Caught in the cross fire: Is Beirut Ready for Tourism?

Marriage: Lebanese Style

Meet Lebanon's only Male Belly Dancer

Beirut Blues

The Woman Behind the Walls

A Visit to a Palestinian Camp

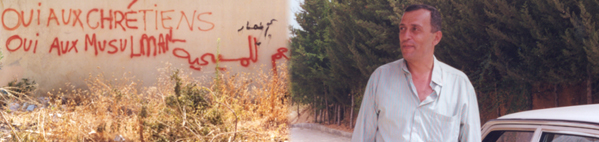

"There is no point looking behind or complaining," he said. Carefully banking the next turn in his old white Mercedes sedan, he admitted that he still feels resentful towards his old neighbors. "They killed my grandmother and it is hard to forget," he said. Said Jakhar is part of an ever-shrinking Christian minority in Lebanon that is trying to carve out a place for itself in a land it once ruled.

Recognized by Rome as Catholics, the Maronites, enjoyed political and economic dominance for decades after Lebanon's independence from French colonial rule in 1943, but the 20-year civil war and a growing Muslim population changed the political and demographic landscape. While the Christians, according to the last and obsolete official 1932 census, used to account for just over half of the population and more than half of the power in the government, it is generally acknowledged --despite the lack of statistics-- that they now comprise only about 30 percent of the population, versus 65 per cent for the Muslims.

According to the Lebanese constitution the power is still shared between a Christian president, a Sunni prime minister, and a Shiite speaker of the Assembly; but at the end of the war in 1990, the powers of the president were substantially reduced while the power of the National Assembly were increased. Clinging to a hopeless dream of restoring their influence of the past, the Lebanese Christians are trying hard to convince the others than Lebanon without them would not be Lebanon. Their argument is simple. According to Selim Abou, dean of the Jesuit Saint-Joseph University in Beirut, "Without the Christians Lebanon would be Syria or any Arabic country". Because of its rugged landscape made of isolated peaks and valley, Lebanon has historically given refuge to all kind of dissidents groups, allowing Christian sects to coexist with Muslim sects and giving Lebanon its uniqueness in the Arab world. When the Maronites were driven out of Syria during the 10th century by repeated Muslim persecutions, they took refuge in the isolated valleys of Mount Lebanon. They later became the elite, developing close links with the French from whom they sought protection and patronage.

...continue

Back to Home Page