Cuban

Hip-Hop, Underground revolution

by Annelise

Wunderlich

Researcher: Eve Lotter

It's a late Friday afternoon

in downtown Havana and an old man in a worn-out tuxedo opens the doors

under the flickering green and red neon of Club Las Vegas. A poster

on the wall, its corners curling, advertises the usual cabaret fare:

live salsa, banana daiquiris, beautiful women. But the people standing

outside are not tourists looking for an exotic thrill. They are mostly

young, mostly black, and dressed in the latest styles from Fubu and

Tommy Hilfiger. And despite the $1 cover charge—steep for most

Cubans—the line to get in is long.

| "This

music is not for dancing. It's for listening," he says. "And

for Cubans, believe me, it takes a lot to keep us from dancing."

|

Inside, two young Afrocubans

appear on a small stage in the back; one tall and languid, the other

shorter and in constant motion. They wear baggy jeans, oversized T-shirts,

and sprinkle their songs with "c'mon now" and "awww'

ight." But while they admire American hip-hop style, MC Kokino

and MC Yosmel rap about a distinctly Cuban reality.

"It's time to break

the silence…this isn't what they teach in school…in search

of the American dream, Latinos suffer in the hands of others…"

A young man wearing a Chicago

Bulls jersey stands near the stage and waves his hand high in the air.

"This music is not for dancing. It's for listening," he says.

"And for Cubans, believe me, it takes a lot to keep us from dancing."

Kokino criss-crosses his

arms as he moves across the stage, and the crowd follows him, word for

word. Yosmel stands toward the back of the stage, his handsome face

impassive as he delivers a steady flow of verse. The audience is enrapt.

Anonimo Consejo—Anonymous Advice—is one of Cuba's top

rap groups, waiting for the next big break: a record contract and a

living wage to do what they love.

|

|

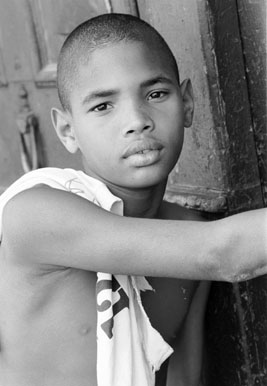

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

The two young men are not

the only ones. Three girls, decked out in bright tank tops and spandex,

sit on the sidelines and watch Kokino's every move. Yordanka, 20, Yaima

19, and Noiris 17, are cousins, and a year ago started their own rap

group, Explosion Femenina. So far, the only explosion has been

in their living rooms or at school talent shows, but that could change.

In a week, they will perform for the first time at Club Las Vegas. If

Cuba's top rap producer likes them, he'll groom them just as he has

Kokino and Yosmel.

Right now that producer—Pablo

Herrera—is in the DJ's booth, looking down at the two rappers.

"What you're seeing is Cuba's underground. I’m talking the

empowerment of youth as a battle spear for a more conscious society,"

he says in English so flawless that he's sure he lived another life

in Brooklyn. And he looks it—from the braids in his hair to the

New York attitude.

Herrera and a fellow representative

of the Young Communist Party put on the weekly Las Vegas hip-hop show.

With more than 250 rap groups in Havana alone, he chooses each Friday

night's line-up carefully. "I can't work with everybody, I'm not

a machine," he says with a shrug. "I mostly go with what I

like."

But even with Herrera’s

approval, the world for young rappers here is full of contradictions.

They believe in Cuba, but they're not ideologues—they just want

to make music from their own reality. Anonimo Consejo's lyrics

are edgy, but getting too edgy could end their careers. The

girls in Explosion Femenina try to be tough in the macho rap

scene, but rely on their sex appeal to get in the door. Each day is

a political and social balancing act.

Orishas, the only

Cuban rap group to make it big, traveled to Paris to perform in 1998

and stayed. Kokino and Yosmel look at them with both awe and disappointment.

Once abroad, Orishas made a hit record, but they did so by adding

Cuba’s beloved salsa and rumba beats to their music. Kokino and

Yosmel want to succeed by sticking purely to rap, but they've been at

it for four years and their parents—supportive up until now—are

beginning to talk about "real" jobs. All of these pressures

bear down on a passion that began as a hobby.

When they met eight years

ago, Kokino, then 13, and Yosmel, 17, were just kids looking for fun

on an island so depressed that scores of their countrymen were building

rafts out of everything from styrofoam to old tubes to take their chance

at sea. Yosmel and Kokino watched them from their homes in Cojímar,

a neighborhood on the outskirts of Havana where Ernest Hemingway once

lived. Back then it was Havana's sleepy beach town, but by the time

Yosmel and Kokino grew up, dilapidated Soviet-style high-rise apartment

buildings and cement block homes had taken over.

For relief from the dog

days of 1993, the two young men and their friends hung out at Alamar,

a sprawling housing complex nearby. The kids entertained themselves

in an empty pool improvising, break dancing, and listening hard to the

American music coming from antennas they rigged on their rooftops to

catch Miami radio stations. This is what they heard:

"’Cause I'm black

and I'm proud/ I'm ready and hyped plus I’m amped/Most of my heroes

don't appear on no stamps," rhymed Public Enemy in "Fight

the Power." Yosmel was hooked. "Their songs spoke to me in

a new way. There was nothing in Cuba that sounded like it."

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

Or anything that talked

about issues that Afrocubans had only begun to face. Instead, Cubans

have been taught to ignore race and the Revolution tried to blur color

lines by opening all professions, universities and government to Afrocubans.

Officially, race all but disappeared as a part of national identity.

But increasingly, race is

an issue in Cuba. If Afrocubans benefited most from the revolution,

they've also suffered the most during its crisis. Every Cuban needs

dollars to survive and the bulk of the easy money coming in remittances

goes to the white Cubans because it was their relatives who left early

on. Darker Cubans also face discrimination getting the island's best

jobs in the tourism industry. Skin color—despite the Revolution’s

best intentions—has once again become the marker of a class divide.

Kokino, Yosmel and others

in Cojímar felt it. "Because we are black, wear baggy pants

and have braids—which is strange in Cuba—on every block the

police ask for our identification cards. There is this perception that

all white people are saints and all blacks are delinquents."

Like disaffected youth everywhere,

they looked for role models that gave them a sense of pride. In school,

when Yosmel tried to talk about his African ancestry, teachers called

him "unpatriotic" for thinking of himself as something other

than Cuban. Yosmel turned to his mother to find out more about his African

roots, and before long, her stories became his lyrics: "In my poor

bed, I read my history/Memories of titans/Africans kicking out the Spanish."

She also taught him about

santeria, Cuba’s African-derived religion that has outlasted

any political regime. "In school they taught him about slavery,

but they didn’t go into depth," his mother says, standing

in the dirt yard in front of their small, wooden clapboard house. Lines

of laundry hang to dry in the hot sun. A single mother, she washes her

neighbor's clothes in exchange for a few extra pesos each month. Yosmel

weaves her lessons throughout songs like this one: "If you don't

know your history/ You won't know who you are/There’s a fortune

under your dark skin/The power is yours."

| If expats

like Abiodun served as historical guides, African Americans gave

Kokino and Yosmel their beat. |

He sought other teachers

as well. Cuba has long welcomed black American activists and intellectuals.

Yosmel and Kokino often stop by the house of Nehanda Abiodun, a Black

Panther living in exile. There, Abiodun gives them informal sessions

about African American history, poetry, and world politics. The messages

in their music, says the 54-year old American, come from being "born

in a revolutionary process where they were encouraged to ask questions

and challenge the status quo." It also comes from their daily lives:

"their parents, their experiences on the street growing up, what's

going on in the world."

If expats like Abiodun served

as historical guides, African Americans gave Kokino and Yosmel their

beat. "It was amazing to hear rappers from another country worried

about the same issues I was," Yosmel says. Rap artists like Common

Sense and Black Star have been travelling to Cuba since 1998 as part

of the Black August Collective, a group of African American activists

and musicians dedicated to promoting hip-hop culture globally.

Even when unsure about the

movement, the Cuban government welcomed American rappers because of

their support for the revolution, says Vera Abiodun, co-director of

the Brooklyn branch of the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, and part of

the Collective. Cuban youth responded to the rhythm, but also to the

visitors' obvious pride in being black. "We didn't know how huge

this would become in the beginning," she says.

Just as black Americans

did in the 1960s, Afrocubans in the 1990s embraced their African heritage.

"Every time that the police harass me, I don't feel like being

here anymore," Yosmel says. "When that happens, the first

place I think about is here," he touches an African amulet hanging

around his neck. "When I feel African, I don't feel black."

And for many young Afrocubans, rap music—not the syrupy lyrics

of salsa—validates the ancestry they've been taught to overlook.

Along with Che Guevara and

Jose Marti, Yosmel and Kokino admire Malcolm X, Mumia Abu Jamal, Nelson

Mandela and other black icons. They and thousands of other young Cubans

heard Mumia Abu Jamal’s son speak at an anti-imperialist rally

last year. And when Yosmel and Kokino talk about meeting rap artists

like Mos Def and dead prez, their faces beam. These members of the American

rap scene’s "underground" make social progress and black

empowerment a running theme in their lyrics. Rap has similarly linked

Kokino and Yosmel to a heritage that validates their existence –

and they hope their music will also improve it.

| "People

around here think we're a little crazy," he grins. "But

they love us anyway." |

Even in poverty, the frequent

foreign visitors and word-of-mouth popularity have given them a certain

cachet in Cojímar. "What bug crawled out of your hair and

ran around all night?" A middle-aged woman yells at Kokino as he

walks by her front porch, his long afro gently bobbing in the wind.

"People around here think we're a little crazy," he grins.

"But they love us anyway."

But you can't live on love.

That’s where Pablo Herrera comes in. A former professor who taught

English and hip hop culture at Havana University, Herrera is both a

devotee of black American culture and passionate about Cuba. He has

also emerged as Cuban rap’s main spokesperson internationally and

at home.

On an island where the government

controls just about everything, rap is no exception. A few years ago,

police regularly shut down hip-hop shows and labeled rap as "imperialist"

music. But Herrera and other hip-hop disciples waged a campaign to revamp

rap’s troublemaker image. Young writers like Ariel Fernandez published

numerous articles on rap in state-run newspapers and cultural journals,

while Herrera organized round-table discussions with government committees

about rap’s relevance for the Revolution. Herrera reminded the

old guard that the younger Cubans needed a voice—and rap music

was their expression of choice. "The purpose of hip-hop is serving

the country, not being an antagonistic tool," he says. "The

idea is to improve what is already in place."

His efforts were rewarded.

In 1998 Abel Prieto, the Minister of Culture, officially declared rap

"an authentic expression of cubanidad’ and began nominally

funding an annual rap festival. Even Fidel himself rapped along with

the group Doble Filo at the national baseball championship two

years ago.

Although officially accepted

rap is still in its infancy, Herrera estimates that Havana alone now

has more than 250 rap groups. He is the only producer with professional

equipment. Herrera, 34, works out of his sun-filled studio with a turn-table,

a mixer, a drum machine, a sampler, and cartons of classic Cuban LPs.

It may not seem like much, but by Cuban standards, it’s a soundman’s

paradise. "Since most music here is not really produced electronically,

there’s not many people who can do this," he says.

He produced Orishas,

Cuba’s only commercially successful rap group, before they left

the island and became famous. Now that Orisha’s remake of

Compay Segundo’s tune "Chanchan" can be heard

all over Havana, rap music is more popular that ever in Cuba. Herrera

hopes Anonimo Consejo can achieve the same stardom—without

defecting from la patria.

| A few

years ago, police regularly shut down hip-hop shows and labeled

rap as "imperialist" music. But Herrera and other hip-hop

disciples waged a campaign to revamp rap’s troublemaker image.

|

In a T-shirt with the words

"God is a DJ," Herrera shuffles through a stack of CDs and

smokes a cigarette while Yosmel and Kokino sit on his couch, intently

studying every page of an old Vibe magazine. "Yo, check this out,"

Herrera finds what he's looking for. "En la revolucion, cada

quien hace su parte." In the Revolution, everyone must do his

part. Fidel’s unmistakable voice loops back and repeats the phrase

again and again over a hard-driving beat. Herrera nods to Yosmel, who

takes his cue: "The solution is not leaving/New days will be here

soon/We deserve and want to always go forward/Solving problems is important

work." The music stops when a neighbor comes to the window and

tells Herrera that he has a phone call. Off he goes, dodging boys playing

baseball and dogs scrounging for food as he makes his way to the neighborhood

phone.

Herrera may not be the only

hip-hop promoter on the island, but rappers say he is the best connected

to the government. As a key member of the Asociacion Hermanos Saiz,

the youth branch of the Ministry of Culture, Herrera has rare access

to music clubs like Las Vegas. Any rapper who hopes to be seen at a

decent venue must first get the Association’s approval, and that

can only happen if their music is seen to serve the Revolution.

Herrera is also the unofficial

ambassador of Cuban hip-hop for the recent flood of foreign reporters,

musicians and record producers coming to the island in search of the

next big Cuban musical export. He discovered Yosmel and Kokino at the

first rap festival six years ago. "I work with them because their

music is really authentic," Herrera says. "I like their flow,

but what is really striking is what they say…so mind-boggling."

| "They

deserve a very good record deal, and they deserve to be working

at a studio every day making their music." But for now, when

their session is over, they still need to borrow a dollar to catch

a bus back home. |

Up to a point. Cuban rap—and

Anonimo Consejo is no exception—pushes the envelope, but

not so far that it offends the government. The duo has become a favorite

at state sponsored shows, warning young Cubans against the temptations

of American-style capitalism. In the song "Appearances are deceiving"

they rap, "Don't crush me, I'm staying here, don't push me, let

me live, I would give anything for my Cuba, I'm happy here." Their

nationalist pride recently helped them land a contract with a state-run

promotion company. All that means, though, is that their travel expenses

are covered when they tour the island and they receive a modest paycheck,

usually around 350 pesos each (US$ 17.50), after each major show. That

money doesn't go far in an economy increasingly dependent on U.S. dollars.

And it's getting harder to convince their parents that a rap career

is worthwhile.

Kokino quietly slips out

of the recording session at Herrera's studio and doesn't return all

afternoon. Later he says that he was upset and needed to cool off after

an argument he had with his mother that morning. "She says that

I'm a grown man now and she's tired of supporting me. She thinks that

I should get a real job," he says, twisting the end of a braid

between his fingers and looking at the ground. "She doesn't understand

that this is what I want to do—this is my job."

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

Five years ago, both Kokino

and Yosmel decided to forego Cuba's legendary free university education

and devote themselves to making music. Today, they both still live at

home with their mothers, depending on the state's meager ration cards

to eat. Herrera is trying to help them pay the bills. "They are

already the top group in the country," he says. "They deserve

a very good record deal, and they deserve to be working at a studio

every day making their music." But for now, when their session

is over, they still need to borrow a dollar to catch a bus back home.

Record deal or no, the girls

from Explosion Femenina would do almost anything to be in Anonimo

Consejo’s place. A faded portrait of Fidel smiles from the

dark walls of their tiny apartment in a rundown tenement in Central

Havana. The girls fill up the entire space as they crank up the volume

on their boom-box and rap about boy troubles over U.S. rapper Eminem's

hit song, "Real Slim Shady." Whatever they lack in technique

they make up for with sheer enthusiasm.

"When they first started

out, I thought it was just a fad," their mother says. "But

then they wouldn't let me watch my soap opera because they were practicing

all the time. We live like this," she squeezes her palms together,

"So I had no choice but to go next door to watch my show."

All the practicing has paid off. At next Friday's Las Vegas show, Herrera

will be listening.

On their rooftop, with the

sun setting over the maze of narrow streets below them, they practice

their one finished song. Yaima, born for the spotlight, undulates and

shimmies as all three harmonize about the hardships they've faced as

women rappers: "With my feminine appearance I've come to rival

you/If you want to compete, if you want to waste time trying to destroy

me/I'll get rowdy and impress you." The song is a flirtatious challenge

to the male rapper’s ego. "If you are a man, stop right there/Don’t

hide, kneel before me/Put your feet on the ground and come down from

the sky."

They know their music needs

a sharper edge to win over Herrera and they practice another song about

prostitutes. "We wrote this because so many guys we know assume

we're jinateras just because we like to look good," Yaima

explains. "Even though about 70 per cent of the girls we know do

it, we don't, and we're sick of them judging us."

Their most pressing worry

at the moment is how to pay for their outfits. "It will be about

$30 for each of us just to buy the clothes," Yaima complains. "It's

also about $25 for a producer to make us original background music.

That's impossible. We would have to give up going to the disco for about

three months if we wanted to come up with that." She laughs, but

the danger to their budding career as rap artists is real. Without the

right look or sound, they won't get much respect on stage. And without

dollars, those essential elements are out of reach.

| Their

most pressing worry at the moment is how to pay for their outfits.

"It will be about $30 for each of us just to buy the clothes,"

Yaima complains. |

The next Friday, outside

Club Las Vegas, the girls are giddy. They excitedly snap photos of one

another and different rapper friends, laughing to disguise their nervousness.

They huddle with Magia, one of the few women rappers in Havana, and

also their mentor. "Remember to pay attention to where you are

standing on stage. And sing in tune," she warns, rubbing their

backs in encouragement. Yaima frequently whispers to Papo Record, her

rapper boyfriend, and looks worriedly around the crowd gathered out

front. Papo, wearing a white Adidas headband and a spider tattoo, puts

his arm around her and kisses her forehead. Time to go in.

Santuario, a group

visiting from Venezuela, are the first on. Adorned with heavy gold chains,

gold-capped teeth, and designer labels, they clearly come from a different

economic situation than their Cuban hosts. Their manager films them

with an expensive video camera, and their background music is slickly

produced. Yaima, Noiris and Jordanka look on. Unable to afford the outfits

they wanted, they wear ordinary street clothes. "[Santuario]

are so amazing," Noiris says, biting her lip. "Do you really

think we are good enough to be up there after them?"

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

Good enough or not, DJ Ariel

soon calls out, "Explosion Femenina." The girls breathe deeply

and take the stage, looking very young and decidedly unglamorous. Spare

background beats boom out of the speakers, and they begin. Tentative

at first, it doesn't take Yaima long to get into the groove, and soon

all three are rapping and shaking their hips with confidence.

Their one song is over fast,

and the applause is friendly rather than deafening. Herrera takes Yaima

off to a corner. When she returns, her eyes are moist. She forces a

smile. "Pablo says that he is used to strong rappers," she

says. "He still sees us as very weak. He says that for our first

time we sounded good." But not good enough for Herrera to produce.

Nevertheless, the youth

branch of the Communist Party schedules the girls for an early appointment

to audition at the Ministry of Culture. They show up in their best clothes,

with boom box in hand, but no one is there to greet them. They wait

for an hour, and then leave. "It's always hard for rappers just

starting out," Yordanka says. "We just need to get some good

background music and keep practicing." But that will be difficult.

Yaima will leave Havana for a six-month stint as a cabaret dancer at

a resort in Trinidad, and Noiris and Yordanka have a lot of schoolwork.

"I love rap, but I am also really invested in my studies,"

says Yordanka, who wants to be an orthodontist.

For Pablo, there's only

one formula for success, in Cuba or anywhere. "Write great lyrics,

have dignity and be hard working," he says. But it takes more.

A week later, Club Las Vegas closes its Friday hip-hop show to make

room for a salsa band. "That's the way it goes in Cuba," Kokino

says, bitterness in his voice. "With salsa comes the money."

For now that leaves them

with Alamar, the first and last refuge of Cuban rap. Located on the

eastern side of Havana, on the other side of a long tunnel, Alamar is

home to more than 10,000 of Havana's poorest residents—most of

them black. Once billed as a shining example of communal living, the

giant housing complex was Fidel Castro's pet building project in the

1970s. Now, rows of shabby white buildings look out over the sea, far

from most jobs and services.

It is here in a giant empty

pool where Cuban rap began and continues. Every Friday night, Havana's

aspiring and already established rap groups pace the pool's concrete

steps and strain to be heard over a lone speaker in a corner. For only

five pesos, hip-hop fans can make the long trek out here to hear what

they won't hear on the radio: the music of their generation.

Yosmel and Kokino pay the

entrance fee like everyone else and mill with the crowd. Kokino sips

from a small bottle of rum and greets his friends with high-fives, while

Yosmel cuddles with his girlfriend off to the side of the pool. This

is their territory—everyone knows them, and no one cares much if

they have a record deal—here they are already famous.

| Despite

their lyrics about staying put in Cuba, Yosmel and Kokino want more. |

When it comes to time to

perform, the sound system fades and in the middle of one song the CD

skips, leaving them with no background music. Yosmel glares angrily

into the bright light coming from the DJ's booth. They start again,

but their energy is low. Next, a group of five young rappers come out

grabbing their crotches and doing a poor imitation of the American gangsta

poses they've seen on TV. Kokino cheers them on, but Yosmel sulks on

the sidelines. "I'm tired of this place. There are always problems,"

he mutters.

Despite their lyrics about

staying put in Cuba, Yosmel and Kokino want more. "We are waiting

around for an angel to come from abroad who recognizes our talent and

is willing to invest a lot of attention and money in our project,"

Kokino says. But celestial intervention moves slowly. Anonimo Consejo

has appeared on an US-produced compilation that has yet to be released,

and Kokino and Yosmel were featured in recent issues of Source and Vibe

magazines. But so far, none of that has translated into a deal or dollars.

"Sometimes I think

we’re supposed to live on hope alone," Kokino says, back at

his mother’s house where his bedroom is plastered with magazine

photos of NBA basketball stars and his favorite rap musicians from the

United States.

Then he hikes up his baggy

pants and goes outside to wait for a crowded bus to Herrera’s studio.

A couple of British hip-hop producers were supposed to swing by to hear

he and Yosmel lay down some beats.

Back

to stories page