Son

de Camaguey

By Angel

Gonzalez

"Y morir por la

patria es vivir."

Cuban National Anthem

From my airplane window

I look down at the coast of Cuba, an island known by many names –

the Bulwark of the Indies, the Faithful Isle, the Pearl of the Antilles,

the Lady of the Mexican Gulf.

| How

does Carmelo fit in our long familial tradition of war-mongering,

rebellion and political involvement? That’s what I’ve

come to Cuba to find out. |

'Cuando salí de Cuba…'

says a popular 60's tune. 'When I left Cuba, I left my life, I left

my love… when I left Cuba I left my heart buried in there.' I have

never left Cuba, but I am returning to the country my father fled in

1961, to visit for the first time the cities and landscapes I have imagined

since childhood. I’ve considered these cities kidnapped, frozen

in a Spartan, alien lifestyle, while the rest of us, the Cuba that left,

prospered.

The island below is the

land my ancestors discovered, populated and built. Looking at the beautiful

landscape bathing in the Caribbean I struggle to hold back my tears.

It must have been difficult to leave. Maybe that's why my uncle, Carmelo

Gonzalez del Castillo, chose to stay, even though most of his family

went to exile.

Who was Carmelo Gonzalez?

From what I know, he was an idealistic young man deeply involved in

one of the most important events in the history of the Western hemisphere:

the Cuban Revolution.

Carmelo was a revolutionary,

a counter-revolutionary, and the once again part of the Revolution.

Some say he despised Castro, but some say that after serving time in

Castro’s prisons, he lived out his life as a committed Communist.

How does Carmelo fit in our long familial tradition of war-mongering,

rebellion and political involvement? That’s what I’ve come

to Cuba to find out.

|

|

photo

courtesy of Angel Gonzalez

Carmelo and

his wife, Josefina

|

"Hay sol bueno, mar

de espuma…" 'There's good sun and a sea of foam', reads an

advertisement at the airport, promising perfect beaches to the hordes

of tourists who come looking for sex, music and sun. To me, those words

say much more: they are from a poem written in 1889 by Jose Marti when

he lived in exile in Newport Beach, a poem that, line-by-line, my grandmother

asked me to memorize when I was a small child.

I too lived in a kind of

exile, born in Venezuela, but brought up in the Cuba of my grandmother's

memory. From her I learned Marti's poem, the name of Cuba's first seven

cities, the order in which they were founded, and the sweet Caribbean

accent of the Cuban province of Camaguey.

My grandmother Elba del

Castillo is an aristocratic woman, a descendant of Mambises, the liberal

Cuban planters who rose against Spain in the wars of 1868 and 1895.

She was born in the early years of the Republic. Her father, Ángel

Castillo y Quesada, a Cuban Cavalry commander in the war of 1895, followed

the military tradition of his father, General Ángel del Castillo

Agramonte, one of the original conspirators behind the birth of the

First Cuban Republic in 1868. My grandfather was killed, according to

the Cuban history books I used to read as a child, by a Spanish bullet,

crying out "see how a Cuban general dies!"

Their battles became my

childhood fantasies, and in my grandmother's room, full of books of

Martí and maps of Cuba, I forgot entirely about Caracas and the

limited life of a five-year-old. The endless stories about pirates,

elegant ballrooms, revolutions and the strange Marquis of Santa Lucía

- a distant relative of my grandmother who had lived in England and

ate canaries and mockingbirds - were far more interesting, far more

real.

My little brother and I

commuted between kindergarten lessons about Bolivar's liberation of

South America, and my grandmother's Cuba. In both worlds, we indulged

in the cult of Independence heroes, but in my grandmother's country

we had heroes that bore our name.

In the same shelf where

my grandmother placed a glass of water to our ancestors - a magical

custom inherited from her black nanny - there was an album that contained

a picture of her family: my grandmother, my grandfather, Carmelo González

de Ara, a dark, elegant Spanish accountant and Rose-Crucian, and their

two sons, Ángel and Carmelo. Ángel, my father, a student

at the University of Havana when the photograph was taken, had inherited

his mother's fair skin and ironic smile. Carmelo, my uncle, was a revolutionary

student leader still in high school at the Liceo de Segunda Enseñanza

of Camaguey. He bore his father's dark skin and fiery, Arab eyes.

| My grandfather

was killed, according to the Cuban history books I used to read

as a child, by a Spanish bullet, crying out "see how a Cuban

general dies!" |

The picture was taken in

1960, barely a year after the fall of Batista and the triumph of the

Cuban Revolution. In the following months, that family¸ like many

others of the time, would be divided by the Revolution.

Many members of the middle

class had supported the ousting of Batista, but couldn’t stomach

the executions* and opposed Fidel Castro's embrace of Communism. "Even

the music is sad," my grandfather used to say of the socialist

hymns of the era. In 1961, he arranged for my father and Carmelo to

take a ship to Venezuela. My father left, but his brother stayed. By

this time, Carmelo had turned from revolutionary to counterrevolutionary

and he was determined to oust Fidel

"Carmelo," my

grandmother still says when calling my brother Miguel, mistaking him

for her son. "Your father was very smart, but Carmelo was always

surrounded by women. And he was a 'guapo', " a Spanish word that

means 'handsome' but in Cuba, also reckless and brave. A 'guapo' like

our grandfathers, the legendary fighters for the Cuban independence,

had been.

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

A view of

Havana.

|

It’s an early, fresh

Cuban morning, and I wake to the sound of Fidel’s voice on TV.

I am staying at a splendid 1950s apartment in El Vedado. Sunlight fills

the room, the smell of the sea, mixed with gasoline, is everywhere,

just like the chirping of canaries. The caged is a Cuban obsession –

my father has had dozens of the little birds.

This is the center of Havana,

where the great hotels are. The Nacional, the Capri, the Habana Libre.

Amid the ruined high rises and faded condo buildings, crowds wait for

the ‘camellos,’ the huge Hungarian-made buses that transport

up to 400 people, to take them to work. I try to picture Carmelo as

an eight year old in 1950, taking a different, American-made bus to

school.

"Habana, quien no la

ve no la ama," who hasn’t seen it, cannot love it, goes the

saying. And it is true: even though I was brought up with stories about

its splendor, I never imagined it like this, the most beautiful city

I've ever seen. Its late 19th cenutry architecture reminds me of the

monumental constructions of Madrid and Barcelona. Its warm climate and

veranded houses remind me of Sevilla. A huge Cuban flag flies from the

Hotel Nacional, its lone star waving in defiance. In the presence of

this flag I feel something resembling pride, nationalism. It’s

the symbol my grandfathers fought for.

I try to picture how it

must have been back then, in the times of ‘Cuba Libre.’ Some

things must look the same: the Art Deco buildings, the incredible abundance

of 1950s cars. But many things that my father talked about are missing:

the street vendors who used to sell mussels in lemon juice, the advertisements,

the elegantly clad people, the bourgeoisie that built these modern houses

and apartments, now crumbling structures.

New things are there, though:

the Yara movie theater that shows films by Tomas Gutierrez Alea, and

Coppelia, the nationalized ice-cream parlor where Cubans stand in line

to feed the national obsession for 'helado', or icecream. My father

wouldn't recognize the Soviet-made Ladas and the Eastern German Trabbis,

symbols of the alliance with the socialist countries; and he would be

surprised at the Toyotas and the Nissans driven by the European, Canadian

and Mexican managers of the new economic regime.

I feel vaguely at home,

for the weather, the colors, and the sounds of the street are remarkably

like those of Caracas. These high rises are part of a city that used

to be American: they wouldn’t be out of place in Miami's South

Beach. The streets are lined with trees, and their shadow, combined

with the ocean breeze, ease the tropical warmth. But

what fascinates me is that Havana is frozen in the 1950s. Cuba was very

developed back then, while Caracas, the capital of a far bigger and

richer nation, was barely emerging. Life in Cuba now happens inside

structures that bear the façade of another era, like insects

dwelling on a hollow, fallen tree.

| Hundreds

of foreigners walk the streets amid thousands of Cubans. Everyone

is a hustler: I can barely walk a couple of blocks before an Habanero

coming at your side to peddle cigars, a tour of the city, or a fine

woman. |

But it’s also dynamic

here. There is energy. Hundreds of foreigners walk the streets amid

thousands of Cubans. Everyone is a hustler: I can barely walk a couple

of blocks before an Habanero coming at your side to peddle cigars, a

tour of the city, or a fine woman. Bicycle taxis swarm around tourist

hotspots. The bar at the rooftop of Hotel Inglaterra is as alive with

music as it was during its heyday in the 1930s. Life is returning to

the frivolous city the Revolution set out to change.

From the steps

of the imposing University of Havana, founded in 1737, I can see the

ocean, and I imagine my father and Carmelo meeting there, by the Malecon.

My father, the practical 22-year old engineering student on his way

to Venezuela, trying to talk his little brother into abandoning the

fight against Castro, a fight that was not Cuban anymore. It was in

the hands of the United States and the Soviet Union, the Cold War superpowers.

Carmelo refused. And so my father left his brother standing there, by

the Malecon, an angry youth stranded on this tragic island. That was

the last time they saw each other.

Carmelo Hector Antonio Gonzalez

del Castillo was born in the city of Puerto Principe de Camaguey in

1942, at a time when the world was at war and Hemingway was chasing

Nazi submarines off the coasts of Cuba. He belonged to an increasingly

Americanized middle class that profited from the prosperity brought

by the war.

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

When I fly to Camaguey,

I see first the red tiles of his city, so different from the Bourbonic

glitz of Havana and so reminiscent of the early days of colonization.

I can picture our great-grandparents riding on horseback through the

surrounding plains, their sugar cane factories set on fire by the Spanish

loyalists.

'What a joy. The city of

Ignacio Agramonte, Angel Castillo… this is the birthplace of immortal

feats, and the immense dust of the streets seemed luminous to me. "

These lines were written in the late 1880s by Enrique Loynaz del Castillo,

a distant relative of mine and Carmelo’s cousin, who eventually

became one of the main figures of the war of 1898. Loynaz was born in

exile, and the Camaguey he returned to was the Cuban city that kept

the traditions inherited from the Conquest in their purest form, and

many families, like the Castillos, kept a strict record of their genealogy,

tracing it back to the Conquistador Vasco Porcallo de Figueroa.

That’s the immemorial

Camaguey of my implanted memory – snapshots from my grandmother’s

stories and Caracas and Miami’s nostalgic exile newsletters. But

as I descend from the Soviet-made Antonov whose safety signs are still

imprinted in Cyrillic letters, I wonder if 40 years of Communism will

have erasedall traces

of my family’s past.

It's dusk already, and churches

and royal palms dominate the skyline. It's hot, and humid, and there

are very few electric lights on - it looks sinister and impoverished,

this city of my ancestors. But in the central plaza, as if to assuage

my fears, there’s a statue of a man closely related to Carmelo

and to our family: Ignacio Agramonte, Camaguey’s most prominent

warrior in the struggle for Independence against Spain.

Yolanda del Castillo is

my grandmother Elba’s sister, the youngest of the 13 children of

Colonel Angel Castillo Quesada. She is 86 years old, and I am meeting

her for the first time. I talked to her couple of times by telephone,

and when I call her from the Gran Hotel in Camaguey, she recognizes

my voice.

"Family is a strong

tie," she says, adding that I talk just like my father, who lost

his Cuban accent a long time ago and now speaks like a Caraqueño.

Yolanda lives on Jaime street,

right behind the Iglesia de la Soledad, Camaguey's impressive Romanesque

church. In the entrance a young woman awaits. She has very pale skin,

and she looks exactly like my grandmother, but sixty years younger.

"Hola. I am Livia. We are family," says Livia del Castillo,

Yolanda's niece, embracing me cautiously.

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

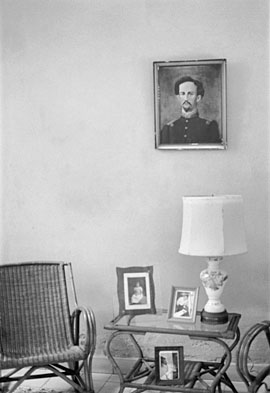

When we enter my great-aunt’s

house, a lone oil painting of my great-great-grandfather dominates the

wall - General Ángel del Castillo Agramonte, his mustache fashioned

to a point, his beard clipped, and his military uniform adorned with

the stars of his rank. That portrait was painted in 1868, and it is

present in every house of every branch of our family, be it in Miami

or in Caracas. We were taught to venerate it, and I always carry a copy

with me. But I never imagined the original to be in color - all the

copies my family has, which come from a photograph taken in in a hurry

before leaving in 1960, are in black and white. "That is the portrait

of Abuelito," says Livia. I had never heard anyone refer to our

glorious ancestor with such intimacy.

"Abuelito" had

captured the first canon used by the Cuban Liberation Army during the

First Independence War, which the revolutionary government baptized

as "The Angel" in his honor.

"Angel del Castillo

had created the best trained and most brilliant nucleus of the Liberation

Army at the time," says Jorge Juárez Cano in his book "Apuntes

de Camagüey." His exploits ended in 1869, when he was killed

trying to defeat a Spanish garrison. He is described by historians as

an impulsive, violent man with endless courage. ‘La tempestad a

caballo’, the storm riding on horseback, as he was called by his

followers. Carmelo and my father grew up in the shadow of this portrait,

surrounded by war memorabilia and the past glory of a patriotic family.

"When Carmelo was a child, he wanted to be as brave as Abuelito,"

says Yolanda.

Yolanda reminds me of my

grandmother-- aristocratic, headstrong, orderly. She and her husband

were like parents to Carmelo and my father when they were children.

At times, they spent as much as six months a year living at their home

and at their hacienda. "We never had any children, so they were

like ours," she says. The Carmelo of Yolanda's stories is a brave,

impulsive and intelligent little kid.

"He was courageous,"

says Yolanda. "We gave a horse to your father and Carmelo when

they were little. We kept it in our ranch. One morning, upon hearing

that the animal had fallen inside a hole in the field, Carmelo woke

up and ran outside, screaming 'I am going to save my horse.'" He

was only five, but willing to save the horse upon which he would become

a tempest, like his great-grandfather. The horse could be saved, but

was eventually sold. With the money, Yolanda bought Angelito and Carmelo

their first suits, preparing them for a bourgeois, capitalist Cuba that

was entering the fifties under the wing of the United States.

I walk by the "Casablanca"

movie theatre, a whitewashed remainder of the times when the Cubans,

the most avid moviegoers of the Western Hemisphere, came to watch Humphrey

Bogart and Ingrid Bergman. In 1959, revolutionaries, my uncle among

them, put a bomb in this place.

Carmelo had grown up to

be a popular student in his high school, always surrounded by friends.

At 17 he was elected as the president of the school's student federation.

It was Carmelo who identified the most with the family's Independence

heroes - and for a young man interested in politics at the end of the

1950s, the budding revolution against the corrupt dictatorship of Batista

offered an irresistible draw. He prepared Molotovs, distributed political

fliers, and sold revolutionary bonds that Yolanda bought in quantity.

The Revolution triumphed

in January 1959. Fidel entered the city and my grandmother, like many

other middle class housewives, offered shelter to the long-haired olive-clad

barbudos on their march to Havana. The students expressed their sympathy

towards the new government by wearing red and black armband with the

colors of the M-26 movement. Many thought democracy would follow.

But the Revolution proved

to be 'olive green on the outside, red on the inside,' as many Cubans

say. When Castro embraced Marx, Carmelo, like many others who had cheered

the revolution, objected.

Huber Matos, the revolutionary

commander of the province of Camagüey, wrote a letter to Castro

in October 1959 resigning from his post and warning him of Communist

infiltration. Castro answered by sending the legendary commander Camilo

Cienfuegos to Camaguey to arrest Matos who was then charged with plotting

an uprising and sentenced to 20 years in prison.

Others were unhappy as well.

When Soviet foreign minister Anastas Mikoyan visited Cuba, in April

1960, he placed a wreath in the shape of a hammer and sickle on the

grave of José Martí. A group of students led by Alberto

Muller protested by placing a wreath in the shape of a Cuban flag on

the following day.

The students carried banners

that read 'Long live Fidel' and 'Down with Communism'. The police broke

the march and threw many of the students, including Muller, who knew

my uncle, in jail. "It was there when we realized that Castro had

the intention of establishing a totalitarian regime," says Muller,

who now lives in exile in Miami.

|

It

was Carmelo who identified the most with the family's Independence

heroes - and for a young man interested in politics at the end

of the 1950s, the budding revolution against the corrupt dictatorship

of Batista offered an irresistible draw.

He

prepared Molotovs, distributed political fliers, and sold revolutionary

bonds that Yolanda bought in quantity.

|

In the next couple of months,

my uncle and others created the Directorio Revolucionario Estudiantil

to overthrow Fidel. Muller said that at the root of this group were

the student organizations that led the fight against Batista. Carmelo,

then the president of the Federation of Students at his high school,

was among those ready to form the counter-revolutionary Directorio.

"We are going to do to Castro the same thing we did to Batista,"

he told a cousin back then, and it wasn’t long before he came the

Directorio’s provincial leader in Camaguey. "Cuba has a very

violent history," says my great-uncle Laines as we enter his beautiful,

run-down house in Tomás Betancourt street. "We have always

been under attack. Even our ancestors came here attacking." He

hugs me frequently, not quite believing the fact that I am there. Lagnes

was a baseball player, an adventurer. "I was the black sheep. There

is always one in every generation, " he says, referring to his

favorite nephew. I know I am following the steps of Carmelo, for he

lived in this house for a while.

He points to his brown and

white square shirt. "This was a gift from your uncle," says

the tall 90-year old. "What a great man he was. What strength,

what character," he says.

And the time he lived in

called for it. After the arrest of Huber Matos, the acts of violence

multiplied, and most Cubans unable to live with a regime that had turned

Communist, left. When the revolutionary governor of Camaguey heard that

my father and his family were leaving, he summoned my father to his

office, asking him to convince Carmelo to leave as well. Carmelo refused.

During that year of 1961,

a strong guerrilla force composed of anti-Communist students and peasants

operated in the mountains of Escambray. Bombs exploded in the cities.

Electricity plants were sabotaged. Insurgent expeditions disembarked

every month and the government detained more than 100,000 people to

prevent an uprising on the eve of the Bay of Pigs. Sometimes it seemed

as if the Revolution would fail – but its opponents, who counted

on American aid to counter the Soviet support to the regime, were crushed.

In a dark room, full of

portraits of old baseball legends and newspaper clippings, Laines keeps

an archive of our family's history. "Look at this," he said,

handing me a huge packet of newspaper clippings, containing the history

of the Castillos. "Our genealogical tree," he said. It’s

a stack of yellow paper full of names of Spanish army officers, slave-owning

planters, arbitrary oligarchs, Cuban independence fighters and liberal

revolutionaries. They were men of wealth, men of violence. Among the

papers I find a yellow typewritten sheet, dated from June 1962. Carmelo

Hector Antonio González y del Castillo, it states, was part of

"a group of counterrevolutionaries that had been operating in our

country under the political direction of the State Department of the

United States, and its organization of betrayal and espionnage denominated

CIA."

According to the transcript,

Carmelo and others were caught unloading a weapons shipment in Santa

Cruz, in the northern province of Pinar del Rio. They intended to set

out for South Florida to join 'mercenary forces' there. They were carrying

weapons, and fired them against security forces when they were discovered.

'Carmelo González y del Castillo was captured with an olive green

uniform and a pistol caliber .975,' says the report.

Yolanda and her husband

were the first to hear about the ambush, on the Voice of America. The

first radio report announced that Carmelo Gonzalez had been killed.

"That very same afternoon I had had an intuition", she says.

"I told my husband to prepare luggage, for we would have to make

a trip. When we heard the news, I knew that was it." Her husband

and my grandfather took Yolanda's car and went out to ask about Carmelo's

whereabouts. They finally found out with State Security that he had

been captured alive. Three months later, he was transferred to Camaguey,

unrecognizable behind his prisoner's beard.

According to Yolanda, young

Communists drove their cars around the prison screaming 'paredón

para Carmelo'. But Carmelo wasn't shot. At 20, he was sentenced to 30

years in prison. That was the end of his counter-revolution.

A bicycle taxi takes me

to the Children Hospital. "This used to be known as La Colonia

Española, a clinic for rich people," says my taxi driver,

pedalling furiously. I step down of the cab, pay my fare, and start

taking pictures of the yellow, formerly luxurious 1920’s building.

A middle-aged man in a guayabera – the Cuban white, plaid shirt

that is still a symbol of tropical elegance – comes towards me.

He’s a state security agent, I’m sure – a journalist

friend who lived in Cuba told me once that the guayabera is the uniform

of state security. He asks me what am I doing, and why I am taking pictures.

"My grandfather died here," I answer.

| Sons

do not belong to their parents — but to their time. |

In April 1964 - Carmelo

was allowed a short visit to my grandfather’s deathbed. He arrived

to La Colonia escorted by a large number of state security guards. "Your

grandfather could barely recognize Carmelo, " says Laines, who

witnessed the encounter.

Carmelo was eventually transferred

to the infamous prison at Isla de Pinos, now rebaptized Isle of Youth.

My grandmother had to traverse the whole island to see him. His rebelliousness

earned him long periods of time in the "gaveta", literally

a "drawer", a small cell with no light, which damaged his

eyesight.

While in prison, he married

his girlfriend Miriam, the daughter of a prominent official of the regime.

Soon after, his sentence was commuted to seven years.

"Carmelo lived here

right after his liberation, " says Laines, showing me Carmelo's

shoes and college textbooks. "He slept in that very same sofa you're

sitting in." When Carmelo was set free in 1969, he found work as

an electrician at a local factory, and eventually divorced Miriam. The

next year he was admitted to the University of Havana, and became an

agronomist.

And in 1974, the same year

that he remarried, this time to Josefina de Quesada, a cousin of his,

and a Communist party militant, he started to work at the Triángulo

3, Camaguey's biggest ranch, of which he would one day become the director.

"Even after he left, he used to come here all the time in his jeep.

-Uncle! Uncle!- he used to yell, and drove me in all throughout the

city." He was 'una panetela', a candy bar.

There's a heavy atmosphere

in Camaguey. The land-locked city is extremely hot, the streets are

narrow, and everybody seems to be working, producing, doing something,

moving around in bycicles or horse-drawn carts. I am lost, buried in

newspaper clippings relating the story of Angel Castillo, watching the

statue of Ignacio Agramonte watch me, and walking the same streets Carmelo

walked once and again. My father made his life in Caracas, a big, cosmopolitan

city, where air conditioned cars clog the highways, and life goes from

offices to shopping malls to highrise appartment buildings to Miami

or New York.

Carmelo stayed in this colonial

city, whose laberynthine cobblestoned streets and one-story quintas

can send you back 200 years. Through these streets he drove his jeep,

in calle Maceo he shopped, in the surrounding countryside he worked,

in this city he died.

"Your uncle was a great

man," says Jesús Rodríguez, one of Carmelo's best

friends and the director of Triangulo 3. Camagüey differs from

the other provinces of Cuba in the fact that its wealth is based in

cattle and not on sugar cane.

The ranch's administrative

headquarters are located in the outskirts of the city. The office is

a small room with green walls, two metal desks and a large window, flies

buzz in. It's hot, and a small cohort of functionaries is waiting at

the door to meet Carmelo's nephew. Everybody seems to remember him,

and they tell me how much they loved him. Such a reaction for a man

who died more than 17 years ago surprises me.

|

|

photo

courtesy of Angel Gonzalez

Carmelo speaking

to an audience of farmworkers.

|

Rodríguez reminds

me of a Venezuelan hacendado, with his macho manners, straw hat and

an assurance that comes from years of experience. The only difference

is that he works for the State. He is a man in his late fifties, the

same age my uncle would be if he were alive.

"He saved me more than

once from being fired," Jesus remembers. I imagine Carmelo as his

friend describes him, sitting in his desk, going through two packs of

cigarettes a day, smoking the butts when he ran out. "He didn't

want to interrupt his work to look for more cigarettes," Rodriguez

says.

That discipline enabled

Carmelo to become a leader in the Triangle. I have a picture of him

clad in a white guayabera, giving a solemn speech in front of an audience,

maybe talking about the wonders of the plan, defending the achievements

of the Revolution.

I ask Rodriguez about Carmelo’s

revolutionary involvement. In Miami, the font of all Cuban gossip, I

had heard that Carmelo might have been a double agent—a circumstance

that would explain the commuted sentence, the decision to stay. Rodriguez

doubts it.

"Carmelo failed when

he was young," Rodriguez explains. "He was a Revolutionary,

but became involved with some people in this Province that betrayed

the ideals they had been fighting for, and he paid for it. But this

is a great Revolution, and it knows how to recognize a leader."

Josefina de Quesada is a

handsome woman in her fifties. A distant cousin of ours, she is the

daughter of Angel Carlos Quesada Castillo, my grandmother's favorite

cousin. Even though she works as chief nurse in one of Camaguey’s

hospitals and she teaches at the local university, she lives in a cramped

apartment in a modest neighborhood close to the train station.

She was a nursing student

when she started dating Carmelo. She became his second wife. According

to Josefina, he was a very picaresque man, always surrounded by beautiful

women.

Josefina, who is accompanied

by her sister Elita, brings out a folder of pictures. And there he is,

larger than life. In one taken in Angola in 1978, he is standing in

front of a truck, shirtless, smiling, looking at the horizon while one

of his comrades aims a Kalashnikov at some unknown target. "He

was an agricultural advisor," says Josefina, who remains a Communist

Party militant.

When I ask again, specifically

what he was doing there, Josefina insists he was a private man, but

only an agricultural advisor. The picture suggests more, but I don’t

bother to press. Instead, I can’t help but feel proud to see my

uncle there, looking at the horizon, carrying the family's martial tradition

to other lands, other continents. I can picture him in the swamps of

Kuanza, giving instructions to Angolese farmers, or who knows, soldiers.

"In Angola they used to mistake Carmelo for a Moor," says

Josefina who was there for a two year stint that overlaped for only

one of the two years of Carmelo's mission, in 78-80.

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

Cuba’s involvement

in Angola reached its paramount in 1975, when the Portuguese colonial

government retreated from the country. Cuban volunteers helped the Movement

for the Liberation of Angola, a Marxist guerrilla, gain control of the

situation. And during the next decade, more than 50,000 Cuban troops

went there, helping the newly established government control insurgency

and repel a South African military invasion. The fight became, in Cuba's

eyes, a war against Apartheid. And Cuba’s victory over South African

troops is regarded as one of the most important feats in Cuban military

history, celebrated both in Cuba and in Miami. Its victor, General Arnaldo

Ochoa, was regarded by many, both on the Isle and off, as a potential

successor for Castro. But he fell in disgrace in 1989, and was judged,

demoted and shot under drug trafficking charges by the same Revolution

that he defended.

Josefina dispels the notion

that Carmelo was a counterrevolutionary. "He failed when he was

very young," says Josefina, making his counterrevolutionary period

seem like an act of immaturity. "He got involved with some people

he shouldn't have been, with that traitor Huber Matos. But when he was

in prison they saw that he was a good man, brave and stubborn, and they

gave him the opportunity to join the Revolution."

"Carmelo could have

left but he didn't, " she says, "because he convinced himself

of the mistake he made when he was young." Josefina said that Carmelo

never became a Communist militant himself, but his honesty and character

were such that he was allowed to join the ranks of the Revolution abroad,

and was given a top responsibility at the Triangle. "He always

had a car," she adds, a sign of his privileged status.

"But the guilt of having

failed at such a young age haunted him for the rest of his life,"

she says. Carmelo, in her words, was repentant of his counterrevolutionary

involvement. And certainly, his life demonstrated it. He worked hard

in keeping up production at Triangle 3, collaborated with State Security,

and participated in the Revolution’s exotic adventures abroad.

Carmelo's heavy smoking

developed into cancer in 1984. The disease was detected in September,

and three months later he died. More than 300 people attended his funeral.

According to several accounts, it resembled an official funeral. The

entourage included representatives from the Ministry of the Interior

who said that Carmelo had worked for State Security, and that his efforts

had been greatly appreciated by the Revolution.

| I can’t

believe that the ghost of my uncle still raises suspicions among

these people. Didn’t he become a faithful revolutionary? Maybe

they don't know the truth either. |

I join a funeral in the

cemetery of Camaguey, built in 1813 by Don Diego Antonio del Castillo

Betancourt, an ancestor of ours and the man who published the first

anti-Spanish proclaim in Cuba. Oddly enough, there's no place better

than this to realize that a mass exodus took place. Many of the graves

are in disrepair, for the family members that should take care of them

are either dead or in exile. The Zayas-Bazan, the Mirandas, the Varonas

- the great names of yore - seem stranded here. The lid of one tomb

has been broken. Morbid curiosity makes me peer inside. I see nothing.

The people in the funeral

march are crying for a dead soldier. Men in military uniform surround

us. I walk with Josefina and Elita, to pay a last homage to Carmelo’s

grave.

Suddenly, one of the graveyard

keepers, a man I had befriended on a previous visit to the place, comes

up to me and warns us to leave the place as soon as we can – a

state security patrol is watching us. "I just received a phone

call from the local Vigilance Committee," he says, visibly nervous.

"They told me that there’s a Venezuelan youth looking for

information about Carmelo Gonzalez del Castillo, who was in prison with

Huber Matos back in the sixties," he says.

I can’t believe that

the ghost of my uncle still raises suspicions among these people. Didn’t

he become a faithful revolutionary? Maybe they don’t know the truth

either. Josefina senses my anger and tries to calm me. She takes me

away, tells me to be brave like a Castillo, and leads me to Carmelo’s

final resting place. "Sons do not belong to their parents, but

belong to their time," Josefina reminds me as we approach the grave.

The remains of Carmelo lay

in a state ossary, in a niche among hundreds. The small white tombstone

sits next to Josefina's father's, and fresh flowers adorn it. I touch

the tombstone and recite a small prayer. It is with mixed feelings that

I come from abroad to pay homage to this grave. I do not agree with

the Revolution my uncle made - especially when several men dressed almost

in rags, wander among the graves, looking at us from time to time. I

suspect they belong to state security, and Josefina's wariness confirms

it. I am sure she told them to come here. The 40-degree heat is making

me dizzy, I am scared, and I want to leave Camaguey forever. Finally,

Josefina, Elita and I join the young soldier's funeral entourage, and

we leave in peace.

Back in Havana I sit in

a terrace overlooking the Paseo del Prado, the city's equivalent of

Champs Elysees. From here I see the Capitol, a perfect imitation of

the one in Washington D.C. I also see the Teatro del Tacon, the Madrilene

buildings, the art-deco skyscrapers built by American banks, silent

monuments to a Cuba that might have been. I wish that Carmelo was here,

sharing a drink with me and telling me if it was worth it, if the country

he inherited is better off now than it was in 1959.

I would ask him if there

are not better ways to establish justice and to satisfy nationalist

pride than give away most freedoms and submit, even symbollically, to

the voice of a caudillo. I wonder if my uncle imagined that the voice

would last for so long. What would he think of his nephew, a student

in an American university, sitting in this terrace full of European

tourists, watching his Revolution come to an end?

In any case, what matters

is that Carmelo, when he was a kid, wanted to become like his great-grandfather.

In this, he succeeded: that photograph of him in Angola will hang next

to the portrait of Abuelito, for generations to come.

Back

to stories page