have estates, factories or companies

None have accounts in Swiss banks

Nor do they want them

and can’t help but be surprised.

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

III

Alberto Guerra

El Muerto

Even by the lofty standards

set by street after street of haunted, crumbling mansions in El Vedado,

UNEAC, the Cuban arts union on the corner of 17 and H, is impressive.

It is a peach-colored two-storied mansion with marble columns, ringed

by the thin bars of a black iron fence. Just off to the side of the

front entrance and down a small stone path, artists sit in the Huron

Blue Café, enjoying the rays of the mid-afternoon sun, quietly

talking at small tables. The porch is also peopled with groups talking

in undulating volume about painting, film, writing, art. There are young

people who could pass for New York bohos, and older conversationalists

who have a more rigid informality to them, as if they were on a corporate

picnic. This is the place that the World comes to when it want it’s

fix of Cuban Culture. Want a trio of folk musicians plucking out revolutionary

arrangements? An Afro-Cuban poet? A Cuban sculpture? This is where you

go.

Alberto Guerra, one of the

young stars of Cuban writing, prefers to stay away. He stays at home,

in the far-flung Havana neighborhood of Playa, seated in front of his

computer, chasing his dream, his foremost ambition, of being a great

writer.

The revolution’s victory

in ’59 led to the establishment of all of the now internationally

known cultural institutions in Cuba; Casa de las Americas, the

Cuban Institute of Cinematography (ICAIC), UNEAC, the National Ballet

of Cuba and many others. Castro vision for these institutions was made

clear; "Within the revolution all; against the revolution nothing

"

In 1976, Castro went a step

forward and decreed that "basic cultural centers" were to

be built in each of the 200 municipalities across Cuba. These

centers were: a museum, a cultural hall, a movie theater, an art gallery,

a bookstore, and a library.

It was in those culture

centers, especially the library, that Alberto Guerra, and many of the

young writers of his generation, first discovered literature and their

own talent. It was there that, during the international furor over Padilla,

he says, he studied, gaining a solid intellectual foundation.

But now, all Guerra wants

to do is write. He quit his job at UNEAC and has withdrawn his membership

in the communist party.

| "I

wanted to take a look at the situation in Cuba of the presence of

tourists. But I decided to look at it through the eyes of an average

Cuban." |

"I try to stay as distant

as I can so I can write. That’s to say I don’t engage

in a social life. Because the more of a social life, the less intellectual

intensity. So I stay here. Here in my neighborhood, in Reparto Flores,

in my house, writing," he says.

Guerra is 39, but can pass,

with ease, for someone ten years younger. He lives in a modest one bedroom

with his wife, who also defies her age and their teenage daughter. Guerra,

has a shaved head and is black.

He is proud of his heritage.

One of the few adornments on his wall is a portrait of one of his ancestors,

Tiburcio Naranjo, who was one of the first Afro-Cuban officers in the

Cuban military.

Guerra is very pleased that

I’ve come to speak to him. I read a story by Guerra in the UNEAC

literary magazine and saw in it a quality that I had not seen in any

of the other pieces in the union’s literary offers.

| The

narrator of El Muerto ends up gorging himself on all the

food and drink he can buy. Then, in a vivid scene, he throws it

all up. |

The story is called El

Muerto, The Dead Man. It is a muscular, taut story, that only uses

commas, no periods and tell the story of a young Cuban who assumes the

identity of tourist.

"I wanted to take a

look at the situation in Cuba of the presence of tourists. But I decided

to look at it through the eyes of an average Cuban."

The story opens with the

first person narrator in a hotel bathroom stall, counting Fula,

street slang for money:

Seated on the can, my

man, with the door nice and shut, I count the money and I can’t

believe it, my lord, I say to myself, I count it again, slowly, with

my pants at my ankles, as if I was wrapped up in the business of taking

a dump, so the employees and the curious suspect nothing, nine hundred

bucks is not a dream, I say to myself, real, constant, I count them

again,

The narrator then decides

to wear his new identity out on the town, carrying himself with the

mixture of stupidity and arrogance, according to the story, typical

of tourists. Soy una yuma, the narrator says to himself, to convince

himself that he is passing in his guise. Yuma is a derogatory

term for tourist.

As a tourist, Havana opens

up to the unnamed narrator. Women throw themselves at him, drawn to

him by his money. Bartenders, who would otherwise not look twice at

him, busy themselves, almost exclusively, to his comfort. Hotels, that

would do not permit Cubans to enter, open up to him and his money.

In a sense, with Guerra’s

short story, contemporary Cuban literature has come full circle. In

1950, Nicholas Guillen wrote an essay entitled Josephine Baker in

Cuba. The opening scene of the piece is a hand-wringing clerk of

the National hotel turning the singer away because of her dark-skin.

El Nacional was off

limits to black people and all other Cubans who couldn’t afford

the exorbitant prices. Guillen writes that the hotel might as well have

been a part of another country, dropped into the middle of Cuba. It

was not for Cubans.

| "I’m

happy when my work connects with someone," Guerra tells me.

|

Today, with the legalization

of the dollar and the increased dependency on tourism, the government

does not allow Cubans to step into hotels and other tourists areas.

Now, it’s not only black people who can’t go into hotels,

it’s all Cubans, who are subject the apartheid-like laws.

This is the environment

that Guerra wants to capture. The Havana overrun by young girls from

the country side, who come to work the street as jinteras. It

matters little that some of these women are college educated because

their jobs, if they have one, will only pay a fraction of what it costs

to survive. It’s an Havana where socialist ideals vanish as the

need for dollars becomes the ruling principle. The narrator of El Muerto

ends up gorging himself on all the food and drink he can buy. Then,

in a vivid scene, he throws it all up.

"I’m happy when

my work connects with someone," Guerra tells me.

His wife is giving him the

cold shoulder today, Guerra says. She’s upset that he has quit

his job at the writer’s union. But Guerra saw his position there

as little more than a distraction. He has to write. A black man has

to prove himself twice to measure up to standards in Cuba, he says.

Nobody, certainly not anyone in the union, is going to give him what

he wants, a place in the Cuban canon. He’s going to have to take

it.

He’s made progress.

In 1992 he won a major writing award. And he also accompanied Miguel

Barnett on a reading tour of Germany. Barnett, head of the culture ministry’s

Fundacion de Fernando Ortiz, and a major writer of an older generation,

thrilled Guerra when he mentioned that many years earlier he had gone

on the same tour with famed Mexican writer Juan Rulfo. "That’s

the first time I ever felt like a writer," Guerra says with a smile.

Guerra’s generation

is called the "the newest of the new." But even though his

generation is celebrated as the next big thing, there are already, he

says, a group of young twenty-somethings preparing themselves to charge

up the literary hill.

"We have yet to fully

arrive and already we’re being challenged," laughs Guerra.

We smoke cigarettes and

talk writing for hours.

But he doesn’t seem

to want to talk about Padilla.

Finally, he relents. Of

course, he says, he’s heard about Herberto Padilla. Who hasn’t?

Sure, it can happen again, he says. He seems reluctant to pursue the

topic.

"Look," he finally

says, "I just hope it doesn’t happen to me."

I’ve pretty much given

up on finding Pedro Juan but I decide to stop by Dulce Maria one last

time to see if my luck changes.

Hector is happy to see me.

After coffee and cigarettes I ask if he’s had a chance to speak

to Pedro Juan about seeing me.

Yes, he says, he was able

to meet with Pedro Juan one last time before he went back home to another

province. I’m sorry, Hector says, he did not want to talk to you.

He doesn’t want any

trouble, Hector says.

Back

to stories page