The

town that time forgot:

An example of socialism

in Cuba's tobacco industry

by Daniela

Mohor

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

The warm smell of tobacco

floats in the room. Wooden tables covered with piles of tobacco leaves

are lined up. Sitting at their desks like children in a classroom, more

than 100 Cubans hand roll some of the world's most sought after cigars:

Montecristo, Cohiba, Romeo y Julieta. As they work soft wrapper leaves

over rougher tobacco, they listen to a morning radio sitcom.

"The man's face is the face

of a dog," says a deep and manly voice. "It's a threatening face."

No one pays much attention.

Instead, workers chat among themselves. While they joke, even holler

across the room, their fast fingers effortlessly grab the brown leaves

and shape the cigars. Despite the daily production quota of more than

100 cigars per worker, the atmosphere is relaxed and friendly. Most

of the hand-rollers are young, have known each other since childhood,

and appear happy to be there. The opening of the factory has made their

life easier.

Inaugurated in January 2000

in the small town of Pilotos, about three hours southwest of Havana,

the Juan Casanueva factory, named for a local martyr of the revolution,

is the direct result of a local initiative and the latest expression

of the community's strong support for the revolution.

The factory became a reality

when a group of tobacco growers from the town's agricultural cooperative

made an uncommon move. They went to Fidel Castro and asked him to transform

the abandoned military base into a cigar factory. They had two purposes:

to create new job opportunities to keep young people in town, and to

serve the revolution. Castro liked both.

Pilotos' new factory is

one of 60 cigar operations that are playing an increasingly significant

role in the country's post-Soviet economy. In the early 1990s, with

the collapse of the USSR and its support of Cuba's economy, the island

sunk into a deep recession. In the span of three years the GDP shrunk

by 40% and the state could not feed its citizens. The crisis pushed

Castro's regime to ease market restrictions and introduce dollars into

the economy. The state too needed hard currency, and so it turned to

the sectors that generated the highest income in dollars: tourism and

export tobacco.

While the price of raw tobacco

is roughly 10 cents per pound, a box of Cuban cigars abroad sells for

as much as $200. The market is profitable, and Castro knows it: new

brands and new sizes of cigars at different price keep appearing and

every season new workers are incorporated in the industry.

For a factory at the cutting

edge of the economy, the Pilotos plant is also a throw back to the best

days of socialism. Everyone has a role to play in the production and

all laborers are equally important. Piñaldo Franco, the director

of Pilotos factory explains, "The country is a single entity, the factory

is a single entity and it has a single owner: Fidel Castro."

| "I

was born under a tobacco tree," jokes Orlando Acosta. "So

I know a bit about tobacco." |

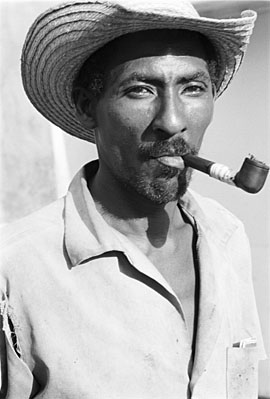

Like many of Pilotos 5000

residents, Orlando Acosta, the factory's production supervisor take

prides in his lifetime of working in tobacco. He is a quiet but friendly

man with a soft voice and a brown moustache. At the factory, people

simply call him Rolando.

"I was born under a tobacco

tree," he jokes in the small storage room where raw material is handed

out to the rollers. "So I know a bit about tobacco."

On weekends, when he can

escape family duties, Rolando goes to the countryside where he still

has a vega, or tobacco field. There, he relaxes and "forgets about work."

Going from growing tobacco

at the local cooperative to managing an industrial factory was no small

task. Rolando and two other cofounders had to learn everything from

selecting and stemming tobacco leaves to hand-rolling cigars and quality

control. For 13 months he attended class in Havana and visited other

factories in Pinar del Rio, the traditional tobacco region where Pilotos

is situated.

By June 1999, they were

ready to open a hand-rolling school in the factory and receive the first

group of workers: 73 people took the first class, including Rolando's

wife. Since then, dozens of new recruits have been selected and trained

every season, contributing to the production's steady increase. Last

year laborers rolled 1.4 million cigars, surpassing their goal by more

than 200, 000 pieces. This year, the factory hopes its 206 workers and

66 students will make more than 2.4 million cigars.

Underlying such efficiency

is the state's new incentive policy. With the crisis, the government

dug up an agricultural law from the late 1980s that permitted independent

tobacco farmers to use idle cropland to grow tobacco.

The state provided other

incentives as well. The government still sets the price of tobacco and

furnishes fertilizer and agricultural supplies, but now farmers are

paid according to their productivity. The more they grow, the more they

earn, and part of their income is in dollars. The same incentives apply

to factories. Workers receive six percent of their wage in dollars and

extra money for each cigar they make above their daily quota. At the

Pilotos factory, some workers have doubled their $16 monthly wage.

All over Cuba, the incentives

have worked: between 1996 and 2000 the number of cigars exported rose

from 70 million to 118 million. And this year, Habanos S.A., the distribution

company for Cuban cigars, plans to ship 150 million.

The significance of tobacco

in Cuba, however, goes beyond its potential to save the island from

the dollar crisis. Tobacco is to Cuba what scotch is to Scotland.

|

|

photos

by Daniela Mohor

Men roll cigars

at the Pilotos plant.

|

|

"Talking about tobacco is

talking about the national cultural identity," said Zoe Nocedo, the

director of the Museum of Tobacco in downtown Havana. "It is not only

a fundamental product for the economy, but a product that helped the

development of the history of Cuban culture."

When Cubans don't want someone

to expand for hours on a topic they say: "Don't tell me the whole history

of tobacco." And they have good reason.

By the time Christopher

Columbus discovered Cuba in 1492, the Indian natives had already organized

all their rituals around the tobacco tree or "cohiba." They smoked to

communicate with divinities and they used the plant as medicine to cure

skin diseases and cuts. Columbus' crew smoked for enjoyment and it didn't

take long for them to send the leaf home.

After unsuccessfully trying

to prohibit tobacco imports in 1717, the Spanish Crown instead decided

to establish a monopoly on tobacco's cultivation and comercialization.

A century later, Cuban rebellions and problems of mismanagement led

to the end of the monopoly and the island developed its own tobacco.

With the creation of the

island's first cigar factories, the tobacco industry took center stage

in Cuban history. To entertain the rollers, tobacco barons hired readers,

who read news and literature from around the world- a tradition that

gave workers the reputation of being the world's most educated.

It didn't take long before

they started organizing and progressively acquired political power.

They participated in all major strikes affecting the country, supported

José Martí's fight for independence and later Castro's

revolution. Nowadays, the reader's fare is limited to Granma, the national

paper, and romance novels.

Back

to stories page