Spain and Cuba; A 500-year-old

Affair

By Megan

Lardner

|

|

photo

from Yahoo maps

The

"faithful island." authors visited Pinar del Rio, Varadero,

Trinidad, Havana as well as several other towns and cities to

research their stories.

|

"The old Spanish empire

is no longer capable of dominating the lands of young America."

- José Marti, 1890

Ivan, a Cuban philosophy

student, still remembers the scene vividly: It was January 2001 and

the Spaniards had descended on central Havana, draped in robes like

royalty from the 1500s. In the lead, three men in a horse-drawn carriage

rolled leisurely along the tree-lined Paseo del Prado to the clattering

rhythm of hooves. Behind

them, a troop of Spaniards fanned out along the street, throwing candy

to Cuban children. With the kids in fast pursuit, the entourage glided

past crumbling colonial homes and emerged in front of the Spanish Cultural

Center's newly refurbished seafront mansion. There the crowd thickened

and the candy supply ran low. People began to push and grab excitedly,

trampling some children in the midst of the confusion. One of the costumed

Spaniards was especially rude. When

the gifts ran out, he told the kids to get lost. Meanwhile, Cuban television

crews captured the images.

The Spaniards - modern day

diplomats and executives dressed up as the biblical Wise Men for a traditional

Spanish Epiphany parade - barely made it back to their offices before

the eruption. Local press called the Spaniards "undignified clowns"

and "imported monarchs" whose dangerous show encouraged Cuban

children to fight over material objects. In response to the affront,

Cuban officials held a conference called "Neither Kings, Nor Wise

Men" and Fidel Castro warned: "We don't want to add fuel to

the fire in our relations with Spain, but let no one doubt that any

rudeness, provocation, or insult will receive an appropriate response."

His threat is no joke. The original Epiphany parade was banned 40 years

ago after Castro's revolution reinvented Cuba and emphasized national

pride over historical ties. By resurfacing now, the Spanish-sponsored

religious celebration has sparked resentment. Spain, for its part, pleads

innocence. "Our presence is not some kind of re-colonization of

Cuba," says José María Coso, director of the Spanish

Cultural Center in Havana and the parade organizer. He lifts a Cuban

cigar lovingly to his lips and gently exhales smoke. "We're just

trying to preserve our place here."

If most divorced couples

married for 20 years complain about emotional baggage, imagine the unresolved

issues shared by two countries with a 500-year old relationship. During

many of those years, they fought. Then in 1898 after a long, bloody

war, Spain finally picked up its belongings and sailed home. But it

left behind 50,000 soldiers who changed the face of the island; today

their descendants populate Havana's boardwalk among the silhouetted

fishermen and young couples stealing kisses at sunset. If the Cuban

government has gone through several changes of heart toward Spain since

1898, developments in the past ten years also demonstrate the nations'

enduring connections; how a former colonizer has become a necessary

ally; how in the era of globalization, blood proves thicker than water

and makes for some odd couples. Yet the emotional baggage remains.

| Losing

Cuba was a psychological disaster for Spain, like losing a limb. |

Unlike young love, the two

nations are embroiled in a complicated affair. The Spanish lost the

island a century ago, but are now returning to Cuba as business executives

and benefactors. They began arriving in 1991, when Cuba hit an economic

wall after the fall of the Soviet Union. Spain's socialist government,

led by Felipe Gonzalez, rushed to the rescue with millions of dollars

in aid. Gonzalez also encouraged Spaniards to invest. One of the early

arrivals was Carlos Pereda, who opened Cuba's first tourist hotel in

what used to be the sleepy coastal village of Varadero. The town –

a two-hour ride from Havana along sleek highways – has thrived

on the bitter-sweet fruits of tourism. Today pricey Spanish and international

hotels hug the coastline, shaded by thousands of perfectly cloned palm

trees. From a windowless office just steps away from warm Caribbean

waters, Pereda is working after hours on a steamy Saturday evening.

His telephone rings constantly, and the grandfatherly Spaniard jokes

amiably with the callers. Fluorescent ceiling lights glint off a dozen

wall plaques that mark a decade of success. "It was like night

and day when I came to Cuba," he says in an accent still thick

with the lisping zeta of Spain. "Imagine arriving in a country

where 75 percent of your work force is university educated, and the

other 25 percent is highly educated. Here when it comes time to pitch

in to help with a government project, everyone contributes."

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova.

A view of

Havana.

|

Pereda isn't the only one

impressed by the Cuban work force. The tide of incoming Spanish investors

has flowed so swiftly in recent years that they founded the Association

of Spanish Business Executives in Havana. Its president, Rafael García

Arnal, is a friendly Barcelonan with a taste for Habanos cigars. His

optimism is clear as he runs through the statistics; membership is up,

with some 100 Spaniards representing everything from banks to food services

to hotels; there are nearly 200 Spanish businesses on the island compared

to just 36 in 1994; and Spanish firms make up 25 percent of total foreign

investment and 40 percent of all European Union trade with the island.

"We're not just thinking about the distant future – we're

making money now," García Arnal says, his affable face red

from too much Caribbean sun. Like him, other Spaniards are beginning

to call the lush island home. But the club president still looks forward

to his yearly vacations in Spain. "I go there to refresh myself,"

he jokes, alluding to Cuba's harsh political and economic landscape.

Even with the challenges,

Spaniards are reveling in their new connection with Cuba and it seems

that all they touch turns to gold. In 1995, the Cuban government relaxed

strict guidelines and allowed foreigners to own more than a 50 percent

share in a joint business venture. Spanish money poured in. By 1996,

Spanish hotel chains had invested $75 million in the island's tourism

sector alone. But no matter how smoothly business deals unfold, Spanish

executives have learned caution at the bargaining table. "Cubans

complain of Spanish arrogance, something other countries don't have

to worry about because they don't have the same historical baggage,"

says Mark Entwistle, Canada's ex-ambassador to Cuba and now a business

consultant. And arrogance is just one stereotype the old colonizer must

transcend in its evolving relationship with Cubans. Spanish hotel companies

have also come under fire for discriminatory hiring practices. In 1995,

the Spanish-owned Habana Libre hotel in downtown Havana was accused

of trying to "whiten" its staff. "They were firing blacks

to appeal to mostly light-skinned foreign tourists," says Alejandro

de la Fuente, a Cuban professor at the University of Pittsburgh who

writes about race in Cuba. "It became a scandal." The incident,

he says, reinforced Cuban stereotypes about Spanish racism. More complaints

have surfaced at other luxury hotels, yet de la Fuente says the conflict

runs deeper than simple Spanish prejudice. "Cubans themselves also

accept the false narrative of buena presencia, the idea that being white

is more attractive."

As with any family linked

by bloodlines, language and a turbulent history, this ambiguity is par

for the course in the Spanish-Cuban relationship. In the 1800s, when

American colonies began to revolt against the mother country, Spain

dubbed sugar-rich Cuba the "ever-faithful island" and trusted

she alone would never stray. Losing this favorite daughter to the United

States in the 1898 independence war was a psychological disaster for

Spain. "Like losing a limb," explains Coso at the Spanish

Cultural Center. Even today, Spaniards recognize the historical impact

of Cuba's liberation. "Don't worry about it, more was lost in Cuba,"

they are likely to remark when something goes wrong. Cubans, who study

Spain's violent war campaign in history class, enjoy their own humor

about Spanish business people relocating to the island; they joke that

Spaniards are back to get what they lost in 1898.

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

But today's Spaniards are

arriving by airplane - not ocean vessel - and importing cash, new ideas,

and high hopes of becoming Cuba's most trusted business partner. It

wasn't always this way. In colonial days, Spaniards who emigrated to

Cuba had little to offer. María del Carmen Molina, the Cuban

granddaughter of Spanish immigrants, shakes with laughter remembering

a television show she watched as a child during the early days of Cuba's

Revolution. The program poked fun at those early Spanish immigrants

who - fleeing Spain's economic depression - arrived in Cuba penniless

and had to prove themselves. But time has turned the tables and today

all that is Spanish is the ticket to success. "Now everyone wants

to be Spanish," Molina laughs.

There is more truth than

irony to her remark. If Afro-Cuban dance and music have captivated the

world in recent years, there are still more practical advantages to

having Spanish heritage than African roots in today's Cuba. It all began

in the early 1990s, when Spain's socialist government pledged generous

humanitarian aid to the struggling island. In Cuba's most desperate

hour, Spain also recalled its shared blood lines with the island. Prime

Minister Felipe Gonzalez made more Spanish passports available to Cubans

of Spanish descent, and with that move old bonds re-awakened. Across

the island, light-skinned Cubans rushed to sift through family documents,

searching for birth certificates and letters - anything to prove a direct

family connection to Spain. Ramona Alvarez, Molina's mother, was one

of them. The Cuban-born daughter of Spaniards applied for a Spanish

passport in 1994, when food was scarce and the future looked bleak.

Little did she realize her quest would span five years and be overshadowed

by another bitter fight between the two nations.

As Alvarez began her application

procedure in Havana, Spain was undergoing a dramatic political shift

that came to a head in 1996 when the conservative José María

Aznar took power. With his election, Spain withdrew most of its financial

assistance from Cuba and called for political reform on the island.

Things heated up even more when Aznar named José Coderch as his

new Ambassador to Cuba. While still in Madrid, Coderch informed Spanish

newspapers that the minute he arrived he would "throw open the

doors" of the Spanish Embassy to Cuban political dissidents. Furious,

the Cuban government refused to let him set foot on the island. But

rumors spread quickly, and hundreds of Cubans stormed the Spanish Embassy

in hopes of getting a visa. Cuban officials had to send police-backed

construction workers to cordon off the building. Political ties snapped.

For more than a year afterwards,

the Spanish ambassador's office in Havana stood empty. But ultimately

business sense prevailed. With millions of dollars already sunk into

the Cuban economy, Spanish investors upped the pressure on Aznar and

his conservative pro-business party, Partido Popular. For their part,

island officials maneuvered to protect the fragile economy by making

overtures to Spanish executives. It worked. In 1998, a 100-member contingent

of Spanish business executives arrived in Cuba. At the same time, Aznar

announced Spain would loosen its purse strings and increase humanitarian

aid.

| Time

has turned the tables and today all that is Spanish is the ticket

to success. "Now everyone wants to be Spanish," Molina

laughs. |

Meanwhile, Spanish-owned

Iberia airline stepped up its weekly flights to Cuba in anticipation

of increased tourism and business travel. Finally, Spain's new ambassador,

Eduardo Junco, arrived on the island amidst talk of "a new era

in Spanish-Cuban relations".

This tentative reconciliation

directly benefited Cubans like Alvarez. After five years of waiting,

she finally received the cherished passport – and with it some

perks. One of them is status. "Now she's Doña Alvarez, instead

of compañera," the lively Molina says playfully. She shoots

a glance at her mother, who obliges by lifting her head with a little

nod. At age 75, Alvarez has no illusions of actually setting foot in

the land of her ancestors. "If I could travel to Spain I probably

would, but it's unlikely now," she muses, settling back into her

rocking chair after disappearing into the bedroom to retrieve her passport.

"But I wanted this for sentimental reasons," she says, caressing

the small yet valuable booklet.

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

Sentiment aside, the pocket-sized

object also represents a better standard of living. In the last few

years, Spain has begun offering pension money to its foreign citizens

over age 65 in Cuba. "The announcement was like an explosion in

Havana," says Molina, who waited - with about 1,000 other people

- to apply for her mother's pension money last year. On average the

pensions range from $500-800, which is equivalent to winning the lottery

in a country where the average income is $12 a month. As a direct result

of the pension offer, the number of people applying for Spanish passports

has nearly tripled since 1998, to 6,000 in 2000. But while the money

provides welcome financial relief, it only highlights the deep economic

divide between Cubans and Spaniards.

"It broke my heart

to see doctors and teachers - educated people -waiting there for Spanish

charity," Molina says, watching her mother's aged face, serene

under a halo of white hair. Still, measured by the number of people

who line up outside the Embassy, Cubans are eager to accept Spain's

offer.

Elvis Mendoza's eyes are

glazed over by the time he reaches the shady gardens of the Spanish

Embassy. He is squeezed uncomfortably onto a narrow wooden bench next

to a sunken old woman nodding off in the stifling heat. Nearly 300 miles

separate the capital from Mendoza's rural home in the tobacco-growing

region of Sancti Spiritus. This time his journey spanned 24 hours. The

adventure included a delayed train, a broken down bus, and a communal

taxi crammed to capacity. Now inside the gates of the elegant mansion

– one of Havana's few restored colonial buildings - the shy man

is giddy with nervous energy and entirely out of his element. Still,

his mission lends him strength; Mendoza's aging mother has a Spanish

passport and needs money. The Spanish Embassy's humanitarian aid program

is her last hope. "My mother sent me instead of my brother,"

Mendoza jokes, "because he's even more guajiro than I am,"

he says, using the affectionate name reserved for country folks from

the provinces.

Mendoza is the living legacy

of Spain's roots in Cuba. His Spanish-born grandfather immigrated to

Cuba in 1917, among the last wave of Spanish immigrants destined for

the island after Spain lost the war. Like him, one-third of the 3.5

million Spaniards who left Spain between the late 1800s and 1930 were

destined for Cuba. "They were attracted to a place where there

are still family connections," explains Joaquín Roy, a professor

of Spanish-Cuban relations. On the island, Mendoza's grandfather raised

his family with Spain in his heart. He told stories to his grandson

about peasants working the dry earth in Extremadura, of Arab palaces

among olive trees in the south, and of gruff fishermen in northern Galicia.

Mendoza has never been to Spain, but says he has imagined it all his

life. "Because of my grandfather, I've always felt very Spanish."

But this journey to the capital is for practical rather than nostalgic

reasons. Mendoza's family has heard about the pension money and he is

in Havana to claim his mother's birthright.

| "It

broke my heart to see doctors and teachers - educated people -waiting

there for Spanish charity," Molina says, watching her mother's

aged face, serene under a halo of white hair. |

Mendoza has a lot of company.

In 2000 alone, 3,200 Cubans were registered to collect the Spanish pension

money. Most days, long lines of people snake down the sidewalk outside

the Spanish Embassy a block from the Malecón waterfront boulevard.

Some pace to break the monotony. Others animatedly compare family histories

and commiserate about the wait. A 17-year old named Fernando shows a

generous smile as he reclines against the building, ducking out of the

slant of mid-morning sun already threatening to boil the pavement. He

says his family has been to the Embassy several times in the past seven

months. "Here we go again," he grins. Nearby, Fernando's mother

holds their place in line, patient in her bright flowered dress that

pulls a bit too tight in the arms. She clutches faded documents - a

birth certificate and letters - that could pave the way to Spanish citizenship.

For those around her – whose other option is the dangerous 90-mile

water passage to the United States – a Spanish passport offers

a legitimate way out of Cuba provided they can somehow afford the airfare.

It's a legitimate path,

but often long-delayed. Most business requires much bureaucratic paper

pushing and shifting feet in line. Still, Cubans arrive and wait –

something to which they are long accustomed. Just around the corner

from where Fernando and his mother stand winds another line of people.

This one is reserved for married couples trying to get a travel visa

for the Cuban spouse. In line are all types; middle-aged couples who

have been married for years in Cuba and simply want to visit family

in Spain together; fresh-faced newlyweds; and older Spaniards with young,

dark-skinned Cuban women – an increasingly common image in Havana's

dollar-run tourist bars and nightclubs.

For Cubans like these with

no Spanish bloodlines, the doorway out is often through marriage –

a process that can be just as frustrating as applying for Spanish citizenship.

Couples schedule numerous interviews at the Embassy, often waiting for

hours. Even with the hassles, Spain remains a popular destination for

love matches these days, in part because of language and historical

ties. Beginning in the early 1990s when the economy plummeted, Cuban

wives and lovers began turning up in Spain. Today, some 3,000 Cubans

who are married to Spaniards apply for visas each year. This compared

to just 15 yearly applicants a decade ago, says María Cruz Arias

of the Spanish Consulate in Havana. The dramatic rise, Arias says, has

coincided directly with the tourist boom. Some marry for love; some

marry to escape the island. Still other Cubans find their way to Spain

each year through study exchanges, training programs, and business connections.

In 2000, nearly 300 Cuban students were awarded study grants to travel

to Spain. Once there, many never return to the island.

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

Beatriz Ávila is

not going back any time soon. She arrived in Spain with a four-year

study grant from the Spanish government and quickly found a well-paid

job in a private clinic. Though she now calls Spain home and has applied

for residency, she admits frustration over Spanish stereotypes of Cubans.

"Most Spaniards only think of Cuba for its famous sexual tourism,"

she says by phone from Madrid. "Sometimes when I meet people here

in Spain, they make offensive comments about Cuban women." Still,

Ávila says she doesn't see herself fitting back into the pattern

of Cuban society after having been away so long. For her, Spain is the

next best thing, given the two nations' intimate relationship. Many

Cubans apparently agree. The community grew quietly after the fall of

the Soviet Union, and by 1996 there were 7,000 Cubans living in Spain.

Today, there are about 16,000, making Spain home to the largest Cuban

community outside the island after Miami. There is no doubt the European

nation has a nostalgic pull. Castro himself is the son of Spanish immigrants,

and in 1984 he made a historic visit to the remote northern region of

Galicia where his father was born. Castro's ex-wife and daughter both

live in Spain, as do an ever-increasing number of artists, writers,

athletes and political dissidents.

But leaving the island is

not the only desire fueling the relationship between Cuba and Spain

in recent years. There is no denying each has something the other wants.

No one knows that better than Eusebio Leal, who as Historian of the

City of Havana is one of the most powerful men on the island. On a humid

afternoon in his Old Havana office, he faces a dozen wide-eyed visiting

student architects and poses the question: "Which is more important:

food or beauty?". With no hesitation, he answers himself: Beauty.

Yet Havana's beauty is ravaged by time; those early Spaniards would

barely recognize the Caribbean gem they so loved. Its splendor is tarnished

by peeling paint and gaping cracks. The ocean knocks relentlessly against

the Malecón's rocky sea wall, its salty spray licking buildings

and warping facades. If the sad image tugs on proud Cuban hearts, it

has an equally strong effect on Spanish sensibilities. After all, Spain's

history lives in the island's architecture. "For all our projects

we need money, lots and lots of money," says the beige-clad Leal,

his voice resonating through the corridor of a room. Spain is one of

his biggest collaborators. In addition to the newly-restored colonial

Spanish Cultural Center, money from Spanish regions is being used to

restore sea front homes all along the Malecón. Cuban men and

boys mix cement under the glaring sun at construction sites as vintage

Plymouths speed by, pausing only to pick up pretty young women hitching

rides. The projects are collaborative; Spain provides the funds and

Cuba provides the manpower. But like most joint ventures, there are

bumps in the road. Leal says frictions occasionally arise when Spain

tries to exert too much control. Still, Cubans know to tread lightly

where cash is concerned. "We have to pursue money where we can

get it," Leal states matter-of-factly.

Spanish generosity extends

beyond architecture. By late 2001, a long-awaited Spanish-funded water

project – restoring the century-old Albear aqueduct - will provide

16 percent of Havana's residents with purified drinking water. Spain

is also Cuba's most enthusiastic partner in cinematography. The European

nation funds half the films made each year on the island and finances

extensive archival restoration.

This new level of collaboration

between the old colonizer and her dearest colony is sparking some unusual

partnerships. In one of Havana's restored colonial jewels, Cuca Llagostera

now holds court. Wearing a stylish linen suit, the petite blonde looks

dressed for a chic downtown venue in Madrid rather than a quaint hole

in the wall in Old Havana. But then she throws on an apron, casually

snuffs out the cigarette dangling from between her lips, and heads for

the kitchen. There she whips up Spanish tortillas and fried garbanzos

in one of two restaurants that she manages with a Spanish partner in

the heart of Havana's tourist zone. At the Mesón de la Flota

restaurant, Spanish wines are stacked along the wall: Merlots from Barcelona,

Solmayor from La Mancha, and the occasional local wine from Pinar del

Rio province. Two Cuban waitresses gossip at the bar, their curls twisted

up inside identical flower wreaths.

| "The

Spanish business people in Cuba aren't interested in cultural associations,"

laments Barros Lopez. "It's like we live in two separate worlds." |

Though she is one of an

estimated 10,000 Spanish citizens who have recently immigrated to the

island, Llagostera's story differs from that of the typical entrepreneur.

She ended up in Cuba with her husband, who works in a joint business

venture in shipping. That water theme is everywhere. A miniature ship

model rests above the bar, and fishing nets drape gracefully next to

filmy black and red flamenco shawls on the pale walls. A sign outside

advertises the restaurant as "4,000 nautical miles from the point

of departure," playing off the image of the Spanish conquistadores

who reached Cuba by ship in the 1500s.

"The sea here reminds

me of Spain," says the Barcelona native, at home in her new surroundings.

A slow smile creeps across her calm, sun-tanned face at the suggestion

that she is setting a new trend for Spanish women in Cuba. "We're

definitely pioneers of a sort, my partner and I. There are very few

others doing what we've done here with the restaurants." Downtown

regulars, businessmen, and tourists keep the kitchen staff busy, and

Llagostera greets local patrons warmly, joking with her young, attractive

Cuban staff. Still, Llagostera's point of reference is always Spain.

"Most of my friends here are Spanish," she says. "We

usually get together at each others' homes or at restaurants and form

our own social groups." Many of her compatriots feel the same way.

Pereda from the hotel in Varadero maintains his loyalty to Spain, even

after 11 years in Cuba's tourist industry. He vacations in the cool

green hills of his native land in northern Castille and León,

and prefers Spanish matadors to Cuban baseball stars. As part of a new

generation of Spanish expats mainly focused on business activities,

it benefits them all to remain connected to the powerful Spanish business

community.

And their children follow

suit. Even as Spaniards mingle with Cubans on a day-to-day basis, they

still maintain distinct separations. Across town from Llagostera's restaurant,

in the peaceful, tree-lined Miramar neighborhood, is the Spanish School.

"It's just as if the students were in Spain," explains Javier

Rivera, the school's charismatic young Cuban director. Here among foreign

embassies and diplomats' homes students study a strict Spanish curriculum.

Exams are sent to Spain to be corrected, and students must wait weeks

to get their results back by mail. "It's not the best system for

the students," Rivera concedes, "but the instruction is excellent."

While the basics of math

and science vary little, Rivera says Spanish and Cuban education systems

part ways where philosophy and history are concerned. Greek philosophers

like Aristotle and Plato reign in the Spanish School, while Cuban kids

study Stalinist theory. And while Cuban students, in their tidy yellow

and red school uniforms, memorize the island's history, the Spanish

curriculum focuses on world history. "Unfortunately, they don't

have time to study the history of Cuba, the country in which they reside,"

Rivera says. The majority of the Spanish students – who comprise

nearly half of the entirely international student body - are the children

of business executives. "If the business goes well, they don't

leave," Rivera says. Things are going well. The school opened with

16 students in 1986; it now boasts 140. In a country where education

is free, the Spanish School's price tag is far beyond the average Cuban

family's reach. The two groups, for the most part, remain separate.

"Spanish kids only integrate into Cuban society if their parents

do," says Rivera, whose own daughter cannot attend the Spanish

School because she is Cuban. Smiling through cigarette haze at her restaurant,

Llagostera puts it more bluntly: "When you are very far from Spain,

it's natural that you would want to spend time with other Spaniards."

|

"Each

year the assistance packages are a little smaller," Barros

Lopez says, referring to the packages of soap, food and presents

that used to arrive from Spain.

In

the midst of the Spanish investment boom on the island, Barros

Lopez confides, "I don't see a bright future for the cultural

associations."

|

Although that comment would

make him flinch, Jesus Barros Lopez, president of the Galician Association

in Havana, also knows it's true. Part of the problem is economics, but

part is that the Cubans who strongly identify with their Spanish roots

are an older generation than the fast-paced peninsulares. Only a few

miles across town from Llagostera's restaurant - but eons away - is

the Galician Cultural Center, one of more than 100 Spanish cultural

associations that still exist in Havana. "The Spanish business

people in Cuba aren't interested in cultural associations," laments

Barros Lopez. "It's like we live in two separate worlds."

And they do. While Llagostera and her contemporaries enjoy going to

clubs and socializing at private parties, the 83-year-old Barros Lopez

spends his Saturday evenings at cultural presentations in the stately

mansion that houses the Center on the corner of the Parque Central.

Up a sweeping stairway,

in a cool, cavernous room far removed from the bustle outside, a few

older men are gathered at a table talking club business; dues, gaeta

music workshops, and the weekend event in the great salon. Galician

historians, poets and politicians peer out from wall paintings. Two

flags – one Galician, the other Spanish - stand at attention. "Gallego!"

one of the men suddenly shouts. From a raised platform at the back of

the room, a rumbling voice calls back, "Hold on, I'm busy."

Barros Lopez smiles. "They call me Gallego, but I'm Cuban born

of course. None of us is really from Spain anymore. We're just the sons

of Gallegos."

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

Wiry and gently bent with

age, Barros Lopez presides over a desk in danger of collapse. His hand

taps a pile of history books and board games, punctuating each word:

"There is less and less Spanish cultural presence in Cuba."

Not so in the old days. In its heyday, the thriving Galician Center

boasted 60,000 active members. But following the Cuban Revolution in

1959, cultural centers all but died out as the Cuban government aggressively

promoted unity through nationalism. The situation shifted again during

the financial crisis of the early 1990s. In the ensuing years, Spanish

associations resurfaced as important funnels for monetary aid to Cubans.

Consequently, association membership began to grow. "We've been

locating Spanish descendants all over the island," says Bruno Leyva

at the Andalusian Center, a short walk down the Paseo del Prado from

the Galician Center. "Many don't even know they have a right to

be a member." These efforts seem to be paying off. The Andalusian

Center's membership jumped from 400 in 1997 to 650 today. But the members

belong to a younger generation with little direct connection to Spain.

To maintain ties, a small number of older Cubans travel each year to

Galicia, funded by the Galician government. But people are dying off.

"Each year the assistance packages are a little smaller,"

Barros Lopez says, referring to the packages of soap, food and presents

that used to arrive from Spain. In the midst of the Spanish investment

boom on the island, Barros Lopez confides, "I don't see a bright

future for the cultural associations."

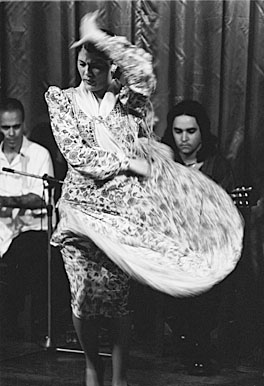

Most Cuban schoolgirls,

however, would be devastated if the centers closed. Of the many aspects

of Spanish culture, traditional dance is thriving on the island. After-school

flamenco class is the latest rage. Thirty pony-tailed little girls whirl

like dervishes on and off a narrow wooden stage at the Andalusian Cultural

Center. The mad clacking of castanets combines with the feverish pounding

of high-heel dance shoes and the swish swoosh of multi-colored ruffled

skirts. A soloist steps to center stage, her face as proud and pained

as any flamenco diva in Spain. The harried instructor in her matching

vest and mini skirt, barks, "Arms! Watch the arms!" while

rotating her wrists like fans, her fingers painting the air. The older

girls imitate her, faces pinched in concentration, while the younger

ones tickle each other in the wings. "Silence!" the teacher

shouts, mouthing around her fifth cigarette. Attempts at another remonstration

fail along with her voice. "Next time somebody bring me a microphone,"

she rasps.

No one is listening anyway;

the Cuban mothers watching from the street through open windows are

as swept up as their daughters in the haunting boleros and playful Sevillanas

crackling over the loud speakers. Eleven-year old Johanna takes breaks

every five minutes to pose and wave to her mom. "I've been taking

classes since I was six," she says proudly during one of her visits

to the window. Johanna is Afro-Cuban, and lured - as are her companions

– by the novelty of Spanish dance.

But no Spanish girls are

dancing with the Cubans on stage. "They don't go to flamenco dance

classes," says principal Rivera from the Spanish School. "Their

parents are more interested in practical activities – like English

classes."

Back

to stories page