Four Women

By

Alicia Roca

Researcher: Nichole Griswold

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

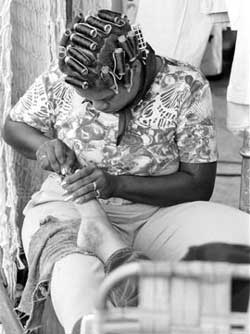

Every

month Cubans are entitled to food rations. The elderly, pregnant

women and children under the age of eight also receive two liters

of milk a month.

|

It's six. Rosa

fumbles with the light switch, roosters crow somewhere in the darkness.

She pulls a chair by its back and climbs on it. She jiggles the light

bulb; a little to the left, then to the right. At last, it hums, flickers

and emits a dim orange glow.

"Hay que

inventar." You have to invent, she says with a slight smile.

It is a phrase

often used in Manzanillo, a parched, sweltering city of about 100,000

in Cuba's poorest province, Granma.

"No es

facil." It's not easy.

Rosa explains

that since the collapse of the Soviet Union a decade ago, everything

is in short supply, particularly light bulbs. Those available cost $4,

one-third the average Cuban's monthly salary. For Rosa, a 78 year-old

widow who does not receive money from Miami relatives, light bulbs are

a luxury. So are toilet paper (for which she substitutes newspaper),

toothpaste, deodorant, and shampoo.

The first thing

Rosa does every morning is clean. She wraps a damp cotton rag around

a wooden stick and drags it across the concrete floor. Her back is hunched

causing her spine to protrude. Her thin arms sweep slowly back and forth.

"I can't

live in a dirty house. My husband always wanted a clean house."

But chores

weren't always a priority. In 1956, Manzanillo was alive with revolution.

Late that year the Granma, a boat carrying Fidel Castro and 82 men from

Mexico landed 60 miles from Manzanillo. Waiting for them was Celia Sanchez,

the daughter of a provincial doctor, and the woman who organized the

underground network, based in Manzanillo, that would support them for

the next two years. For months, Sanchez moved from house to house depending

on the residents on Manzanillo to evade Fulgencio Batista's men. In

exchange for the promise of a better future, the locals fed, housed

and shielded her from government inquiries. With their support, Sanchez

funneled guns, supplies, soldiers, nurses and even reporters such as

Herbert Matthews of The New York Times to rebels in the nearby Sierras.

Rosa remembers when Sanchez stayed in a house across the street from

her. And she remembers the other women who became models for the modern

Cuban woman.

Haydee Santamaria

and Melba Hernandez were nurses in the attack on the Moncada barracks

in nearby Santiago. The Mariana Grajales, an all-woman platoon, fought

alongside men. Violeta Casel was the first female announcer on Radio

Rebelde. Some, including Lidia Doce and Clodomira Acosta, Manzanilleras

and mountain messengers, became martyrs after being tortured to death

by Batista's men. The Giralt sisters, members of the underground, were

gunned down at their apartment. Countless others, now forgotten, exploited

stereotypes of women as naïve and incompetent when working as gunrunners

or smuggling subversive pamphlets beneath their skirts.

| "My

mother always told me a woman has to look her best." |

Manzanillo

was their base and if peasants here suffered most during Batista's reign,

they gained most in the early years of the revolution. The province

was renamed for the boat, the Granma, that landed in 1956. A hospital

that bears Celia Sanchez's name went up, schools opened and doctors

arrived, but 45 years later, the revolution and its gains seem like

ancient history. Manzanilleras are at the bottom of Cuba's reemerging

dollar-based social strata. Gone are the fervent guerilla warriors and

in their place are everyday women with everyday struggles. Like making

a lightbulb come to life.

After Rosa

cleans, she starts breakfast. The process takes an hour although she

is making coffee and toasting bread. She drips liquid fuel into a spoon.

Her hand shakes. She tips the fluid into a small bowl. She turns the

iron burner on and places the bowl beneath it. She lights a match. Nothing.

"Le hechan

mucha agua al combustible." The fuel is too watered down.

She smiles

and tries again. It takes her fifteen minutes. The smell of gas is thick,

making it difficult to breathe in the cramped kitchen, but Rosa won't

open a window. She's afraid. A year ago a young boy broke in and stole

Rosa's towels and iron.

"They

weren't even towels. They were more like rags."

She still doesn't

have any towels, and her only iron must be heated over an open flame.

She irons her clothes every morning.

"My mother

always told me a woman has to look her best."

Since the burglary,

Rosa stays locked indoors. She always isolated herself, neighbors say,

but now she only leaves to buy food and see doctors.

| This

is Rosa's litany: people had morals then. Today, the young don't

want to work. They look for easy ways to make money. They are sexually

promiscuous. They are struggling because they do not try to better

their lives.

|

When she was

young, life was different. This is Rosa's litany: people had morals

then. Today, the young don't want to work. They look for easy ways to

make money. They are sexually promiscuous. They are struggling because

they do not try to better their lives.

Before the

revolution, poverty and illiteracy were rampant in the countryside.

Over half the population couldn't read. Women turned to prostitution

to survive. Today there are other options, Rosa says. Education is available

to everyone. How far they go with school depends on how hard they are

willing to work.

Rosa lugs water

in pails from metal barrels so she can bathe. The task is difficult

for Rosa who suffers from arthritis, cataracts, and weighs eighty pounds.

As she flips the bathroom light switch, cockroaches scatter. They are

the size of small rodents, with wings.

Today the milk

arrives and Rosa is happy. She loves milk. She would drink it three

times a day if she could.

Every month

Rosa and other Cubans are entitled to four rolls of bread, one pound

of salt, four cans of fish, five pounds of rice, six pounds of sugar,

ten ounces of beans, one pound of coffee and ten eggs. All this food

can be purchased for about four pesos, or twenty cents and it adds up

to 298 calories a day.

The elderly,

pregnant women, and children under age seven also receive two liters

of milk a month. But complications arise. Sometimes not all items are

available; people tend to run out of food toward the end of the month.

Additional food must be bought at higher prices, so the poor, like Rosa,

stretch their rations by having one meal a day instead of three.

After bathing,

Rosa finishes the coffee. She dips a teaspoon into a jar filled with

sugar and swarming with ants. She pours the milk through a strainer

and splits the curd between her dog and cat. The dog takes the cat's

share. The cat meows and scratches Rosa's leg.

Rosa mixes

the milk, coffee and sugar with a small metal spoon.

"A morning

without coffee is like a dark, dark night," she says.

There is a

knock at the door. She cocks her head.

"Voy."

I'm on my way, Rosa yells.

She hooks a

chain on the door, opens it a crack and peers out with one eye. In a

sliver of light, a boy, about five-years-old, holds a golden peso in

his hand. He reaches into the darkness and lays the coin in her palm.

"Who are

these for?" asks Rosa.

"For my

Mom."

"How many

does she want?"

"Two,"

he says

| "I'm

poor. I don't have much, but everything I have is yours." |

Rosa takes

a clay bowl from her cabinet, drops the coin in it, and removes change.

She slides a tattered brown box across the table, pulls its lid off

and lifts out two cigarettes. She gives the boy the cigarettes, the

change, and shuts the door.

All Cubans over the age of forty-four are entitled to two boxes of cigarettes.

They pay four pesos per box. Like Rosa, many sell their cigarettes to

buy other goods.

Rosa puts the

money bowl on the cabinet shelf and dribbles oil into a pan without

a handle. She rotates the pan with pliers. She places her breakfast,

a white roll, in the pan and browns it.

She opens the

cabinet and cradles a beige, intricately crocheted tablecloth. When

her husband was alive, Rosa spent much of her time crocheting. Though

she was college-educated, he forbade her to work or leave the house

without him. They never had children. Prior to marrying him and prior

to the revolution, Rosa worked as a tutor for wealthy children.

Rosa unfolds

the tablecloth, shakes it and drapes it over the kitchen table.

"I'm poor.

I don't have much, but everything I have is yours."

When her husband,

Juan, was alive, life was better. She never wanted for anything. She

calls those the happy days and divides her life into two periods- when

Juan was alive and now. Juan died ten years ago, at the same time the

island lost Soviet aid.

Relatives try

to persuade Rosa to move to Habana or Santiago where conditions are

better, but she won't. She won't even visit. There are too many memories

in her house.

As she sets

out to buy milk, Rosa stands before the bedroom mirror and brushes back

strands of hair with her fingers. Missing clumps reveal pink skin several

shades lighter than her caramel complexion. Rosa wraps a scarf around

her head to hide it.

She flicks

the window locks. She jams a chair up against the back door and locks

the front door.

"Quedate

aqui. Cuida la casa." Stay here and guard the house. Sandito, the

dog, barks and wags his tail.

She slams the

door shut and greets a neighbor.

"How are

you?" he asks.

"En la

luchita." In the little struggle, she says with a smile.

|

|

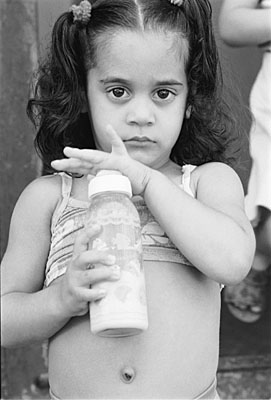

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

As Rosa wakes,

Felicia arrives at school.

Her class doesn't

start until seven but the bus comes at 5:30 a.m. It's too far to walk

and the horses-drawn carriages, the primary mode of transportation in

Manzanillo, aren't out that early. Sometimes Jorge, Felicia's husband,

takes her to school on the back of his bicycle, but Felicia prefers

he stay home and attend to her son, Jose. Children stop receiving milk

at seven and Jose is nearly eight. It is a struggle to find breakfast

for him. Yesterday all he had was a piece of bread with cooking oil

on it.

"But there

are people in worse situations. Most of the kids in my class come to

school on an empty stomach. How can they think with an empty stomach?"

asks Felicia.

A few days

ago Felicia gave one of her students a peso for a haircut.

"Some

of these parents just don't care."

Felicia lives

near the ocean in a neighborhood called El Malecon. Her school is in

the hills, in one of Manzanillo's poorest barrios.

Felicia waits

in the teacher's lounge for school to begin. She is a secondary school

English teacher. Secondary school includes seventh through ninth grade.

Schooling through ninth grade is mandatory. After that, children with

the best grades go to the pre-university level where there are general

schools and scientific schools. Others go to military schools, art schools

and technical or trade schools. Few of Felicia's students will go on

to the pre-university level. Masters and doctorates are available by

invitation only.

At seven, students

file into the classroom. The other teacher is absent, so Felicia has

eighty students instead of forty. She turns on a small color television.

It is time for tele-class, a new one-hour live broadcast from Habana.

The government developed it five months ago in response to the teacher

shortage. The same tele-class is shown to seventh, eighth and ninth

graders.

The rowdy children

settle down when the television teacher begins speaking. He greets them.

His name flashes on the screen. For the next hour he speaks in English.

He asks the children to repeat after him, to respond in English, to

copy sentences. But they don't understand any of it and talk among themselves

instead. Felicia paces the aisle shushing the children, warning them

to listen. Several students walk in late. All the seats are taken so

they sit on the floor or stand. Some can't see the television.

"I didn't

know you lived so far from school," Felicia says to one latecomer.

A bell rings

signaling the end of class. The children jump out of their chairs. They

had no chance to ask questions, nor did Felicia have a chance to teach.

Prior to tele-classes Felicia wrote lesson plans, led discussions, and

assigned homework. Now she maintains order. Some suggest taping tele-classes

enabling teachers to pause them for questions, but there aren't enough

videotapes.

|

Most

people go home for lunch, but she lives too far away.

"Six

years without lunch. I am so hungry," she says.

|

At 8 a.m. Felicia

walks to the teacher's lounge and waits. She only teaches one class

today, but stays in case she is needed. She is paid 300 pesos a month,

roughly $15.

At noon she

strolls around the corner to buy a snack. She stops at a small concrete

house with children in front. One little girl has a Barbie Doll. The

others chase after her.

"Dejame

ver la muneca." Let me see the doll, says a thin, curly-haired

girl in a red T-shirt.

A sign on the

door lists today's specials: Pru, a root drink, Fritura, a fried corn

patty, and pizza. She settles on the pizza and a sugary pink drink similar

to Kool-Aid. The pizza costs two pesos. It is a small thick bread with

tomato sauce and crumbled cheese. In three bites it's gone. Most people

go home for lunch, but she lives too far away.

"Six years

without lunch. I am so hungry," she says.

It will be

another six hours before Felicia eats dinner. Her breakfast of coffee

didn't stop the hunger pangs, nor did the tiny pizza. But she would

rather she go hungry than her son or husband. She often goes without

to provide for them. One time she went a year and half without shoes.

Today, she nearly forgets it's her birthday.

"I'm celebrating

by cooking and cleaning," she says when she remembers she's now

33.

Eight years

before Felicia's birth, women revolutionaries founded The Federation

of Cuban Women (FMC). The goal was to eradicate machismo and create

a more equal society. They fought for eighteen weeks of paid maternity

leave, free contraception, pre-natal care, abortions, and a national

daycare system for working mothers. But equality is still a distant

goal. Women, especially Manzanilleras, bear a disproportionate burden.

Felicia prefers

not to discuss politics.

"My politics

are my son and my husband, my family."

While her father

is not in her life, Felicia has a close bond with her mother, who raised

her.

|

Today,

she nearly forgets it's her birthday.

"I'm

celebrating by cooking and cleaning," she says when she remembers

she's now 33.

|

It is time

for an assembly. The teachers in the lounge trudge to the schoolyard.

A doctor stands at a podium yelling because there is no microphone.

She's hard to hear and the children talk among themselves. It is nearly

one hundred degrees and there isn't a breeze. The sun is merciless.

"Escuchen.

Es importante." Listen, it is important, says the doctor.

The doctor

alerts the children to the dangers of viral meningitis. She describes

the appearance of the mosquito that carries it, and symptoms. Fumigations

are occurring across the countryside, she tells the children. Only a

few people have as yet contracted the illness, but it hasn't been seen

in Cuba for decades, and health officials fear an epidemic. They suspect

a mosquito carried it across the Atlantic on a cargo ship from Africa.

"Can we

count on your help?"

"Yes,"

the children shout back.

Felicia leads

the children upstairs then returns to the teachers' lounge. She makes

small talk to pass the time. She opens a worn brown book and points

at a United States map. She smiles.

"Where

is Michigan?" She has a friend in Michigan. It would be nice to

visit, she says.

At five Felicia

heads home. It's a fifteen minute walk downhill to the horse and carriage

stop. She hails the first one.

"Hay lugar,

cochero?" Any room, she asks.

But all are

full. Another fifteen minutes pass. At last, one with room. The cochero

stops and Felicia climbs on.

"This

is a Cuban taxi," she says with a smile.

She points

at a passing horse and carriage.

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

Cuban women

struggle to make ends meet.

|

"Would

you believe me if I told you that man was once the best history teacher

in Manzanillo? He quit and now makes more money as a cochero."

Has Felicia

ever contemplated quitting her job? Perhaps for a more lucrative one

in the tourist sector?

"No, I

love my kids," she says. "I'm

a teacher."

Her best friend

Angel works at a tourist resort nearly three-hundred miles away in Cienfuegos.

He has friends from abroad who visit and leave generous tips when they

check out. When Angel visits he will hide a five or ten dollar bill

somewhere in her house. Sometimes she'll find one in a pair of pants

or under a dish. It's her only access to dollars.

"He knows

I won't accept it if he hands it to me. We're all struggling and he

can't afford charity anymore than I can. But by the time I find it,

he's already gone."

After a twenty

minute ride Felicia pays the cochero one peso and begins the long walk

home. When she arrives, Kevin, the dog, is whimpering. He's tied up

and hungry. If she were to untie him, he would run outside and be stolen.

She puts leftover rice and beans in a tin plate. Kevin wags his tail

and devours the food.

Felicia's mother

and Jose are waiting too. Jose's elated face is smeared with dirt. She

hugs him and tells him to clean up. She prepares a bucket of water and

finds a bar of soap.

While Jose

washes in the backyard, she carries a bucket of water to the outhouse

and pours it into the toilet to flush it.

She changes

into shorts and a tank top and walks to the kitchen. She points to the

kitchen ceiling. There are several lose bricks.

"Watch

out. They could part your skull."

The kitchen

is filled with chicken wire, bags of concrete and scraps of wood.

| It was

Jorge who rode his bike up into the mountains in search of firewood

when there was no combustible liquid to light the burners. It was

Jorge who found platano trees when there was no food. |

Jorge is planning

to fix the house. They bought it for a good price because there are

holes in the walls and ceiling. Mother, father and child share a small

room with a bed, a crib, and an armoire. Jose sleeps in the crib. They

cannot afford a bed for him. Even if they could, there's no room for

one.

Felicia is

proud they have a home of their own.

"We own

this, we don't rent," she says.

Felicia's first

marriage was to Salo, a man she met in college. They were happy for

a while, but after Jose was born, he began to change. He became distant

and withdrawn. He dropped out of school. Then he disappeared only to

resurface in jail. He had built a raft and attempted to reach the Dominican

Republic. Instead, he washed up on Cuba's southern shore. He spent four

years in jail for attempting to leave.

"He said

'If even a dove, an animal, migrates in search of better conditions,

shouldn't we humans?" After that she divorced him. She was hurt

that he had not discussed his decision with her. She was even more hurt

that he would abandon their son. It was then that she began dating Jorge,

a childhood sweetheart.

"If it

weren't for him, Jose and I would have starved during the Special Period,"

says Felicia, referring to the early 1990s when food was even scarcer.

It was Jorge

who rode his bike up into the mountains in search of firewood when there

was no combustible liquid to light the burners. It was Jorge who found

platano trees when there was no food.

"You ate

whatever you could because you never knew when you'd have your next

meal."

Felicia makes

dinner. She pours rice onto a piece of cloth. She sits at the table

to clean the rice.

She lifts the

tablecloth to reveal a table made of wood scraps. Rusted nails jut from

it.

"Jorge

made it."

She continues

picking out bugs, rocks, dirt and discolored grains of rice.

It takes fifteen

minutes before she pours the rice in a bowl, lugs water in from out

back, and washes the grains. Next, she cleans the beans and lights the

burners.

Jose runs clutching

a piece of pink paper. He prances around the kitchen, waving it in the

air.

"Look

what I found today, Mami. Colored paper!"

Ana starts

work at seven. Her job is a forty-minute walk from her home. Her boyfriend

usually takes her on the back of his bicycle, but not this morning.

Today reminded

her of the days when prepared breakfast for the two older children,

sent them to school and then went to work with her youngest child in

her arms. That was thirty years ago when her husband left her for another

woman. She was twenty-four then and raised her children without any

assistance.

Single mothers

are more common nowadays. Between 1973 and 1988, 39 percent of all Cuban

children were born to single mothers, by 1989, 61 percent.

"No era

facil. But we survived."

| Ana

and another cook are in the kitchen. It's a small room without windows.

No one else is allowed in because years ago, someone put crushed

glass in the children's food. |

For the past

three decades Ana has been a cook at the Circulo Infantile, a government-run

day care center. The program provides low-cost daycare for working mothers

at 20 to 70 pesos a month depending on the parent's salary and the number

of children in the family. Initially, the program was free but it became

too expensive for the government.

The children

are between 6 months and 6 years-old. They begin arriving at 6 a.m.

and are picked up by 7 p.m. Ana's responsible for preparing their morning

snack and lunch. At 9 a.m. children have milk or orange juice, if available.

Today the children had a yogurt drink and bread.

Ana would like

to retire, but she needs the money. In Cuba, women can retire at 55,

men at 60.

Ana and another

cook are in the kitchen. It's a small room without windows. No one else

is allowed in because years ago, someone put crushed glass in the children's

food.

"Te imaginas?"

Can you imagine? asks Ana.

|

|

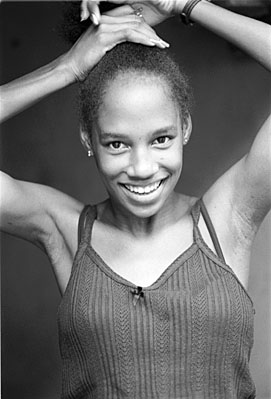

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

Outside, the

children are divided into groups. All the workers are women. Each one

has a group of ten to fifteen children. They sing songs and play with

the children. One woman, about Ana's age, is in charge of the 3-year-olds.

She sings a song about rabbits. A boy cries as his father leaves. Two

others fight over a red flower. A little girl pulls a little boy by

the ear and he screams. There aren't enough chairs to accommodate latecomers.

"I'm so

tired," says the teacher.

She holds up

laminated pictures glued on popsicle sticks.

"What's

this," she asks.

"A lion,"

says the crying boy.

"Yes,

a lion. And where does the Lion live?" she asks

"In the

zoo."

Across the

yard, 6-year-old boys sit at tables, drawing on scraps of notebook paper.

A pencil breaks and the caretaker sharpens it with a knife. As the boys

draw, the girls play at life-size stations made of cardboard. There

is a factory, a kitchen, a beauty salon, a hospital, and cars. A group

of girls plays in the kitchen. One cooks while the others sit at a table.

The cook serves equal portions to each girl.

"Eat all

your food. It's rice, beans and chicken," she says.

When Ana gets

home at 3 p.m. she makes dinner immediately so she can have the evening

to herself. Her boyfriend comes home at four. Tonight Ana is visiting

a friend, Oda. Oda moved to Habana six months ago. This is her first

time back. Oda is homesick and unhappy about the move. She wants to

return to Manzanillo because her family is here. In Habana she is isolated,

depressed, and losing weight. A robust Manzanillera is considered beautiful.

When her friends call her "flaca", thin, it is not a compliment.

They say it with concern. They pinch the pink spandex of her dress to

show how loosely it fits her.

"Tienes

que comer, Oda." You have to eat, says her worried sister.

Ana carries

a Batido de Trigo, a wheat smoothie to Oda.

Though Oda

loves her husband, she is considering leaving him to come back. Like

many women in Manzanillo, her family is her priority. She feels uprooted

in Habana, though conditions are better.

"Have

faith in God. It will pass," says Ana.

She is a devout

Baptist as is Oda.

"Ponte

de rodilla y ruegale al Señor." Get on your knees and beg

the Lord for strength.

"It isn't

easy," replies Oda.

| A robust

Manzanillera is considered beautiful. When her friends call her

"flaca", thin, it is not a compliment. They say it with

concern. They pinch the pink spandex of her dress to show how loosely

it fits her. |

Oda's sister,

Flora needs advice too. For the twenty years of their marriage Flora

tolerated her husband's affairs. He was recently arrested and Flora

went to visit him. Another woman was there.

"Votalo

ya." Dump him, advises Ana.

"There's

a point where you have to say 'no more' and love yourself more than

you love him. You can't live like this."

Ana knows about

cheating men. She complains that Cuban men are mujerieros, womanizers.

"They

don't want to stay with one woman," she complains.

After Ana's

husband left her, she met another man. She fell in love and they were

together for several years.

"But he

was too good-looking." Women chased after him.

"The women

here, they don't care if a man is with someone."

So Ana left

him. He is a tall, handsome man with a black mustache. Even now, when

they meet on the street, she hardly resists his charms.

"He wants

to be with me, but who can be with a man like that?"

After that

relationship Ana met another man. She was with him for eight years but

he followed another woman to Habana. Later he returned, ill and disheveled.

Ana nursed him to health.

"I guess

I was better." Ana smiles.

They have been

together five years since then. He lives with Ana.

"But it's

my house. I own it." Ana's eyes sparkle. The pride in her voice

rivals the tone with which she speaks of her children.

"It's

not much, but it's mine."

|

|

photo

by Mimi Chakarova

|

As Ana arrives

home, Belen is cleaning. She wets a gray rag and wipes it across the

counter. It's 9 p.m. and she just walked in the door. She too had a

long day. She leaves for work at 7 a.m. and it's a forty-five minute

walk, but she likes the time alone.

"Give

me hot chocolate now," demands her 9-year-old brother.

She ignores

him and pulls a strand of black hair behind her ear. She swats away

flies with her hands. Her cheeks are flushed.

"Nowww"

he whines.

She rolls her

eyes, sighs and lifts the milk off the cupboard shelf. They have to

drink it as quickly as possible. They don't have a refrigerator.

When her mother

isn't home, Belen is the matriarch. As if on cue, the 5-year-old twins,

run in. They are clad in underwear. Their petite facial features are

perfectly chiseled, as if from marble, and their wavy black hair in

a disarray. One twin is screeching, the other laughing.

"Nina

me jalo el pelo," Nina pulled my hair, says one, eyes wide with

astonishment.

The other continues

laughing and runs out the back door.

In the living

room, Belen's grandfather and his trio make music. Two of the men are

middle-aged. They arrive immediately after work every day and stay for

hours. Belen's seventy-year-old abuelo is the oldest and most experienced

musician. He founded the trio half a century ago. Belen grew up with

the sounds of his guitar, as did her mother.

The three men

fill the house with traditional Cuban love songs, boleros. They sing

of loves lost, unparalleled devotion and beautiful women.

"O mi

amor, por siempre tu." O my love, for always it will be you, her

grandfather croons.

"Are you

hungry?" Belen yells. With one hand on her hip, she wipes the sweat

from her forehead.

He stops singing.

"Of course

I'm hungry. When's dinner going to be ready?" he asks. There is

irritation in his voice.

Belen prepares

the rice. Melodies arise in the background.

"They

say it's women's work," she whispers.

| Divorce

is common. Many Cubanas have been married multiple times. Couples

can divorce easily if their marriage "loses meaning" or

if a spouse is "abandoned" for six months. |

Belen's ex-husband,

Luis, had the same idea. She thought he was romantic at first. He seemed

protective, not controlling. She drew other conclusions when she found

he was cheating.

"Tenia

otra mujer." He had another woman, says Belen.

Belen and Luis

only knew each other for a month before they were married. She was flattered

that a man ten years older was interested in her; especially a good-looking

man. It was a way to get out of the house, and start a life of her own.

But the marriage only lasted 9 months. Why did they marry so quickly?

"Because

he wanted to," she says. She doesn't want to discuss him anymore.

Divorce is

common. Many Cubanas have been married multiple times. Couples can divorce

easily if their marriage "loses meaning" or if a spouse is

"abandoned" for six months. In addition, boys as young as

16 and girls as young as 14 can legally marry.

By 1987, more

than one-third of marriages and divorces occurred among adolescents.

In 1992, a majority of married couples were under thirty. Such marriages

lasted on average less than two years.

Belen's ex-husband

still pursues her. He loiters outside her work. He offers to walk her

home. He brings her gifts. She tells him, "I don't want anything

to do with you."

Just a few

months have passed since their divorce, and she is eager to wed again.

"Do you

want to see my wedding album? The gown is beautiful."

She is looking

for a boyfriend, but prospects are slim. She doesn't have time to look

for a man, and there aren't any at school. She yearns to be a mother

and wishes she had children. She smiles at the thought. She would have

some already if her ex-husband weren't sterile.

Her gaze shifts.

An cat jumps over the fence. It is emaciated and severely burned. Most

of its black fur is missing and its pink skin is covered with pus, open

wounds and blisters.

"It was

caught stealing."

The cat went

into a house through an open window or door looking for food. Someone

then threw hot water or oil on it.

"It was

probably a piece of meat or fish."

| When

her mother isn't home, Belen is the matriarch. |

Nowadays, Belen

works at Manzanillo's only medical school where she is a waitress at

the dormitory cafeteria. There are many extranjeros, foreigners, but

tips are rare. For the past 3 years Belen has also been a student at

the school of gastronomy, a trade school for restaurant and hotel workers.

She's learned basic English and service skills. She's learned how to

set a table and how to take an order.

When she was

14, Belen had the opportunity to go to pre-university. Her grades were

high, and teachers encouraged her to pursue college. The pre-universities

are located far away in the mountains where students spend half the

day studying and half the day working in fields to develop respect for

the land and laborers.

After several

months at school Belen returned because she was homesick. Others say

she missed a boyfriend. That was when she chose to attend a gastronomy

trade school.

"Me gusta."

I like it, she says.

Where will

she be in 10 years?

She laughs.

"I don't

know. I haven't thought much about the future."

She would like

to work in a place with more tourists, but that is competitive. And

the idea of leaving home for Habana scares her. She looks down and separates

the discolored grains of rice.

"I'm not

going anywhere," she says.

Back

to stories page