Saving

the Cuban Soul

by Bret

Sigler

Researcher: Kelly Jackson Richardson

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

Oscar Leon Damien parts

the faded floral sheet that serves as a bedroom door and steps into

his blue shoebox of a living room. He sits in the wooden rocker, picks

up his bible and runs through notes in his head, making mental checks

to ensure that his sermon is in order.

A few blocks away Mario

Luis Ramos Madera rolls out of bed. He pulls an old but clean soccer

jersey over his well-built shoulders. He slips past his son, careful

not to wake him, and steps outside to have a smoke. He lights an unfiltered

Popular – Cuba’s national brand – and offers a bit of

tobacco to Eluggua, the orisha of opportunity.

These routines seem ordinary

enough, but Cuba’s religious revival has sparked fervent debates

that have been absent for decades. As Cubans again begin to consider

God – some for the first time – profound theological and social

questions arise. Who is God? Who needs him? And whose God are Cubans

likely to worship?

Pinar del Rio is a small

town in the interior of Cuba’s most important tobacco growing region.

The coastal sea breeze that cools Havana never arrives here, leaving

the dusty streets to bake in the Caribbean sun. UFO-shaped Soviet-era

water towers hover on the horizon, hoarding the province’s lifeblood,

as Pinarenos scurry along the shady side of Avenida Jose Marti,

the town’s only major thoroughfare. Locals are proud of their tobacco

and their baseball – the provincial team always challenging Santiago

de Cuba for the national title. But in Pinar del Rio, as in many other

towns, religious possibilities are stirring the spiritual. Here Catholics,

Evangelicals and Santeros vie for souls on an island where most religious

activity stopped when the Revolution took hold.

When Fidel Castro’s

Revolution triumphed in 1959, 80 percent of the population considered

themselves Catholic. Many Catholics also practiced Santeria, and Evangelical

Churches were just a blip on the holy radar. Before the Revolution,

many priests were anti-Batista and imprisoned and tortured for their

political views. But church bishops supported the dictator until the

end, and when Castro came to power, many of them fled to Miami with

their rich congregations. Still, Castro initially indicated tolerance,

if not support, of the church. In early 1959 he praised religious education

in state schools. But as Castro began his social reforms, the church’s

support for the Revolution faltered. By the end of the same year, many

young Catholics had denounced Castro and the Catholic Youth organization

published an article that said reform could be carried out without Communism.

This opposition made Castro

take a second look at religion’s role in his Revolution. Santeria

was still tolerated, but the government decided Catholicism belonged

to the conquistadors and the wealthy. Although Castro never outlawed

its practice outright, attending church became associated with antisocial

behavior the government placed hurdles in front of the openly religious.

They were barred from the Communist Party, the military and the university.

The Catholic Church kept up its pressure and in August 1960, less than

two years after Castro’s victory march through Havana, those bishops

who remained denounced Castro’s government. "Whoever condemns

a Revolution such as ours," Castro responded to the criticism,

"betrays Christ and would be capable of crucifying him again."

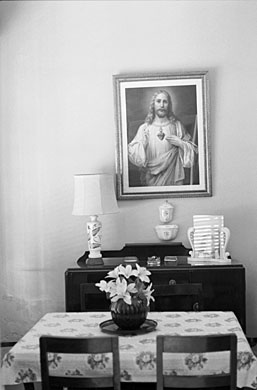

With Castro’s feelings

clear, if Christ remained in the hearts of some, practicing religion

became a clandestine affair. Religious education was banned from school

curriculum. Many churches shut down and fell into disrepair. Catholics

and Evangelicals met in small groups behind closed doors where the pious

erected makeshift altars in their living rooms. Most Cubans learned

to live without religion and to love the Revolution – religious

believers dropped from more than 70 percent of the population to less

than 30 percent according to official numbers.

| As Cubans

again begin to consider God – some for the first time –

profound theological and social questions arise. Who is God? Who

needs him? And whose God are Cubans likely to worship? |

But when the Revolution

lost the Soviet bloc in the late eighties, things changed. The country

entered the "special period." Times were tough – Soviet

subsidies were gone and Cubans were left to fend for themselves. While

much of the older generation persevered, the younger generation became

disheartened and began to look for salvation elsewhere. Sunday attendance

rose at the few remaining churches and new ones opened. Evangelical

groups expanded and university students formed religious groups. Religion

exploded and Castro retreated. He admitted in 1990 that the religious

had been treated unjustly, and in 1992, the once atheist government

declared itself a secular state and banned religious discrimination

with an amendment to its constitution. The official number of Evangelical

churches almost doubled to 1,666 between 1992 and 2000 (although Protestant

groups insist the number is much higher), and at least 55 denominations

now practice on the island. In 1998, 500,000 Cubans crowded into Havana’s

Plaza de la Revolución to attend Pope John Paul II’s first-ever

mass in Cuba. And a year later, a rally jointly organized by leaders

of 49 different Protestant churches drew 100,000 people to the same

plaza, with Castro himself seated in the first row.

But impacts of the old religious

policy remain. In 33 years without organized religion, many Cubans have

grown up with no notion of how it operates in other countries. Take

Reinaldo Arenado, an angst-filled 18-year old for example. He’s

a pinareno who has spent his whole life in Cuba’s near spiritual

void. He lives with his grandparents and his disabled father in the

center of town. When Arenado was ten, his mother left the island suddenly,

rowing for Florida. "She just kept telling me that she was going

over the big water, but I didn’t understand what she meant."

He hasn’t seen her since, and in her wake, Arenado has become an

introspective soul searcher. Although he isn’t religious, Arenado’s

intrigued by religious mysticism. He sits hunched in front of a small,

worn TV balanced on a rickety wooden bookshelf in the open-air living

room of his house – an old, colonial villa that the Revolution

has long since divided among several families – and pops a pirated

copy of the film Stigmata into the VCR.

| In

33 years without organized religion, many Cubans have grown up with

no notion of how it operates in other countries. |

"Where did you get

that?" I ask, knowing that the Exorcist-style religious

thriller is banned in Cuba.

"From a friend,"

he responds simply and quickly changes the subject. "This movie

is pure fantasy … It’s stupid," he says, but admits that

he’s never seen it. Arenado turns off the lights forcing the dingy

but ornately carved ceilings to fade into the darkness. As the FBI warning

flashes on the screen, the house falls silent, interrupted only by the

occasional dog barking in the distance.

He was right. The film is

stupid. It’s about a young American woman who becomes mysteriously

afflicted with the same wounds as the crucified Christ. The Vatican

responds by deploying an envoy of priests, comparable to the CIA in

their cunning and efficiency, to the woman’s home in Pittsburgh.

Arenado was mesmerized. With his deadpan stare illuminated by the rolling

credits he asked, "Is the Catholic Church really that powerful?"

"Our North

American friends want to know if there are any youth in the church,"

Damien calls out to his congregation at a youth meeting at his Assembly

of God church on a Tuesday night in March. The crowd erupts in affirmation.

At 60, Damien the Evangelical minister has aged gracefully with a slight

paunch and hair that is just starting to gray at the temples. His face

is dominated by a pair of thick, square glasses that constantly slide

down the bridge of his round nose. As always, he dons a pair of worn

dress slacks and one of his multi-colored guyavera shirts.

The church

is a concrete box that sits on a long, dusty road on the outskirts of

town where the scent of burning tobacco fields often fills the air.

A squat, blue steeple adorned with a small, wrought iron cross barely

pokes above the surrounding rooftops. The provincial baseball stadium

– a temple of a different sort – looms on the distant horizon.

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

Tonight, young

Christians from across the province have descended on Damien’s

church to discuss the church’s rural growth. Because Damien has

no car and little money to pay for other transportation, it’s a

rare opportunity to meet with members from outlying communities. The

group consists of mostly twenty-somethings, many with their young children

in tow, still yawning from the long day’s journey. The churchgoers

take special care to greet each other, one by one, with a handshake

or a hug.

The music starts

and Damien times his words to the beat of a salsa rendition of "May

God Always Bless You." A shabby three-piece band of drums, guitar

and synthesizer pounds out the tune. "I need somebody who can ride

a bike and who has enough faith to carry him along," he implores

the congregation – the microphone cord coiled in his left hand

in a style reminiscent of a fifties-era Vegas lounge singer. There is

new interest in the Assembly of God in San Cristobal, a nearby rural

community, and Damien is looking for someone to spread the good word.

An Evangelical

since his conversion at 14, Damien says that despite its limited resources,

his religious community has exploded. In the nineties alone, the Assembly

of God grew from 89 to more than 2,000 churches. But it isn’t just

Damien’s group. Mario Cesar Aguilar, the pastor at Catedral San

Rosendo, has also witnessed tremendous growth at his Catholic Church

on the other side of town. Aguilar says when he came to Pinar del Rio

in 1984 the church had less than 100 parishioners. Now he preaches to

a filled chapel every Sunday.

Rick Johnson,

the Assembly of God’s Caribbean Area Director in Florida, admits

that he doesn’t fully understand why religion is growing so fast

on the island, but says that it is "fulfilling something in Cubans’

lives that needs to be fulfilled." For Damien, it’s simple.

"Young people feel they are missing something," he said. "For

many years the government said there was no God. But God cannot be ignored

or denied."

And apparently,

neither can the pope. Religious attendance surged in Catholic and Evangelical

churches alike after his visit to the island in 1998. As of 2000, four

million Cubans – or 40 percent of the population – were baptized

Catholic. Official Protestant membership is also up to 500,000, although

many Evangelicals believe the true number to be much higher.

"It’s

not enough just to believe in God. You have to be consumed by him,"

said Ramon, a nineteen- year- old Baptist youth group organizer. His

reverend, Juan Carlos Rojas, agrees. Rojas is awed by the surge in young

membership at his church. "Cuban youth are an example to the world.

They truly are inspired."

|

"Cleanse

yourself of Satan. Accept Jehovah as your savior!"

But

who is Satan? It’s a slippery question for many pinarenos.

|

"You cannot

be a man of faith if you’re not obedient!" an assistant yells

out to Damien’s congregation. He is a tiny man leaning over a small,

wood-paneled podium. He waves his arms to forcefully emphasize each

word. The audience quickly turns their backs to the altar, kneels on

the floor and puts their heads face down on the rickety pews. Damien

watches from behind a ramshackle piano. "Cast Satan out!"

the man continues, his voice now becoming hoarse. The congregation begins

to speak in tongues – some barely whispering, others nearly shouting

in an almost rhythmic cadence. The smell of sweat fills the small temple.

"Cleanse yourself of Satan. Accept Jehovah as your savior!"

But who is

Satan? It’s a slippery question for many pinarenos. For Damien

and other Evangelicals, he is embodied almost everywhere – especially

in the Santeria ceremonies that take place in their very neighborhoods.

They say the worship of saints, or orishas as they are known in Santeria,

is a dangerous and powerful black magic not to be trifled with. And

the use of money in its ceremonies compounds the evil.

"Santeria

is the devil," Damien says plainly, his voice lowering as he pushes

his bifocals back up the bridge of his nose.

Damien’s

devil is just a few blocks away, locked up in Madera’s closet.

Here, behind a ramshackle wooden door in the corner of the house, Madera,

a Pinar del Rio native and one of only three bablaos in town, guards

his most powerful Santeria ceremonial tools: a goat skull attached to

a wooden stick, some bleached squirrel bones, a long, white candle mounted

on the skull of a cat. But Madera’s tools are no anomaly. For centuries,

Santeria has been ingrained in Cuban culture – and has transcended

traditional religious boundaries as Catholics and non-Catholics alike

have dabbled in the faith. "Santeria isn’t just a religion,"

said Dr. Margaret Crahan, a history professor at Hunter College in New

York, who has studied religion on the island for more than thirty years,

"it’s part of the Cuban identity."

Santeria is

a mixture of Catholic and Yoruban traditions that evolved when Spanish

fanaticism forced West African slaves to worship their orishas under

the guise of Catholic saints. By 1840, the majority of Cubans were of

African descent and Santeria had entered the mainstream.

"People

who lived in close proximity [to Santeros] began to adopt Santeria,"

Crahan said. "You can see how it permeated." And it continued

to permeate as blacks moved from the plantations to the cities, taking

their religion with them.

In modern times,

Madera says Santeria has been the darling faith of the Cuban people.

According to some estimates, as much as 70 percent of the population

practices some form of the tradition, many still blending it with the

Catholic faith. Castro routinely refers to Santeria as a point of pride

in Cuba’s afro-Caribbean culture, and ceremonies are often broadcast

on the national TV station. Now, however, some non-Santeros are openly

hostile.

| "Young

people feel they are missing something," he said. "For

many years the government said there was no God. But God cannot

be ignored or denied." |

"I have

to turn off the television almost every night," said Rojas. "It

disgusts me, with all the dancing. It’s the work of the occult.

It’s nothing more than folklore." Rojas, the son of a minister,

coordinates seven churches in the country’s fourth largest Baptist

mission. He and his family live in a small apartment above the mission’s

largest church, located in Pinar del Rio. He says that Santeria is widely

celebrated because so many people in the government practice the religion.

But for religious

leaders, popularity doesn’t equate legitimacy. To this day, many

Evangelical and Catholic authorities question whether Santeria is a

true religion. When the Pope visited Cuba in 1998 he said that traditional

Santero beliefs deserve respect but cannot be considered a "specific

religion." But it’s unlikely to disappear. Santeria is born

out of resistance and survival. Cubans have always flocked to Santeria

priests, or babalaos, during hard times to ease their weary bodies,

minds and souls; and the current climate of economic instability is

no exception. Madera says demand for his services has grown noticeably

in recent years. It’s a popularity that frustrates many Evangelicals.

"Santeria

and Christianity cannot exist together," said Ramon, a youth-group

organizer at the Baptist church. He is standing in front of the temple

and sweat gathers on his forehead as the Caribbean sun beats down. A

medley of vehicles sputters by, spewing black exhaust into the church.

"The bible says there aren’t any other gods but Him in the

heavens or on the earth."

But for Madera,

Santeria is more than just a religion – it’s his life. "The

Evangelicals," Madera says from his living room, "have a tremendous

struggle. They’re very self-righteous. They think they have the

answers to everything. Everyone keeps their religion like a son. But

Santeros don’t go out to criticize other religions."

"Yeah,"

pipes in Madera’s mother, an ancient woman with fiery red hair

and gray stubble on her chin, "those Evangelicals think they know

everything."

"Look,"

he adds, "if you feel badly – spiritually, psychologically

or physically – you come to me, we pray to the orishas, and you

feel better. How can healing be diabolical?" But as vocal as Cubans

can be about their beliefs, Madera says he keeps his opinions to himself.

"I have many Christian and Catholic friends," he says, "but

I don’t talk about religion.

|

"What

do you call that hat?" I ask.

"A

hat," he replies

|

Madera, his

mother, his wife and their son, a spry little boy who shares his mother’s

translucent green eyes, live in a two-roomed hovel at the end of a long,

narrow passageway that winds its way off the street. The Spartan abode

is a cool refuge from Pinar’s heat. Madera sees between seven and

eight clients per day but he says demand for his services has gradually

increased in recent years. Sometimes he goes to a Santero’s house

to perform a caracol or a limpia, the Santeria counseling and cleansing

ceremonies, but usually worshippers come to see him.

"Take

off your shoes and place your feet on the mat," Madera says to

a client as he prepares for caracol. They are in the back room of his

house. The sharp scent of urine fills the room – a reminder of

the small pig they’re raising in the corner. "It only costs

a few hundred pesos to buy one when they’re young," Madera

says, referring to the pig. After only a few months of eating whatever

scraps of food the family can muster, the piglet will soon be fat enough

to butcher and eat.

While the young

woman sits erect on a chair, her bare feet on the straw mat, Madera

puts on a red and black velvet beret that he reserves for such ceremonies.

"What

do you call that hat?" I ask.

"A hat,"

he replies, the corner of his mouth curling into a smile. But the headgear

is only a small part of the Madera’s arsenal of religious paraphernalia.

The dilapidated piano that juts out from the undersized kitchen is saddled

with religious shrines, or soperas, dedicated to a motley array of orishas

– Obbata, the god of power and health, Chango, the god of morality,

Yemaya the goddess of water.

Madera covers

his and the woman’s hands with white chalk and asks her to place

a bill on the pile of shells and stones in the center of the mat.The

monetary gift is a crucial element in Santeria ceremonies – and

one that Evangelicals criticize. "Money and religion don’t

mix," Damien says. "He can only say what he understands,"

Madera says, responding to the criticism. He says Santeria isn’t

a get-rich-quick scheme for babalaos. "Santeria is for everyone,"

he adds. Most of the clients’ money is used to buy the tobacco,

rum and sometimes animals that are offered to the orishas in various

ceremonies. "It’s not like in the United States," Madera

says. "If I were living there, I’d be a millionaire from all

the money Americans pay to those telephone psychics."

Madera repeatedly

throws the stones, shells and money onto the mat as he chants to the

orishas. The shells that land face-up are speaking; the ones that land

face down are not. He studies the patterns, and offers the woman his

advice. "You are generally healthy, but if you feel a pain in your

abdomen, go to the doctor – it could be your ovaries … You

are trustworthy and people are attracted to you. But be very careful

with some of them, especially lesbians, homosexuals and drunks."

Evangelicals’ criticisms don’t end with the Santeros. Relations

with the Catholics have also been strained. They view Catholicism as

a tired religion that relies on rehearsed prayers and arcane traditions

to bring salvation – and they’ve taken their critique to the

streets. In Havana, an Evangelical group recently passed out religious

pamphlets after Sunday mass in front of Santa Rita, one of the largest

churches in the country.

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

"I don’t

mind if they’re handing out pamphlets in front of the store or

in front of military housing or wherever," said Jaoquin Bello,

a layman volunteer for the church, his tight polo shirt straining to

contain his round belly, "but after our masses? No."

"We don’t

just count numbers and say ‘enough’," Father Aguilar

says back in Pinar, adding that Evangelicals are too preoccupied with

their official membership numbers. Aguilar, a chubby patriarch of a

man who begins most of his comments with "Well, my son," continues

on. "You have to evangelize, but we try not to do it with fear

or aggression. We try to educate with love and with God – and love

demands respect."

But respect

is often fleeting in Pinar’s churches and the town’s religious

leaders find themselves bickering over the particulars of faith. Aguilar

believes that communication is as imperative as boosting church memberships,

but he says the Evangelicals have been stubborn. The Catholic Church,

he says, has invited Damien and other Evangelical leaders to discuss

the state of religion in Pinar del Rio as well as the possibility of

coordinating small charity programs. The offer, he says, has been declined.

"Dialogue between the churches is very important," Aguilar

says leaning back in his rocking chair. "But it takes two sides.

We have demonstrated good faith … they have not. I hope that relations

improve."

That’s

unlikely for now. "There is a famous Cuban saying," Rojas,

the Baptist reverend says as his five-year-old son uses a sword to attack

stuffed animals at his feet, "A good wall makes a good neighbor."

Damien agrees. "I don’t want to criticize. There are many

Catholics that are very sincere in their religion – I was Catholic

before I found the Evangelicals when I was fourteen. But you can’t

erase history. The Inquisition was brutal," he says, referring

to the Catholic Church’s purging of Jews and other minorities in

fifteenth century Europe. "They’ve invited us to these meetings,

but we don’t go," he adds, sipping on a glass of watered-down

juice – a common beverage in these times of scarcity. Damien says

the Catholics’ history of global politicizing has damaged their

relationship with God. "The Catholics are diplomats. Politics and

religion shouldn’t be mixed."

But the squabbling

hasn’t deterred locals from practicing religion. And for some pinarenos,

the particulars of each church aren’t important. "I go to

the Baptist church often," says Mary Baez Iglesia, an elderly woman

with dyed, jet-black hair and pearly white dentures who lives around

the corner from Rojas’ church. When she hears that I’m investigating

religion, she disappears into her bedroom to dig up her old bible. It

takes her several minutes to locate the worn, paperback volume that

looks as old and dusty as her pre-Revolutionary house. Iglesia was raised

Catholic, but stopped practicing during the Revolution. In recent years,

however, religion has beckoned once again. "The Baptist church

is very beautiful," she says, as her non-religious husband grunts

under the worn bill of his baseball cap, "But I go to the Catholic

Church a lot too. I just like it, with all the singing and the mass."

Still, switching

churches isn’t always so easy. And with many Cubans practicing

religion for the first time, differing beliefs have created internal

family strife. Jeremiah, a thirty-something Assembly of God member who

is always flashing a broad smile, joined Damien’s church four years

ago along with his mother, two brothers, wife and daughter. Damien introduced

him as a convert; "he used to be a Santero … a drunk and a

Santero."

| "The

Baptist church is very beautiful," she says, as her non-religious

husband grunts under the worn bill of his baseball cap, "But

I go to the Catholic Church a lot too. I just like it, with all

the singing and the mass." |

Jeremiah’s

face drops slightly behind his smile. "Yeah, I used to be a Santero,

but that was all I knew. I didn’t know Christ and I didn’t

know it was diabolical." But he still has a brother and several

friends who are practicing Santeros. He says their religious differences

force them to have many discussions. "He talks and I listen and

then I talk and he listens," Jeremiah explained. "He hasn’t

converted yet, but I have faith in Jehovah."

Ramon, a nineteen-year-old

Baptist youth leader, says he joined the church two years ago after

he accepted God into his heart. But now, Ramon is having similar problems

with his secular family. "It’s difficult," he said with

a nervous smile, "but now, God is my life. The church is my life.

They don’t understand, but I’ve had a complete conversion."

Crahan says

Cubans, and especially Cuban youth, are joining churches in part because

they are feeling increasingly disenchanted by the government’s

shortcomings and are looking for fulfillment outside of the Revolution.

"Young people feel particularly betrayed," she says. "In

part, this is because the promises of the Revolution and its certainties

are obviously not seen to hold water with these individuals."

Young Ramon

doesn’t speak so pointedly about the Revolution, but in these times

of scarcity, and with basic medical supplies at a premium, he admits

that stories of God’s healing powers helped peak his interest in

the Baptist church. "There are many examples of God saving children,"

he said, remembering the story of a young boy who was suffering from

a degenerative muscular disease. The boy’s father, an unbeliever,

brought him to several doctors, to no avail. "But one day,"

Ramon said, "the boy accepted Jesus into his heart, and now he’s

better."

"My sister’s

in the military," a young newlywed told me in the back of Damien’s

church as she flipped through snapshots of her wedding. The woman, in

her early twenties, joined the church with her fiancee a year ago –

now they’re the only Christians in her family. She doesn’t

oppose the Revolution, but she says parts of it frustrate her. "You

can’t have any religion in the military and that’s been a

huge stress on our relationship."

So now, many

young Cubans are looking for promises and certainties in churches like

Rojas’. On most Sundays, the faithful are forced to jockey for

position outside his temple so they can peer in through the open-air

windows that flank the building. One churchgoer said it was only a matter

of time before more pinarenos started practicing religion. "After

the Revolution, el comandante said we couldn’t practice anymore.

But we kept pushing," he added, thrusting his elbow at an invisible

enemy.

Still, there’s

a flip side to Evangelical growth. Despite the influx of young people,

it’s been difficult for the churches in Pinar del Rio to recruit

middle-aged members. Damien says attracting men of 35 years or older

to the church has been especially daunting. "They have work or

they’re in the armed forces," he explains.

Crahan says

the older generation is simply coming from a different place. "These

are the people who participated in literacy campaigns, they received

health care and they do remember pre-Revolutionary Cuba," Crahan

said. Their feelings are "things have gone bad, but you can’t

blame the Revolution."

| Many

young Cubans are looking for promises and certainties in churches

like Rojas’. |

Maybe not.

But politics and religion are becoming inexorably intertwined. As Cubans

continue to scramble for basic necessities, they have become increasingly

dependent on churches to provide clothing, medicines and even food to

make up for the government’s shortcomings. Now religious leaders

find themselves walking a precarious line between providing spiritual

and physical fulfillment and angering Castro’s government.

Damien’s hands still tremble when he speaks about the state. He

suddenly looks all of his 60 years and uses hushed tones as he talks

about how difficult it has been for him to be a Christian in Cuba. Damien

and his wife first took over the church in Pinar del Rio in 1984 and

for several months they ate nothing but the rations of rice, beans and

five eggs they were allotted from the bodega each month. They avoided

the black market like the plague, refusing to supplement their diet

with additional eggs or meat – as many Cubans do – because

they felt they were under constant suspicion. "One day my wife

just put her head down on the table and cried out ‘This is so hard,

why are we doing this?’"

"Something

has to change here," Damien continues, his brow knotted in concern.

"Before, when the Soviets were around, we had everything, everyone

was for socialism. But now we have very little. It’s nothing for

you to offer us aspirin, but you can’t imagine how many people

come to me every week asking for aspirin or some other medicine."

And still, he says, it’s not completely safe to be a Christian.

"See that man over there?" Damien asks, pointing a careworn

finger at an elderly man at the back of the church, "He’s

in the police …You don’t know what it’s like to live

as a foreigner, as an enemy, in your own country."

And Damien

is tired of being the enemy. He laments over simple things. "You

know how difficult it is for me to go to Havana?" he asks, referring

to the travel expenses and the inability for most Cubans to stay in

a hotel. But even if he had the money, it doesn’t matter he says.

"You have to have relatives to stay with or the government is suspicious.

Even going to our beaches for a visit is impossible. They’re only

for the tourists now."

But Damien,

Madera and the others stop short of saying that their churches are hot

beds of dissident organizing. "Santeria is a religion of peace

and healing," Madera says. "It can’t be about rebellion."

"We don’t

know if there are dissidents in the church because we don’t ask,"

Damien whispered one afternoon from inside his darkened, empty temple.

"That’s very dangerous. We don’t mix politics with religion."

Rojas agrees. "There’s no room for anything but the bible

in my church."

He may be right,

and many Evangelicals believe that’s how the government wants to

keep it. To accommodate their growing communities, Rojas and Damien

have solicited construction permits from the government to build new

temples for their respective churches. Both have been rejected. The

state routinely denies such permits, forcing many groups to open informal

facilities in members’ houses. Many Evangelicals see these denials

as a way for the government to control religious growth on the island.

"Look

at us, we have to hold classes outside," Rojas says from the small

vacant lot behind his church where he someday hopes to build a new temple.

Small groups of Sunday school students sat scattered around the yard

discussing the day’s gospel – some huddled beneath an ancient

tree while others leaned against the whitewashed wall of a makeshift

garage.

And space is

even tighter at the Assembly of God. Damien lives with his wife in a

tiny apartment above the church. The couple hopes to convert their small

storage area into a much needed temple addition. They’re still

waiting for a permit. "Here, there’s only one employee, the

government," Damien said. "In one way or another, it always

comes back to the government."

To deal with

space shortages, Damien says his church has opened "preaching points"

in members’ houses throughout the province. The Assembly of God

has established 890 preaching points across the island. But still, Damien

says officials will shut meetings down if more than 15 people are present.

Now the church constantly rotates the meetings between different living

rooms. Johnson, the church’s Caribbean director, says the government

also tries to exert control over his church by grossly misrepresenting

membership to downplay its impact on the island. Official numbers report

83,000 baptized Assembly of God members in Cuba, but Johnson says there

are tens of thousands more practitioners.

Father Aguilar also feels discrimination despite Cuba having become

a lay state. "The method of oppression has just changed,"

Aguilar says. "Now the government uses more psychological repression

than physical," he adds, referring to government policies that

still restrict complete religious freedom. The state routinely shuts

down religious meetings in homes, for example, citing laws that limit

the number of people allowed to congregate in private locations. "Perhaps

it’s changed in the sense that people can breathe easier, but it’s

still difficult."

Difficult or

not, Cuba’s Catholic Church isn’t the same organization that

involved itself with the Latin American Revolutionary movements of the

seventies and eighties. Although the majority of priests supported Castro’s

Revolution, much of the hierarchy was in line with Batista and fled

the island in 1959. "The churches keep their distance from dissidents,"

Crahan said. She says liberation theology hasn’t taken hold in

Cuba. Crahan remembers a recent conversation with a Cuban; "I asked

him about liberation theology, and he responded ‘What do we need

that for? We’ve already had our Revolution.’"

| People

think there are only two options," he says, holding up his

pinkie and index finger. "To be for the Revolution or against

the Revolution. But there’s a third way," he added while

extending his thumb, "to be a Christian." |

Still, the

Evangelicals have organized several events to spread God’s word.

Last year the Assembly of God and other churches held an Evangelical

religious rally in Pinar del Rio’s nearby baseball stadium. But

the Catholics, Damien said, weren’t invited. The gathering came

on the heels of a Protestant rally in Havana that drew more than 100,000

Cubans. "If the Pope could do it, so could we," Damien said

with a chuckle, referring to the 1998 papal mass that drew hundreds

of thousands of Cubans. "We had to prove that we weren’t inferior."

Despite prohibiting private gatherings of more than 15 worshippers,

the government has permitted the occasional release valves of religious

fervor.

Many North

American churches have shown their support by establishing relationships

with their Cuban counterparts to help them cope with scarcity on the

island. Pastors for Peace has been delivering "friendshipments"

to Cuba since 1992. In Havana, two American school buses from Pastors

for Peace San Francisco were recently parked in front of a Baptist church.

They were covered with social-political statements painted in bright,

multi-colored letters written in English: "This bus is going to

Cuba with medicine in defiance of the unjust US created embargo on Cuba."

And on the back bumper, "Be a real Revolutionary … practice

your faith."

Cross-border

relationships have allowed many churches to provide much needed clothing

and medicine to some Cubans, and in these times of scarcity, foreign

donations can be a boon for local memberships. "If one minister

has a car or a school, he’ll be more popular," Crahan said.

"Of course economics influence membership," says Rojas. "If

you have a bible to read and there are fans around to keep you cool,

you will enjoy church more." But he’s quick to note that people

are drawn to modest temples as well. "Look at us," he says,

"we have to hold classes outside."

Even in Pinar,

some religious leaders have traveled to the United States to foster

these relationships and speak about conditions in Cuba. Rojas has visited

several times, and has been invited twice to First Baptist Church in

Archdale, North Carolina to preach and to receive "love offerings"

of medicines, bibles and other necessities to distribute to his congregation.

Although Rojas still has several friends at First Baptist, he was shocked

by the state of the Baptist faith in the United States. "They haven’t

lost their vision," he says, "But there is also great weakness.

People work too much. They worry too much. Materialism has corrupted

man."

"He’s

just a whole lot more staunch in his beliefs," says Gary Green,

a First Baptist Church member in Archdale, adding that he was a bit

ashamed that his brethren drank and smoked in Rojas’ presence.

Damien has

also fostered relationships abroad. He has visited Assembly of God Churches

in Los Angeles and Las Vegas ("People aren’t meant to live

in those conditions," he said, commenting on the desert heat),

and Father Aguilar has spent many months in Miami – most of them

while recovering from knee surgery.

But despite

religion’s ever-changing role in Cuba – and it’s ability

to provide for some where the government cannot – it’s difficult

to know if churches will prove to be a major point of resistance against

Castro. "I’m not going to predict what is going to happen,"

Crahan says. "Churches are stepping in to fill that void within

their means. Their overseas connections and access to money make them

prime candidates to do so."

In Cuba politics

are life, but for Damien there are alternatives. "People think

there are only two options," he says, holding up his pinkie and

index finger. "To be for the Revolution or against the Revolution.

But there’s a third way," he added while extending his thumb,

"to be a Christian."

And for Jeremiah,

that’s getting easier every day. "Before, it was impossible

to be Christian – you couldn’t get a job, people made fun

of you," he said. But now, Jeremiah greets people in his neighborhood

with "May God bless you," the familiar Christian salutation.

"It’s so much better. People ask me ‘Are you a Christian?’

… ‘So am I!’" Jeremiah isn’t alone. He and

the others hold great hopes for the future of their churches as religion

is reborn in Pinar del Rio.

"Mass

is about to start," says a plump man donning a Catedral San Rosendo

T-shirt in front of Father Aguilar’s church. He’s waving the

faithful into the colonial temple, now just a shell of its former grandeur,

floating on a sea of brown grass.

A few blocks

away, Madera thinks about how he will one day pass the knowledge of

the orishas on to his son, like his uncle did to him. He is comforted

in knowing that the legacy – and the faith – will continue.

Meanwhile Damien

remembers his brothers that have left Cuba for the United States in

the hopes that they could practice their faith in peace. He thinks about

them, and about his experiences at home, and he knows he is where he

belongs.

Back inside

Aguilar’s church, neighbors greet each other with handshakes and

kisses. A young mother shows off her newborn to the congregation under

the watchful eyes of the wax saints enshrined throughout the temple.

Aguilar stands in front of the Cuban flag on the altar and looks out

on his community.

And Rojas sits

at the head of the table to leads his family in grace, thinking about

the message of his last sermon: Christ doesn’t control our lives,

he only tries to direct us, like a bridle does a horse.

Back

to stories page