Trinidad, For

Sale

by Julian

Foley

Researcher: Pedro Mosqueda

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

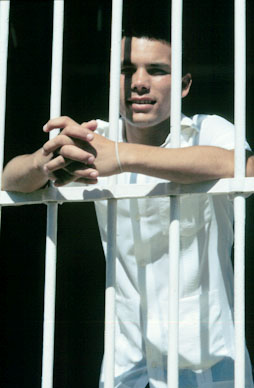

Dany is a jinitero,

a hustler.

Slouching against the white,

wrought iron fence of the Plaza Mayor, he watches weary, sun-burnt tourists

wander in and out of a simple church the Spaniards left behind more

than a century ago. A blue-bereted policeman on the corner watches too,

stoic and motionless. Behind him, a fierce orange sun slips into the

horizon. When its glow fades, he disappears, out of sight. On cue, Dany

is in action. He calls out to a young couple: "Hi, how are you,"

first in English, then in Italian. A "bon jour" finally turns

their heads.

He's on them quick, flashing

a sweet, jaunty smile as he makes his pitch in fluid French. He is afrocubano,

tall and dark, handsome even beneath the dingy tee-shirt and faded red

shorts he spends his days in. The silver rings that weigh on his long

fingers flash bright against his smooth skin. His confidence is contagious.

"I can get you anything you need," he tells the couple: private

lodging for two in a real Cuban home, just $20 a night; a succulent

home-cooked lobster served with fried bananas and fresh green tomatoes

for $5; a guided horseback ride into the nearby Escambray mountains

to visit the magnificent El Cubano waterfalls and swim in its pools.

He absentmindedly snaps his right hand as he talks, trying to add urgency

to his offer.

But the two have their response

ready: They already have everything they need, thanks. He lets them

go. Undeterred, he returns to the fence and gets ready to try again.

Dany is one of Cuba's new

entrepreneurs, and this is the new Cuba. If the people of Trinidad have

something to sell, he will make sure the foreigners– the yuma –

buy it. In return, he gets a cut off the top. And everything is for

sale in this pristine colonial city on the island's underbelly. From

the slew of government controlled resorts, hotels, restaurants, and

shops – even bars and clubs – to the counterfeit cigars sold

from dark corners, a two-tiered, post-revolutionary economy has developed

to divest tourists of their money.

There is no shortage of

pocketbooks. Each day, sleek tour buses wobble over the cobblestone

streets in the town's old center to dump their loads: Europeans, Canadians,

even Americans – package tourists shipped in from the beachfront

resorts on the white sand Peninsula Ancon just twelve kilometers away.

Over the last ten years, tourism in Cuba has grown from a trickle of

Soviets and native vacationers to a $2 billion industry, thanks to a

careful opening to foreign investment. Most of the money goes to straight

to the government – desperately needed hard currency to pay the

island's external debt – but Cubans have found ways – legal

or otherwise – to keep some of it for themselves.

| "Every

country has a national sport," explains Dany – whose name,

along with others in this piece, has been changed to protect his

identity. He grins unabashedly. "Cuba's is looking for dollars." |

"Every country has

a national sport," explains Dany – whose name, along with

others in this piece, has been changed to protect his identity. He grins

unabashedly. "Cuba's is looking for dollars."

Just on the outskirts of

town a luxury tourist bus from Havana rolls into an empty lot. Eager

Trinidadians are already there, pressing their faces to the metal gate

that keeps them out. They know the schedules by heart.

Disoriented and groggy,

I step off the bus just as the din erupts. A taxi driver grabs a couple's

bags and hoists them on board without waiting to be asked. Jineteros

and homeowners wave makeshift white business cards and call out prices

as the foreigners disembark, fighting to lead us to private rooms. "Ten

dollars. It's my house. Very comfortable," one tells me, shoving

his card in my face even after I have brushed him off. Three others

follow me, two on bicycle, one on foot, up the gentle hill into town

in a contest of endurance until finally, two give up, and I reluctantly

give in to the third. The bus stop is just the beginning. The proto-capitalist

cacophony here never quiets.

In the center of town, skirting

the landscaped squares and magnificent colonial mansions that tourists

come here to see, open markets line the narrow, labyrinthine streets.

Vendors wait behind tables laden with crafts – painted gourds,

handmade maracas, and polished wood statues of drummers and dancers

– for spendthrift visitors to wander through. Beautiful handmade

linens, patterns nearly identical, hang one after another along the

curving sidewalks, filling an entire alley with billowing sheets of

white. "Good prices," a woman assures someone who stops to

look. "Fifteen dollars," she says, to get the bargaining started.

"And I'll give you a necklace for free."

|

|

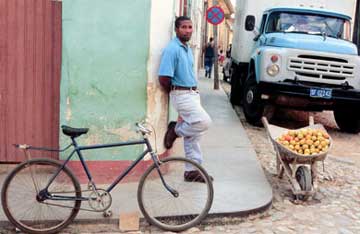

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

The city streets

of Trinidad.

|

Just around the corner by

the tall, brilliant blue wooden doors of the Galeria del Arte, an old

man, white sideburns peeking out beneath a dilapidated straw cowboy

hat, sells photo-ops with his donkey for 50 cents. Selling on the street

has been legal since 1993, but this is hardly capitalism: hefty government

license fees and taxes divert most of these vendor's profits to government

coffers. They pay for the right to sell, regardless of how much is sold.

Unless they have another source of income, one bad season can wreck

them.

So an illicit tourist sector

has developed alongside the legal one, and the jineteros are its tour

guides. "What's worse?" asks Dany's friend Manuel who sells

counterfeit cigars. "Selling cigars on the street, or robbing and

begging? They call us bad names, like pimp, but we are just trying to

make a living."

A living, the people here

will admit only from the privacy of their dining rooms, that the socialist

system – even one bolstered with tourism revenues -- can no longer

provide. Basics goods that Cubans covet, like toilet paper or meat,

are simply unavailable most of the time in the tiny storefronts that

accept the Cuban peso. Instead, they must be purchased in dollars from

the special stores that were initially opened to serve tourists. A government

salary that may have been plenty to live on in the 1980s is today, on

average, worth about $12. That buys about five bottles of vegetable

oil in a country where everything from chicken to bananas is fried.

"If everyone had pesos," says Dany "if I spent pesos,

if you changed money to pesos, it would be fine. The problem is that

everything requires dollars."

He, for one, would like

to return to the days before the "Special Period" – the

years of economic austerity that began when the Soviet Union's collapse

left the heavily subsidized Cuban economy in virtual freefall. "Maravilla,"

a marvel, is how he remembers it. He kisses his hand and blows it to

the wind. But then, he was only ten when it started.

Dany, like most in his field,

prefers to work at night, when the darkness provides cover from anyone

who might be watching: police wandering around their quadrants, looking

for trouble-makers, or the Committee for the Defense of the Revolution

(CDR) representatives – neighborhood spies – sitting on their

stoops keeping an eye on the streets. He knows where they are and is

careful to avoid them, even though some people say they aren't as watchful

as they used to be.

| What's

worse?" asks Dany's friend Manuel who sells counterfeit cigars.

"Selling cigars on the street, or robbing and begging? They

call us bad names, like pimp, but we are just trying to make a living." |

Hungry tourists looking

for a good meal are his easiest prey at this hour. Tonight he positions

himself at the bottom of the escalera – the wide stone staircase

next to the church that unfolds onto the sloping town below. A dominoes

game in the street has attracted a small crowd. Lively salsa lures foreigners

up the steps to an outdoor bar; further up is a terrible state-run restaurant.

Both sell in dollars only, and it is rare to see a Cuban there who isn't

serving or performing. So Dany doesn't mind stealing their business.

And he knows he offers a superior product.

With a sharp eye, he spots

an Italian couple he found dinner for the night before and sidles up

beside them. "You want to eat?" he asks in an animated whisper,

slipping his arm around the man's shoulders. They remember him and pause

to hear him out, laughing to each other at his persistence. His irresistible

grin and impressive high-school Italian wins them over again. "Come

on," he says, motioning, and they follow him obediently, trustingly,

as he steers them towards the dark streets behind the Plaza. He stays

a pace ahead of them to avoid suspicion, and his eyes never stop moving.

"There is a lot of

fear here," he told me. And some say racism, too, despite the official

words to the contrary. Manuel thinks that he and Dany get questioned

by police more often than white jineteros because of their dark skin.

But Dany disagrees. "We just stand out more when we are walking

with the tourists," he says. "White Cubans blend better."

He glances over his shoulder

one last time before he leads the Italians into the living room of a

private home. Two women watching television don't even look up as they

pass through into the tiny, badly lit dining room of this unlicensed,

illicit paladar. Dining rooms like this are hidden all around the tourist

part of town, behind colonial Cuba's trademark mélange of pink,

blue, or green wooden doors. Some paladares are legal, but the license

is prohibitively expensive for Cubans who only have enough room in their

tiny houses to seat eight to ten guests. Dany's services, a mere dollar

or two per guest compared with up to $500 per month for a license, are

cheap. So most who serve food to tourists do it quietly, and keep it

small enough that the CDR are willing to let it go.

Dany stays only a moment

to see his charges seated at one of two rickety tables – mismatched

plates, silverware, and scratched glasses laid out on a plastic tablecloth.

"They want lobster," he whispers to the woman of the house.

"I told them five dollars." He'll get his cut later. Within

seconds, Dany is back out on the street, looking greedily for his next

catch.

Dany's other big moneymakers

are the casas particulares, the private homes in which Cubans rent out

rooms to more budget-conscious tourists. Most are licensed, but proprietors

who do not have the time or nerve to go out into the street to find

their own customers still have to pay Dany a $2 per night for every

guest he delivers. This, on top of the $150 per month per rental room

for the license and 10 percent yearly income tax they pay the state,

means scarce profit. The government justifies the fees by the heavy

housing subsidies every Cuban receives, but many people have to secretly

rent out additional rooms or sell egg and papaya breakfasts to their

guests just to afford them.

The town is teeming with

jineteros tonight, jockeying for untapped tourists. David, tired

and grungy-looking beneath his 5 o'clock shadow, is trying to pull in

anyone Dany hasn't gotten. In another life he'd be a scientist. He studied

geophysics for three years before the Special Period began and he had

to give it up to work. At 31, he doubts he'll go back to school, but

he hasn't stopped reading and studying on his own. He has plenty of

ideas, like almost everyone here, about what the dollar economy means

for Cuba's future.

"The government knows

that Cubans are inventive and that they will find a way to survive,

but shhh," says David, leaning across the table in a dingy paladar,

whispering. He thinks a little extra money making has been tolerated

as a safety valve for discontent as long as it's kept quiet. But it's

a theory no one in Trinidad wants to test. The 1500 peso -- $75 dollar

– fine for selling anything without a license, be it a taxi ride

or a steak dinner, is enough to keep everyone on edge. And Cuba has

its own three-strikes law – on the third fine, it's off to prison.

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

But now that the economy

is picking up, David fears the government is trying to phase out the

entrepreneurial class, and him and Dany with it. There are eight new

luxury hotels in various stages of planning and completion rising up

on the peninsula to accommodate an influx of visitors that has been

increasing by 5 to 10 percent per year since 1995. Names like Sandals

and SuperClubs of Jamaica, even Club Med, have teamed up with Cuban

companies to fill in the island's spectacular beachscapes with all-inclusive

resorts and five-star restaurants. In theory, the tourists will have

everything they need at these new hotels – lobster, air conditioned

rooms, guided horseback rides and scuba diving, even painted masks and

woven straw bags – and all of their dollars will go to the investors

and the state.

"It is very difficult

to get a small business license now" David says – licenses

that many of the jineteros use as a cover for their real work -- and

the government is supposedly cracking down on the people who wait at

the bus station to greet potential customers.

For now, though, there are

plenty of tourists to go around, even towards the end of the peak November

through April season. Dany has made three sales tonight. In addition

to the Italians he took to dinner, he dropped a pair of Americans at

the most expensive paladar in town, and found rooms for them too. All

in all, a pretty good evening.

And as for any twenty-something,

a hard day's work means a night of play. Dany lopes up the hill behind

the church, through a labyrinth of barely-lit streets towards home,

to change out of his dirty sneakers and sweaty clothes. The underground

tourism economy is still in full swing in this part of town. He passes

a guy standing in his doorway who offers "real Cohibas, just like

Fidel smoked" to every passerby. "My mother works in the factory,"

he whispers to the unwitting tourists. More likely, the guide books

will warn you, they are fakes, rolled from the tobacco sweepings that

ended up on the factory floor. Dany, however, insists he can get the

real ones, but says he only offers them to tourists he has befriended.

He arrives on his sagging

doorstep and squeezes through the chicken wire gate in no time. High

up on a dusty road where the cobblestones have faded into dirt, this

tiny house his father built long before the revolution is too far from

the Plaza Mayor to be part of the government restoration plan. The whole

town is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, but although a good portion of

the tourism revenues go towards maintaining its genuine Cuban character,

most is reserved for the tourist sector. So Dany is financing his own

restoration project. His overgrown side yard has already given way to

a bare gray cement skeleton that will one day be a new house for the

two of them.

His mother isn't around

anymore. She was only 23 when he was born and wasn't ready to settle

down with his 62-year-old father. Now she lives in Cienfuegos, about

an hour from here by bus, and has a new family.

|

Dany

pulls his dog-eared Union of Young Communists (UJC) card from

his wallet and holds it up to the light.

"It

means I am an exemplary youth," he says, smiling.

|

From outside the door Dany

can hear the Soviet-made radio crackling from the dining room, where

in a dark, cluttered corner, his father sits with his eyes closed, rocking

slowly in his time-worn chair. The bedroom father and son share is the

only other room, save a small entryway and a crude kitchen. A pot of

thin bean and squash soup is already heated up. "He is a good son,"

says Dany's father, getting up from his chair. At 84, he is still fit

beneath his brown wrinkled skin from a lifetime of cutting cane. His

smile is bigger than Dany's as he lifts his eyes toward the ceiling,

as if to thank God for his good fortune.

Dany sits down at an old

wooden table covered with dirty white canvas. "I am twenty-two

now," he says, his voice tinged with frustration. "I probably

won't be finished building until I'm twenty-six or twenty-seven."

His brother, who might have helped, is in prison for "evading work."

Dany could go to jail too, if he gets caught doing what he does, but

he won't get cited for being idle. He is still considered a student

while he waits to be admitted to the nearby National System for the

Formation of Tourism Professionals (FORMATUR) school.

Even though he has been

making a decent living in the last year, the $40 or $50 a month he makes

on the street is not enough to buy the dollar-only cement he needs to

complete the house. For that, he'll have to go to work in the formal,

government controlled, tourism industry of high-class restaurants and

luxury hotels – these days the most lucrative job a Cuban can hold.

| "There

are many people who just sit around and beg tourists," says

Aragon, the white-haired 78-year-old who rents his donkey for photos.

"I myself don't believe in begging, but if a tourist wants

to give me something, that's different." |

Dany pulls his dog-eared

Union of Young Communists (UJC) card from his wallet and holds it up

to the light. "It means I am an exemplary youth," he says,

smiling. And, he believes, it is his ticket to a real job in tourism.

"I'd like to be a tour guide," he says, "because I love

learning the languages." And traveling the country, meeting people

from around the world, staying in nice hotels, eating good food, and

most importantly, earning dollar tips.

The school Dany has his

future riding on is one of twenty-two FORMATUR schools in the country

that train Cubans of all ages and backgrounds – from highly educated

professionals changing jobs to recent high school graduates – to

serve food, make drinks, sweep floors and greet guests. The training

is mandatory for job placement even in the lowest tier of the tourism

industry. The school also prepares the select few who prove their worth

for management positions in one of the five independently operating

tourism companies that fall under the government's tourism ministry.

The really lucky ones go from FORMATUR to one of the Spanish or Canadian

companies that have joint ventures or management contracts in hotels

around the island.

Unless a student enters

the program straight from secondary school, getting in is no small feat.

Applicants need a graduate degree, recommendations from the local CDR

representatives, teachers and employers, and all of the things typically

associated with university admissions. They will also have to pass tests

on politics, economics, geography and history, and be screened and intensively

interviewed by a psychologist.

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

"This is a very selective

process," says Jose Irarragorria Leon, the Secretary General of

Trinidad's 600-student FORMATUR school, gesturing at the piles of papers

on his disheveled desk. And given the high demand, it has to be. Irarragorria

has no doubts about applicant's incentives: "What would you rather

do, be in the hot sun picking fruit, or would you rather work in tourism?"

he asks, lighting up a filter-less cigarette in his cramped and stale

office. But he denies that only the most committed communists are offered

the opportunity to choose. "We try to find the best students. If

a person comes straight from jail, would you want them to manage your

new hotel?" he says defensively.

But that is not the government's

only concern. If it were too easy to work in tourism, everyone might

do it, draining other sectors like agriculture and education, where

salaries are paid in pesos. In the mid-nineties when Cuba's drive for

tourist development began in earnest, surprising numbers of highly educated

people left their jobs in education and engineering to clean toilets,

sweep floors, or serve beer in the new tourist resorts in Varadero and

Jibacoa. If a maid earns an extra $30 in tips in a month, she has tripled

her government salary. And it isn't just the cash. Employees get other

perks too, like jabas, the monthly baskets of food and personal items

that are only available in dollar stores – good cuts of meat, shampoo,

lotion. There is ample opportunity for cheating, too. A bottle of rum

only costs three dollars at the dollar market, and a mojito -- the lime,

rum and mint drink that is Cuba's trademark -- sells for two dollars

at any bar. An enterprising bartender could easily bring his own bottle

to work and pocket the money from the drinks he makes with it.

Dany suspects that, given

the high demand for tourism jobs, the people who run la bolsa, the lottery

system by which FORMATUR graduates are selected for job interviews,

can be bribed. "Give them fifteen dollars," he says, "and

they'll pull your name." He'll get to test his theory after he

graduates, if he dares.

"Sure tourism brings

in a lot of money for the state," says David, who is surprisingly

candid in his criticism, "But it also brings money to those who

can get it, and that breeds corruption."

But if tourism money is

creating new temptations for people in privileged positions, it is also

reinforcing the loyalties of the people who have access.

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

"Everything is perfect

in Cuba," says Eduardo Ruiz, who says he earns an extra $30 or

so dollars in tips each month driving tourists to the beach and back

in a bright yellow, egg-shaped, open-front taxi. "When you want

a house, they give you a house. No one sleeps on the street here,"

he says.

David, who lives in a tiny,

bare, cement-floored apartment knows it isn't so black and white. He

and his wife pay ten dollars a month to escape his extended family.

Scraping enough money together for rent isn't easy. For him, everything

is hardly perfect.

"Es una imagen,"

he says of the Cuban ideal – a facade, a mirage. He still takes

pride in the benefits socialism has brought to Cuba – good education

and free healthcare the most obvious among them – but he is not

blind to the contradictions the dollar economy has created.

On the street that runs

behind the escalera, a barefoot young mother, bowing with the weight

of a wide-eyed baby that clutches her side, spends her afternoons asking

tourists for money to buy formula. All over town, parents and teachers

are worried about their children, who have already figured out that

tourists are walking candy dispensers. And then there is Maria, a hunched

old woman with no front teeth who walks around most days begging tourists

for dollars and neighbors for used cooking grease.

"There are many people

who just sit around and beg tourists," says Aragon, the white-haired

78-year-old who rents his donkey for photos. "I myself don't believe

in begging, but if a tourist wants to give me something, that's different."

But then, he is fortunate enough to have a donkey at his disposal.

Maria isn't so lucky. She

doesn't have a donkey to photograph, an extra room in her house to rent

out, or an old American car to offer tourists illicit rides in. "I

have always been poor," she says, scurrying off nervously, as if

that were explanation enough. With a government ration card that only

provides enough beans to last a week, it is easy to see where the fault

lines are in Cuba's new economy.

"Before the Special

Period, you could eat perfectly well, just with pesos," says David.

"You could buy clothes, too. But now, prices keep going up and

up." He blames the dollar economy for that.

But for people like Eduardo

who have dollars, the good life is not an illusion. The division between

the dollar-rich and the dollar-poor is visible on any street. Bright-white

Adidas sneakers stand out against worn-out loafers. Well-off kids in

their drab yellow school uniforms crowd into a dollar market in the

tourist part of town to buy sodas and little packages of cookies or

candies. Flashy watches and gold chains are conspicuous next to naked

wrists and callused hands.

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

Seventeen-year-old Chuchy

is the essence of the new consumer. She has had her heart set on a career

in tourism for years. Never mind the bored look on her tanned, round

face as she serves customers at the state-run Restaurante Via Reale

just off the Plaza, writing orders on scraps of paper, or her hand,

and setting down drinks under the direction of a senior server. She

gives away her real motives even as she professes her love for service:

her wild, frizzy blond hair is pulled back to show off aquamarine and

gold plate earrings that match one of several rings adorning her childish

hands. A gold-colored watch, its shine already fading, tells her when

it is time to go home. These are things that in Cuba, only dollars can

buy, and she, like Dany, knows that a job in tourism is the fastest

way to get them.

Chuchy is in her last year

at the Escuela Economia, the secondary school that feeds directly to

the FORMATUR, where she can study for one, two or three years, depending

on how high up she wants to go. To work in one of the peso cafeterias

near the Parque Cespedes in the Cuban part of town, she needs only a

few months of training, but to work with foreign tourists, she'll need

language proficiency. In the meantime, she earns enough tips doing her

internship at Via Reale to keep herself well dressed.

Her husband already works

as a waiter, and his mother works in a gift shop at the Costasur Hotel

on the peninsula. From the outside, the house they all share looks like

any on the dusty block. But inside, it is a veritable temple to all

the things that tourism money buys: a Panansonic 5-CD changer, a new

television and VCR. The family even has a car in the cinderblock garage

behind the house. Their stereo cost $450 in the dollar store. That is

twice as much as it will cost Dany to put a roof on his new house.

In this egalitarian society,

the disparity between people like David and Maria, and Cuchy's family

has not gone unnoticed. Even the Communist Party leaders here readily

admit that dollar tips are creating inequalities and upsetting the wage

structure. But discouraging tipping, as they did in the early 1990s,

was ineffective, and asking workers to hand over their earnings for

redistribution proved unrealistic. Boris Turino, the frumpy but charismatic

Secretary General of the Communist Party at the new Trinidad del Mar

hotel – there are party representatives in every hotel in Cuba

– has begun to think that tips are a good thing. "If I ask

a waiter, did you get a tip, and he says no, I know that he did not

give good service," Turino says. And since Cuba's five tourism

companies compete against each other for revenues, good service feeds

the bottom line.

|

His

pressed, sky blue collared shirt is open just enough to show off

the flat, round, silver pendant, his initials scripted across

it, that hangs on a modest silver chain against his hairless chest.

Crisp

khaki shorts have replaced his dirty red ones, and as he strides

out into the street, his new Adidas reflect the moonlight.

All,

he explains, are gifts from tourists.

|

So instead of fighting the

realities of the tourism industry, the government began boosting other

sectors in 1999, including a 30 percent increase in public health and

education salaries and productivity bonuses distributed as magnetically

striped cards that can be used in dollar stores. In some industries,

like fishing, where the incentives for cheating are high, salaries are

now paid partially in dollars.

"In the Special Period,

when there was no money, and when the economy was down, that's when

there was a move of professionals trying to get into tourism,"

says Turino. "Now things are stabilizing."

Sitting in front of his

ancient, Soviet style television with its faux wood siding and milk-bottle-bottom-thick

screen, Dany isn't so sure about that. The beans and rice dinner he

ate for what seems like the millionth night in a row has left its usual

hole in his stomach. He isn't willing to trust that a beefed up government

salary will keep meat on his table. If he wants the real goods, he has

to rely on hard currency -- dollars.

When he steps out the door,

hollering good night to his father over the still babbling radio, Dany

is a changed man. His pressed, sky blue collared shirt is open just

enough to show off the flat, round, silver pendant, his initials scripted

across it, that hangs on a modest silver chain against his hairless

chest. Crisp khaki shorts have replaced his dirty red ones, and as he

strides out into the street, his new Adidas reflect the moonlight. All,

he explains, are gifts from tourists.

"I never buy my own

clothes," he brags, shaking the too-big "titanium" watch

that hangs loosely from his dark wrist. The only clothes he could afford

anyway are the ones in the peso stores, most of them donations from

Spanish or even American church and humanitarian groups. "Nobody

likes the stuff the state sells. Everybody prefers el shoping"

he says, referring to the dollar stores. What he doesn't get free from

tourists, he buys on the black market. That's where he got the watch

and the four silver rings that clutter his hands. The cologne he wears,

though, must have come from Trinidad, since the same scent permeates

every street corner and stoop where young Cuban men gather.

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

Heading toward the plaza,

Dany thinks back to the Italians and their dinner, and wonders aloud

if they will be going to the Casa de la Musica tonight, one of five

state-run clubs tucked into the neighborhoods around the Plaza. If he

finds them, they might pay his $1 entrance fee. Or maybe the French

guys he talked politics with the evening before will. Anyone, really,

as long as its not out of his own pocket. "Last night I had seventy

pesos," he explains. "Three dollars, more or less. I could

have gotten into the Casa de la Musica, but I couldn't have bought anything

to drink. With pesos, we can't even go out in our own country."

The nightlife here isn't

really intended for the Cubans anyway. Dany can hear the music spill

out of the open courtyards all around town, filling the still-warm moist

Caribbean air with a riot of afrocuban beats and the cheerful rhythms

of Son, Cuba's folk music. The medley is the same every night. Songs

from the Buena Vista Social Club are played again and again, in club

after club, to make sure the tourists get the Cuba they expect. Even

local music is a state enterprise, packaged and sold for dollars.

Some clubs are worse than

others. Dany almost never goes to Las Ruinas de Sagarto, just around

the corner from the Casa de la Musica. There, 20-year-old Daniel, dressed

in african-print pants and a baggy green shirt, his Chicago Bulls hat

left behind on a corner table, begins the night's show by raising his

powerful, pitch-perfect voice over a pulsing drum beat. He has been

singing since he was seven, when his father and uncles began teaching

him the music and languages of Santeria, the afrocuban religion that

was one of the few tolerated by the revolution. He plays everything

-- the timbales, the guiro, the claves.

At Las Ruinas, Daniel accompanies

himself with the gurino, a huge, hand-made beaded gourd that showers

pellets of sound into the microphone. A thicket of wires connect a beat-up

amplifier to an old tape player that records performances, night after

night, onto tapes sold later for a little extra profit. Three men seated

behind the timbales join in with a deep, insistent, rhythm that propels

a motley group of costumed dancers who act out the work of the slaves

who toiled in the sugar plantations here until they were freed in 1886.

From their midst, a handsome woman in purple silk emerges, straight-backed

and haughty. Waving a hand broom impatiently, face impassive, she shoves

a straw hat towards a German man sitting in the front row. He's seen

this before and reluctantly pulls his wallet out again. She moves on.

"It is all for the

saints," Daniel says after the show. But it is clearly for the

tourists' money, too. At the end of the night, when everyone else has

gone home, the dancers and the players divvy up the tips, dollar by

blessed dollar. Each of the players and dancers in Daniel's group also

earns a small government salary. Like everything else here, there is

a set process for becoming a musician and performing for the tourists

– schools, tests, provincial auditions -- that controls who plays

what and where.

Dany's friend Manuel is

one of the luckier musicians. His band has built up an international

reputation, so for him playing music means travel opportunities that

most Cubans will never have. Half of his group is in Mexico performing

now, and although he was not allowed to go this time, he expects to

go next month. He will even get to keep some of the profits they make.

All it takes, Manuel claims, is an invitation from abroad. While he

waits, he sells cigars on the street. It is easy to see, from his Rolex

watch and brand name clothes, that he's good at that too.

| "I

want to live in Cuba forever," Dany says passionately, tapping

his hand to his heart the way people do here when they talk about

their country. "But with money." |

In the end it is me that

gets Dany into the Casa de la Musica, an old red brick courtyard with

arched passageways and a lit-up stage on the back side of the escalera.

A stern policeman is standing near the door when they arrive, his conservative

green uniform almost comical next to the skimpy spandex dresses the

Cuban women wear. He is probably just doing his rounds, but Dany won't

take the chance of walking in with his new friend. Cubans accompanying

tourists are automatically suspect, and he doesn't feel like being hassled.

So instead, barely hiding his embarrassment, he takes my dollar outside

and walks in ahead of me, looking around for his friends and an empty

table. He spots Manuel, already talking to some foreign girls. The Italians

are here, too. Dany slaps the man five, puts his arm around him, and

before long, the man hands him $4 for a bottle of Havana Club Silver

Dry rum. That's $3 less than the Italians would have been charged. Passed

around the table with a can of coke, the bottle lasts as long as the

music does.

Dany and his friends are

not the only locals at the club. It is one of the few places in town

that has dancing, and that is what the Cubans come for. The courtyard

is full of sexy young men and women, dressed for flirting. When the

salsa rhythms start, the dance floor fills up with bodies moving fluidly

together, swinging in time to the rattling maracas and singing guitars.

The irresistible motion and insistent invitations soon lure the tourists

up from their seats. They are conspicuous in their clumsy steps and

the sporty shorts and sneakers they spent the hot day in.

The end of the night, when

the band reels in the wires and the stage clears, is when the real fun

begins. The pumping bass of Cuban rap comes blaring through the loudspeaker

and suddenly everyone is up, stomping and thumping and rapping along.

It is mostly young people left now, and even the visitors know what

to do. This is what Dany has been waiting for. This is Cuban time.

Later, walking home, Dany

passes a group of young Cuban women, tube tops hugging as tightly as

their spandex skirts, with an entourage of tall pale-skinned foreigners.

"One, two, three," he counts out loud, taunting. "four,

five. Five girls for four guys?" he asks. "Two for one. I

guess that is the Cuban way." There is a fine line here, between

a good time with a Cuban girl and outright prostitution. Dany wouldn't

think of pimping women – "straight to prison," he explains

-- but there is nothing to stop women from accepting a few drinks, maybe

a new dress, from a tourist, and going home with him for a few more

dollars. I overheard a couple of men complain, though, that like everything

else here, the women aren't as cheap as they were a few years ago.

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

Tourism has been called

the locomotive of Cuba's economy. And indeed, it is the driving force

behind internal development, and the primary source of hard currency

to service the country's $22 billion external debt. But even as it relieves

financial pressure, tourism and the dollar economy it has spawned are

redefining Cuba's priorities. People who once gave the proverbial middle

finger to their powerful northern neighbor are now increasingly dependent

on its currency. Highly educated engineers, doctors and teachers are

giving up their careers to drive taxis and scrub hotel bathrooms. The

tenet of income equality that underpins socialism itself is being allowed

to disintegrate in the name of economic growth. And everything Cuban

is now up for sale – music, art, even women. Like any export-based

economy, the good stuff is appropriated for the foreigners.

But those same dollars that

are driving women to prostitution and the elderly to begging are saving

ordinary Cubans from reliance on a government that can no longer feed

them. Dany is angry that he needs dollars, and yet desperate to get

more. It disgusts him to see the women he went to school with cozy up

to tourists, but even he relies on a tourist to buy him a drink or pay

his way to a club.

Dany doesn't ask for much:

a house big enough for him and his father to live comfortably; a bus

ticket to Havana to visit his sister, so he doesn't have to hitchhike

for an entire day to get there. But to get these things, he has to have

dollars.

"I want to live in

Cuba forever," Dany says passionately, tapping his hand to his

heart the way people do here when they talk about their country. "But

with money."

He fingers the pendant at

his neck and wrinkles his dark forehead as he looks out over the Plaza

Mayor. On nights when he is sad, he comes here to watch the stars, taking

over one of the benches that during the day belong to the tourists.

From here, he can listen as the music dies down and the bars slowly

empty out, as the hushed voices of couples dissolve into the darkness,

as the footsteps of the foreigners fade away. At last, when the quiet

settles in, the town belongs to him again. And from where he sits, it

is easy to understand why he stays. "With enough money," he

says, "Cuba is everything."

Back

to stories page