Revolution

is a Moment

By Olga

R. Rodríguez

Reseracher: Osvaldo Gomez

I knew I had arrived at

my destination when I saw the hammer and sickle emblem outside the door.

My walk there had not been through the Florence you see on postcards.

Few corner stores, ice cream or flower shops operated on this side of

the river. I was there to meet Alessandro Leoni, a founding member of

the Communist Refoundation Party, a faction of the Italian Communist

Party that survived the party’s break up in 1991. Tall and slim

with a bushy mustache discolored by years of smoking, Leoni opened the

door to an office filled with posters of Lenin, Stalin, Che Guevara,

Antonio Gramsci and smoke. He lit cigarette after cigarette as he spoke

of solidarity, of equality, of the rights of the poor. For more than

four hours, he talked Communism, Cuba, Mexico’s social problems.

The smoke swirled around us.

|

|

photo

by Ana Campoy

Rosa Maria

Almendros in her Havana apartment.

|

Five years later, I remembered

that episode as I walked down the Malecón in the sweltering sun

of Havana. Flanked by the calm and clear Caribbean ocean and the old,

deafening cars, I wondered whether foreigners who had moved to the island

during the 1960s remained as supportive of the Cuban revolution as Leoni

was when we spoke in 1996.

I first visited Rosa Maria

Almendros, a Spanish contemporary of Leoni who moved to Cuba after the

triumph of the 1959 revolution.

"It was a dream come

true," Almendros, sitting in her Havana apartment, says. "We

knew with Castro in power it wouldn’t take long before a just society

would be created."

Almendros and her husband,

Edmundo Desnoes, a Cuban journalist and author, watched the film clips

of Fidel Castro, dressed in his now legendary olive-green combat fatigue

and with his rifle tossed over his shoulder, as he marched triumphantly

through the streets of Havana on January 8, 1959. Cubans filled the

streets to welcome the man who promised to fulfill the dreams of Jose

Martí, the father of Cuba’s independence. More than 1,300

miles away in New York City, Maria Rosa Almendros joined the celebration.

Already, they had followed

and raised funds for the 26th of July Movement, Castro’s rebels.

It didn’t take long -twelve months to be exact- before Almendros

and her husband moved to Havana. The years that followed, Almendros

says, fulfilled expectations. The barbudos, the young, rugged revolutionaries

heroes of the Cuban struggle, walked the streets of Havana and lived

and worked among the Cuban people. Cubans packed the Plaza de la Revolución

to listen to a young, passionate and defiant Castro challenge the United

States. Legends like Che Guevara and others were being made and revolution

was the muse of Latin American intellectuals, poets and painters. Sympathetic

foreigners watched the island transforming and many became part of it.

"In Spain we lost a

battle but in Cuba we won the war," says Almendros, whose father

fought in the Spanish Civil War against Franco. "There was a lot

of hope for what Cuba could accomplish. It was a revolution based on

faith."

Cuba and Castro enticed

foreigners, including Almendros, to leave comfortable lives and come

to the island to cut cane, teach reading and writing, to replace doctors

and university professors and for some to work in the new government.

The young, enthusiastic idealists came from the United States and all

over Latin America to experience revolution. Hope for the future became

the essence of Cuban life and their lives.

| "The

1960s were a time when anything was possible and when other Latin

American countries were looking toward Cuba for inspiration,"

Almendros remembers as she peeks through a pair of glasses with

the right lens cracked right through the middle. |

Forty years later few foreigners

remain. Some defend the revolution with conviction that has lasted more

than four decades. The island, they say, will remain true to its revolutionary

values, even in the face of tourism and the dollarization of the economy.

Others have no where else to go and find themselves stuck on an island

frozen in time. For them, the revolution has been reduced to a memory.

But not for Almendros. At

71, her support for Castro’s revolution is unconditional. When

I step into her apartment, she’s sitting in a rocking chair two

sizes too big, she’s barely five feet tall, pale and wears bright

red lipstick. Her brown shoulder-length hair, without a trace of gray,

matches her long, flowing black, white and brown tye-dye dress. "The

1960s were a time when anything was possible and when other Latin American

countries were looking toward Cuba for inspiration," Almendros

remembers as she peeks through a pair of glasses with the right lens

cracked right through the middle. "I am happy here. I have everything

I need," she says. "I don’t worry about anything. I have

never been materialistic."

Staying has not been easy.

Her apartment is in a decaying building with an elevator that rarely

works and a set of stairs so dark you have to feel with your feet before

you take a step. Inside, the walls are filled with artwork and crafts

from the different countries she has visited. She has old books piled

high in the corner of a terrace where she likes to eat breakfast and

watch the waves of the Caribbean ocean crash against the Malecón.

In bookshelves scattered around the house she keeps books about museums,

painters, art history and the books by the Latin American authors she

has met. She shares her phone line with a neighbor who can’t afford

to pay for her own and the artwork comes in handy. "I had to sell

a painting to be able to fix the leakage on the roof," she says.

Then quickly explains,

"The government does not have the resources to take care of things

like that."

Some of the paintings and

books are from renowned Cuban and Latin American artists she met during

the 1960s when she worked as director of information at Casa de Las

Américas, Cuba’s main cultural center and publishing

house. It was founded in 1959 by Haydee Santamaria, one of two women

arrested with Castro during the Moncada attack, the 1953 failed attempt

by Castro’s rebel movement to start an armed uprising against Fulgencio

Batista.

|

Even

now, Almendros’s faith in the revolution remains.

"This

has been a profound revolution, but not a bloody or cruel one."

|

Casa de las Américas

became the headquarters of leftists, intellectuals and artists who,

during the 1960s, visited the island often hoping to duplicate the Cuban

revolution in their countries. Many of them, Almendros points out, failed

to accomplish what Castro achieved. But she’s met them all. Roque

Dalton, the Salvadorian poet and founder of the Frente Farabundo

Martí para la Liberación Nacional or FMLN, the leftist

guerilla movement, became a legend after his own comrades killed him

in 1975. Victor Jara, a Chilean poet and singer was killed by Augusto

Pinochet after the1973 coup that ousted Salvador Allende, the socialist

president.

"Victor taught me how

to sign with my hands," Almendros says. "We would be in different

corners of a room and we would talk by signaling. Did you know they

smashed his hand before they killed him?" she asks without expecting

an answer.

Even though Almendros and

her husband aided Castro’s rebel movement she did not feel worthy

of the revolution. "We felt we did not deserve to come back,"

she says. "We had done very little to help." But when they

heard rumors that Cuba was going to be invaded by the United States

she willingly left her marketing job on Fifth Avenue to defend the revolution.

By the time the United States

backed anti-Castro Cuban exiles landed at the Bay of Pigs, Almendros

and her husband were there mobilized and ready. "We were in our

posts," she says. Almendros worked for Casa de Las Américas,

her husband at the Ministry of Education. Although they never saw any

combat, they stayed. "I felt I had done something to contribute,"

she says. More then she could in New York, where she found people caught

up in "fashion trends, materialism and shallowness."

Even now, Almendros’s

faith in the revolution remains. "This has been a profound revolution,

but not a bloody or cruel one." Moreover, it changed more than

her life. In El Rosario, a village in Oriente Province, she witnessed

a whole town go from a place where people were infested with parasites

to a place that Fidel Castro would call "an example for others

to follow."

It was while at El Rosario

that Almendros met Fidel Castro, a man she describes as "a mortal

protected by the gods."

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

"I remember seeing

his jeep approach and feeling like I was going to faint," she says

putting her hands on her face. "He had come to get a report about

the progress in our town and I was so nervous that I would not remember

all the details. I panicked."

She had met important men

before. She had eaten with Che Guevara with Salvador Allende and countless

personalities of the Latin American literary world, but meeting Fidel

was different.

"I was shaking like

a leaf," she says. "He asked about the three tractors that

he had sent on such and such a date in 1970. That’s when I realized

that the myth about his memory was a reality."

"He turned to me and

said and ‘you little girl?’" she laughs. "I was

41 at the time. But I guess my height has always made me look a bit

younger."

Castro asked what she was

doing there. "I said I was doing social work. But I said it with

a Spanish accent and he noticed. He talked with Spanish accent also

and we laughed." He left without asking any questions but told

Almendros she had done great work and should be proud of it. "I

was so relieved he had not even asked any questions that I did not even

think about just having met the Comandante en Jefe. When he left it

was as if I had cut burnt cane all day, as if someone had just beat

me up."

Almendros says the only

time her faith faultered was in the 1960s when some of her homosexual

friends were persecuted. "This was hard on people," she says

but prefers not to talk about specific cases. "You have to understand,

the government recognized its mistake before it was too late."

But the 60s are long gone

and struggling to survive has endured. The challenge now is to maintain

a balance between socialism and the capitalist ventures that fund the

revolutionary ideals.

| It’s

hard to imagine a bright future for the Cuban revolution when you

see a Havana trapped in a time warp. Everything seems a contradiction.

|

So far the biggest change

has been the legalization of dollars and tourism. For Almendros dollars

and tourists are necessary evils. "When the government first announced

they were bringing in more tourists the first thing I thought was how

this was going to rot Cuban society," she says. "It makes

me remember Pancho Villa (the Mexican revolutionary) when he said ‘be

afraid of the dollars and not the bullets.’" She thinks for

a second, "I know Fidel will not let that happen."

She pulls out her album

and proudly shows me her collection of photos of the Comandante en

Jefe she keeps. These memories, she says, make her grateful to have

had experienced a revolution that will continue, "Even when Fidel

is no longer among us."

If only that optimism translated

into reality, I thought after I left Almendros. It’s hard to imagine

a bright future for the Cuban revolution when you see a Havana trapped

in a time warp. Everything seems a contradiction. Cubans come up to

me and start a friendly conversation that ends in a business transaction

of some kind; colonial building in decay but that still look royal,

and the deafening Studebakers, Chevys, Fords and Cadillacs from the

40s and 50s move among the modern cars that carry a tourist license

plate. I think of Almendros reference to Pancho Villa and I wonder if

he wasn’t right. Dollars, and not bullets, will bring change to

an island struggling to hold on to a 40-year ideal.

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

For Jane McManus, an American

who moved to Cuba in 1969, the island’s contradictions are proof

that the revolution is coming to an end. McManus, 80, moved to Cuba

early on. Disenchanted with the U.S. left, she wanted to live in a socialist

system. The 32-year experience, however, has been bittersweet.

"When I first arrived

I worked very hard as you always do when you are enthusiastic about

something," says McManus, a lanky woman with short white hair and

piercing blue eyes. "But that kind of enthusiasm no longer exists.

In the late 60s, people would do anything for their government, not

anymore. You can’t sustain it. Revolution is a moment."

The daughter of an IBM executive,

McManus grew up in an upper middle class household in New England. Her

father voted Republican and her mother became politically active late

in life when she joined the Women’s League for Peace and Democracy,

a liberal organization that promoted political and social equality.

"But she also kept

her rich friends," McManus says. "She just did not talk about

politics with them."

It was while McManus was

studying at UCLA that she started to become political. It was 1941 and

the United States had declared war on Japan and entered World War II.

She witnessed the roundups and internment of Japanese American students

at UCLA.

"That was my first

radicalizing experience," she says.

While World War II raged,

she decided to go to Spain. Her father had "all these right-wing"

connections that made it possible for her to enter Spain. Once there

she met with people who had been victimized under Franco. After a year

in Spain, McManus returned to the United States and went to work as

a reporter for the Baltimore Sun. It was there that she experienced

what she calls a "deeper radicalization" when she saw how

blacks were mistreated and discriminated against. It was the mid-1940s

and segregation was stringent.

"I was becoming more

and more radical," she says. "I was working at the Baltimore

Sun when the atomic bomb was dropped."

Winston Churchill’s

1946 speech warning that an "iron curtain" would cut through

the middle of Europe changed her life. The Cold War had started and

with it the persecution of left-wingers in the U.S., she says.

| "In

the late 60s, people would do anything for their government, not

anymore. You can’t sustain it. Revolution is a moment." |

At the time McManus was

covering the United Nations for The New Republic, a liberal weekly magazine.

But she soon ended up on a black list and work dried up. "I never

had such a good job again," she says.

From there she went to The

National Guardian, a progressive weekly in New York City. The weekly,

co-founded by John T. McManus, her second husband and a well-known figure

in progressive politics who ran for governor of New York as the American

Labor Party candidate in 1950 and 1954, was one of the few publications

to openly denounce Senator Joseph McCarthy’s hunt for Communists.

Although McManus says she

was never a member of the American Communist Party, she might as well

have been. "Our telephones were tapped," she says. "We

would get strange calls at night. Every time I traveled I was always

harassed when I would come back to the U.S. But I did not mind being

harassed. It’s part of the game."

By the 1960s McManus had

become a full-fledge leftist, involved in both the black power and the

anti-war movements. Her husband had died a few years earlier and she

was looking for a new start. When Cuba’s TriContinental magazine

offered her a job as a translator in 1969 she took it.

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

At the time, Castro’s

government was in desperate need of professionals to replace the middle

class that left for Miami. He invited university professors, doctors,

psychologists, journalists and anyone else willing to take part in the

creation of the new Cuba. For McManus, the decision was an easy one.

The best years of the U.S. left were over. "I loved Cuba already

because I had been here several times," she says. "I knew

people were very enthusiastic and if anybody was going to make it would

be Cuba."

McManus says she began to

loose faith in Castro in the 1970s and no longer believes in the revolution.

She openly criticizes Castro’s policies and describes his government

as a "military dictatorship."

"I was never so blindly

partial," she says. "Most Americans are quite uncritical.

They are a lot more starry-eyed than I am. I could easily see there

was nothing being done to develop the country. As long as the paternalistic

relationship continued with the socialist block there was no need to

produce. And now we are living the consequences of that."

Nowadays McManus supports

herself as a freelance travel writer and translator. And, like other

Cubans, her family in the United States sends dollars. But before she

became disenchanted she eagerly to contributed to the Revolution. She

worked as a translator for TriContinental magazine until the late 70s.

She also became a member and eventually president of the Union of North

American Residents, a group that the U.S. government describes as "a

propaganda apparatus of the Cuban government." The group of about

30 American expatriates, "100 when there was a party," would

show their support for the Cuban revolution by marching waving American

flags in Havana parades every May 1, International Workers Day.

|

"Most

Americans are quite uncritical. They are a lot more starry-eyed

than I am. I could easily see there was nothing being done to

develop the country.

"As

long as the paternalistic relationship continued with the socialist

block there was no need to produce.

"And

now we are living the consequences of that."

|

It was at one of the meeting

of the American Union, as it was known among the members, that McManus

met William Lee Brent, her current husband and a former member of the

Black Panthers Party. In 1968, Lee Brent shot and seriously wounded

three San Francisco police officers in a robbery-related shootout. A

few months after the shooting and while free on bail, Lee Brent hijacked

a TWA airplane bound for New York City from San Francisco to Cuba where

he has been in exile ever since. He is still wanted by the United States

government for robbery, the shooting of the officers and the hijacking.

Lee Brent spent 22 months

in a Cuban jail suspected of being a spy. After his release he worked

on a sugar cane plantation, graduated with an arts degree from the University

of Havana, taught English to high school students and worked as a journalist

at Radio Free Havana, a place where many Americans work.

"The one thing we all

had in common was our respect and unbridled admiration for Fidel Castro,"

wrote Lee Brent in his autobiography, "Long Time Gone," about

the American Union. That respect started fading after Castro no longer

liked the idea of their organization.

"Cuba began its policy

of trying to reestablish diplomatic relations with other countries so

it became very inconvenient to have all these outspoken crazy exiles,

who did not believe in their own governments, organized and visible,"

McManus says. "We became sort of troublemakers so by the late 1970s

the Cuban government disbanded all unions."

Lee Brent, one of 77 American

fugitives living here, sits in the living room and nods in agreement

as his wife speaks. He refused to share his opinions on Castro and the

current situation in Cuba. In a previous interview he said he doesn’t

doubt Castro would turn him in if that would serve him.

"Politics is politics,"

he said in the 1998 interview. "If the big man thinks he can get

some advantage out of peddling me to the Americans, he’ll do it."

| "There's

a lot at stake, not just personal power but the goodies," McManus

says. "The people at the top live a better life." |

Like McManus, Americans

who live in Cuba are a select group of journalists, translators, teachers,

artists, people who have married government officials and those running

from the American government. There are 545 Americans registered with

the U.S. Interest Section. But this number only represents those on

the island for business purposes. How many people are on the island

for purely ideological reason is hard to know.

"The are no more than

100," a Western diplomat said. "They no longer have the ideological

fantasy that this is paradise."

Those on the island for

ideological reasons include people who are running away after they committed

crimes in the United States and found a safe haven in Cuba during the

60s and 70s.

Americans living in Cuba

fall in a legal gray area since under U.S. federal law no American citizen

is allowed to work for a foreign government. In Cuba, anyone who works

is working for the government.

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

Most of the Americans I

encountered were unwilling to talk to me. The main reason they gave

was that they want to maintain ties with the United States and be able

to travel back and forth. Sure the government knows they are there,

they said, but they felt uncomfortable drawing attention to themselves.

A few of them freelance for major news networks and felt their jobs

could be jeopardized.

"You really put them

in danger by writing about them," the diplomat agreed.

McManus was the exception.

The Cuban government does not really care what foreigners think, she

says. Many Cubans share her opinions but they don’t express them

because "it’s too close to the truth and too close to the

top," she says.

It almost seems as if this

is the first time McManus has shared these ideas. She’s anxious

to talk about the lack of democracy, "You have to have a society

that is run by rules and regulations," she says. "But I think

there is a difference between a country that is run by law and order

and a country that is run by hierarchy." She talks about Fidel

Castro’s inconsistencies. "He just inaugurated a statue of

John Lennon," she says incredulous. "He was the one who banned

The Beatles back in the 1960s but now they are OK."

Nonetheless, she’s

content to stay on the island, "I have no desire to go back,"

she says as she pets her longhaired dachshund. I have no house there.

I have good medical care here and a very nice house."

McManus lives in a quiet

and airy apartment in Miramar, a tranquil and swanky residential area

outside of Havana, where children play in parks and where Cubans and

foreign businessmen jog, walk their dogs and take strolls down La Quinta

Avenida, an avenue filled with colonial-era mansions that now serve

as embassies or as headquarters for major corporations doing business

in Cuba.

McManus recognizes that

she lives a privileged life because she has access to dollars. "If

you can live better it is easier to tolerate other things," she

says. "Foreigners don’t have to scramble around to find where

their next meal is coming from, or stand in line eternally or go to

hospitals that are filthy and don’t have medicine."

It’s not that foreigners

have more rights than Cubans, she says. "We get to do things that

Cubans do. It’s just that we have more money to do them with. If

there is not enough in my ration or if I don’t like an item I can

always trade it or give it away but I can always buy things at the dollar

store."

Not only does McManus have

access to dollars, she is also able to travel, a luxury very few Cubans

enjoy. Even if they have the money, Cubans must be invited by someone

abroad to get the government’s approval to leave. McManus goes

to the United States every year, to visit her husband’s relatives

in Californian or to see her family in New York. "This year I am

going back to my grandson’s wedding in Maine," she says.

|

"You

have to have a society that is run by rules and regulations,"

says McManus.

"But

I think there is a difference between a country that is run by

law and order and a country that is run by hierarchy."

|

If McManus dislikes Cuba

now she still remembers being a believer, "Before it was much more

egalitarian," she says. "Everyone lived comfortably without

dollars. But after the Special Period it was obvious Cuba had to open

up to capitalism. Before everything was a barter relationship, oil for

sugar, troops in Angola for everything else we got from the Soviet Union."

McManus says she is just

saying what she and many of her Cuban friends see.

"There's a lot at stake,

not just personal power but the goodies," McManus says as she opened

the door to her terrace to let the warm wind in. "The

people at the top live a better life."

McManus came to Cuba lured

by the revolutionary dream once tangible. Her idealism is long gone

and what keeps her here is her husband. After all, Lee Brent is still

wanted by the United States. Since Cuba has no extradition treaty with

the United States they feel safe living on the island. It also helps

that she lives in relative comfort. I wondered if she would be as critical

had she experienced the stifling violence and poverty of most Latin

American countries. To a certain extent, McManus is like many American

expatriates who go to other countries looking for whatever is missing

in their lives. Like Jimmy Buffet sings, "Some of them go for the

sailing…Brought by the lure of the sea …Tryin' to find what

is ailing…Living in the land of the free."

For most foreigners life

on the island is harder than it would be in their home countries but

they live a lot better than most Cubans. They have access to dollars,

can travel and many are part of the government bureaucracy.

| They

describe Cuba as, "a paradise, a dream come true, and an example

for El Salvador to follow." For them, life here couldn’t

be better. |

Soledad and Felipe, a Salvadorian

couple that moved to Cuba at the start of the Special Period, are the

exception. Home is a massive 1,400-unit apartment building. Three more

Soviet-style buildings just like theirs complete their "neighborhood."

The fact that you have to walk a couple of blocks out to catch a taxi

does not bother them. Nor does the small apartment. Their tiny living

room serves as a dining room too and they keep a desk and book shelves

in a corner for when their 17-year-old daughter comes to visit from

a Havana University campus outside of the city. The deep blue refrigerator

has to be kept in the living room as well since the kitchen is too small.

The wall is taken by huge paintings of Fidel Castro and El Che.

"The small painting

of Charlie Chaplin is kept because Soledad is a fan," says Felipe

referring to a painting set above a couple of old armchairs that were

made functional after their holes were covered with duck tape.

Soledad and Felipe, both

42, have lived in the same building since they arrived in Cuba 11 years

ago. They’ve lived through the harshest of times yet they describe

Cuba as, "a paradise, a dream come true, and an example for El

Salvador to follow." For them, life here couldn’t be better.

While McManus began to tire

of Cuba’s revolution, in the 1970s Soledad was working on duplicate

it in El Salvador. Soledad, her guerilla name, and the name she likes

to be called by, is articulate and affable. A woman with brown skin

and eyes and dark short hair, she is sharp and full of energy. She smiles

as she speaks of the time when she first got involved with the FMLN,

one of the leftist guerrilla groups involved in El Salvador’s violent

civil war during the late 1970s and the1980s. She was just 17 years

old and still in high school.

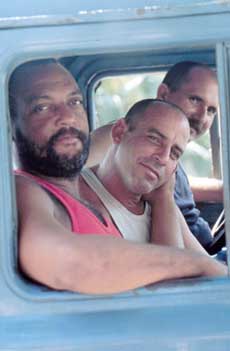

|

|

photo

by Ana Campoy

Soledad and

Felipe in their apartment.

|

For Soledad joining the

guerilla movement when it first started in the 1970s was more than an

ideological pursuit. The deplorable situation they were living and the

daily sense of insecurity prompted the two of them to take action. "We

wanted to change our reality," Soledad says, and then she adds

laughing. "What

we wanted was to build heaven on earth. We did not understand why we

had to wait until after death."

Countless corpses would

be left on the side of the roads to teach people a lesson, Soledad says.

The Salvadorian government waged a psychological of repression. But

Soledad and Felipe continued to participate in the FMLN. Their awareness

and activism developed from the discussions at her church. "We

never spoke about Cuba," Soledad says. "We had heard of Fidel

and of El Che but we were living our own reality. We never thought we

would end up here."

"It was through our

priest that we started to develop a social conscience," Felipe

interrupts.

Felipe "El Gato"

Rodríguez wears a bright red t-shirt with FMLN written in white

letters, but he does not fit the profile of a guerilla fighter. He is

barely 5’2’’ and fragile-he lost a kidney in the late

1980s and the other had to be removed in 1993, the result of not having

access to health care. His skin has the yellowish tint of dialysis patients

and he has to stop every few minutes to take in air. But he’s alive

and it’s thanks to the Cuban revolution. "If Cuba had not

offered to help us he probably would not be here." Soledad says.

The two came to Cuba thanks

to a program to help those who have participated in social movements

throughout the world. They arrived at the beginning of the Special Period

and watched as more than 30,000 people left Cuba the summer of 1994

when Cuba’s economic situation became intolerable. But the scarcity

and the harsh times reinforced Soledad and Felipe’s faith in the

revolution. "Scarcity was nothing new," Soledad says. "We

were used to it in El Salvador. Sure you had things there but if people

don’t have money to buy them it’s as if they were not there."

During the Special Period,

the Cuban economy was basically in freefall. Nevertheless, Felipe received

the medical attention he needed during the eight months he was hospitalized

after his surgery. "What would we have done in El Salvador?"

Soledad asks, knowing first-hand the difference between Castro’s

Communism and El Salvador’s democracy. "We wouldn’t have

been able to pay for his surgery, all the medical attention he needs

and the expensive medicine."

| While

Soledad and Felipe imagine, Almendros and McManus remember that

moment when revolution was palpable. |

Soledad, who works as a

teacher’s aid, talked of how during the special period the unemployed

were guaranteed at least 60 percent of their salary. "In El Salvador

if you loose your job that is your problem," she says.

Sure there were lots of

things missing in Cuba during the Special Period but in El Salvador

there was always a sense of anxiety. "We had some comforts but

we also had debts," Soledad says. "There was always insecurity.

People there can’t go to university. They have to work to help

support their families."

The only criticism toward

the Cuban government the couple has is the paternalism that they say

the Cuban people became accustomed to. "They used to live in a

crystal ball and they want things to be like when the Soviet Union was

around," Soledad says. Cubans nowadays don’t appreciate the

revolutionary values of hard work and solidarity like they used to,

Soledad says. And they don’t appreciate its benefits.

"In Cuba," Soledad

likes to point out, "everyone who wants a university degree can

get one."

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

The best example is their

only daughter who is on a full government scholarship studying to become

a teacher. This too could never have happened in El Salvador, she says.

Soledad and Felipe first

left El Salvador in 1982. The civil war there was in full force. Soledad’s

brother had been shot by paramilitaries and one of their comrades, after

being arrested and tortured, gave their names to the government. Soon

after men dressed in civilian clothes came looking for them.

"I always told my mother

not to open the door if those knocking were not in uniform," Soledad

says.

"The ones in civil

clothes were the death squads," Felipe adds to make sure I understand

the situation they lived in.

The men knocked on their

neighbor’s door. The next day Soledad and Felipe left and went

to live on the border of Nicaragua and Honduras where there was still

a Contra resistance. "We had to help somehow," Soledad says.

"That’s when we realized our struggle was not limited to El

Salvador. We were fighting an international cause."

Both of them enlisted with

the Sandinistas, who, in 1979, had toppled the government of Anastasio

Somoza and by 1982 were waging a war against the American-backed Contras.

The Sandinistas supported the FMLN, and defended that revolution. Felipe

was part of the reserved battalions and he fought in the front a few

times. Soledad was part of the committees for the Sandinista defense,

something like the Committees for the Defense or the Revolution in Cuba.

"We wanted things to settle down so we could go back to El Salvador,"

Soledad says. "When we were about to return Felipe got sick that’s

when we decided to come to Cuba."

The failure of the FMLN

to take power resulted from the divisions within the movement, Soledad

says. The FMLN signed a peace agreement with the Salvadorian government

in 1991 and the following year became a political party.

"We didn’t accomplish

what we fought for," Felipe says. "There is still a lot of

work that needs to be done."

It’s not that the left

in El Salvador is finished, Soledad says. "Now we have to use politics

and not weapons."

They haven’t lost hope

and wish to one day return and help El Salvador become more like Cuba.

"Do you think this

is possible?" I ask.

"In the next few years,

I doubt it," Soledad says while laughing. "But we hope to

go back and at least help in ending government corruption."

I realized that it is their

idealism that keeps them going. They keep in touch with Roque Dalton’s

widow and other Salvadorian exiles who have made of Cuba their home.

It is here that they can still find people who share their ideals and

where they can plan how to influence change in El Salvador. Imagining

a better future for El Salvador will have to do for now. They won’t

go back to their native country any time soon. Doing so would mean Felipe

not getting the life-sustaining medical attention he needs.

While Soledad and Felipe

imagine, Almendros and McManus remember that moment when revolution

was palpable. "Revolution is a moment," McManus told me. But

it was that moment of revolution that gave Almendros the opportunity

to see a whole village go from a place where illiteracy was as rampant

as parasites to a place where children grew up to be engineers, doctors,

teachers. It was also that moment that allowed McManus’ husband

to find a safe haven where a prison cell was replaced by a classroom.

It was that revolutionary moment that gave Felipe a second chance in

life.

That was the moment that

I was trying to understand and to a certain extent relive when I first

went to meet Leoni back in Italy. Compared to now, it seems the 1960s

was a time when it was easier to be an idealist, a time when people

cared about more than just their own material well being. It was a time

when social justice and equality were thought of as possible realities

and not just the fantasies of radicals; a time when heroes where more

than athletes and pop stars. But that moment is long gone. And now Cuba

is a paradox of idealism and authoritarianism. Now, these foreigners

are torn between the idealism of the past and the harsh reality of the

present. And all we, my generation and I, have left are the heroes of

an earlier generation.

Back

to stories page