![]()

|

Natural

hairstyles assert identity in post-Apartheid South Africa |

|||||||

|

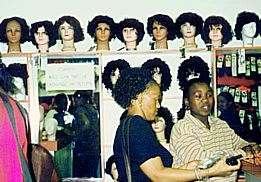

JOHANNESBURG -- Vivian Nurse Mongwe's office is in the middle of Eroloff Street's promenade, one of the busiest pedestrian walkways in the city. She works outside year round and sets up shop between street vendors who hawk ripe fruits and cheap clothing. Mongwe is a street hair braider, skillfully using her hands to meet black South Africa's growing demand for ethnic-inspired beauty. Beauticians around the city speculate that for many black South Africans, the end of Apartheid signaled the end of being ashamed of black culture. With political freedom, has also come the freedom to express external pride in being black. And, at the center of that expression is the business of hair. It's bringing life not only to a beauty conscious people, but also to a largely unskilled black labor force. As South Africa approaches its second multi-party elections in June, the hairstyles of voters standing at the polls will likely look a little more trendy, a little more ethnic, a little more proud to be black. "After 1994 in South Africa, the people began to be proud of themselves because before that we were made to believe in the European style of beauty," said Jabu Stone, one of South Africa's leading authorities on natural hair care. "People started to be themselves and to be proud of who they are and to realize that their culture is what they can sell to the outside world." Stone, who was recently honored by leaders in the Eastern Cape as one of South Africa's leaders of black culture, is widely known for his work with dreadlocks, braids and plaits. He runs a business that makes hair products for natural hair and a school that teaches aspiring beauticians how to work with natural hair. He thinks natural hairstyles best showcase true African beauty and is convinced that the present consumer interest in the hairstyles is more than a passing trend. "Natural styles are here to stay," said Stone who often receives requests to service people who live hours away in the Eastern Cape, Durban, and Cape Town. "I'm not doing anything extraordinary. I'm doing what people used to do. Because of the Apartheid era, people were taught that to be black was a sin. All I'm saying is forget that. Let's go back to who we are." Rose Nkabinde said that her choice to lock her hair had more to do with restoring health to her hair than exhibiting cultural pride or following fashion trends. "It was breaking so I started to just do the locks," said the 25-year-old woman from Natal. "They have been around for a long time. I like them." Lorraine Gaehler, a mixed-raced woman who manages a popular salon in Hillbrow, said since the elections in 1994 the way women look on the streets has changed. "In the past you never used to see black women looking so smart. I know the South Africa black woman as a big fat momma with short hair," said Gaehler. "It's not a thing that has happened over night but they have become beauty conscious." Gaehler's son Lino owns the salon and the pair pride themselves on providing innovative styling techniques and excellent customer service - service which their clients say keeps them coming back for more. "They make sure you are satisfied. Even if it's full of people they will give you better service than other salons," said Jackie Selma a 31-year-old pension fund worker. "They are colored (mixed-race), but they do very good hair." Much like in the United States, black South African women are now finding that beauticians of different races are expanding their services to meet black hair care needs. In one phenomenon, many former white hair salons have been taken over by black owners and clients. Still, it is price, not race or location that determines whom consumers choose to service their hair.Both Stone and Gaehler service their clients in upscale salons, and charge prices ranging from 80 Rand ($13) for a basic perm to 180 Rand ($30) for dreadlocks. Many consumers must stretch their monthly earnings, which are usually around 2000 Rand ($300), to meet other needs and find that street stylists offer the same service as salons at much cheaper prices. "I prefer salons," said Prudence Khumalo, a 22-year-old student who was purchasing hair extensions to have her hair braided. "If you're out there (Eroloff Street) everybody is staring at you." Still, Khumalo's planned to have her hair braided on the street, admitting that street "salons" were cheaper and provided excellent service. Most street stylists specialize only in braiding hair since the absence of water makes doing relaxed styles impossible. Long-time braider Mongwe said prices are so low on Eroloff Street because of the stylists' fierce competition for customers. Each day at least 20 women gather alongside Mongwe. They usually arrange themselves in groups, which Mongwe said are often formed along nationality lines since most street stylists are foreigners who have come to South Africa to find work. To lure passersby, each woman holds a photo album with pictures of hairstyles she is able to braid and asks prospective customers to take a look at what she can do. Mongwe believes she's got the competition beat. Unlike most of the other braiders, she owns her own indoor salon. While two stylists operate the salon in another part of Johannesburg, she braids hair on the streets. Male street barbers are not as aggressive as their female counterparts. They pitch little tents on the sidewalks and hang posters with hairstyles from black hair magazines from the rails of their tents. Many street barbers are foreigners as well. Thirty-three-year-old Kingsley Ashaneso, a native of Nigeria who powers his clippers by running a power cord from his tent into a neighboring church, said cutting hair helps him to survive. "There are no jobs, and the people here they like looking neat. If you want to go to the shops to do your hair it's going to be expensive," said Ashaneso as he gave a customer an English cut, or standard fade. "Here we charge 5 Rand (83 cents), and in the shops they charge 25 Rand ($4)." The former journalist depends upon his clientele to help him pay his rent, 560 Rand ($93) per month, and to save enough money to leave the country. "This place is not very busy," said Ashaneso of his work site. "Sometimes I get 10 Rand ($2) a day, sometimes 100 ($17), sometimes nothing. Everyday cannot be the same. That's just how business goes." Still, for now, hair stylists said the business of doing hair is at an all-time high. Consumers can't agree on why this is so. Some said experimenting with their hair is about getting back to their cultural roots, while others admit they are following fashion. "Some people do it more for fashion. I've done it just to improve my hair," said Busi Peter, a 22-year-old former student who was getting single braids on Eroloff Street. "It grows faster." Prudence Khumalo, whose boyfriend helps her to chose her new extensions from Kinky's Boutique agrees. "It's not a cultural thing," said Khumalo of her new hairstyle. "It's definitely a trend thing." Still for some, wearing braided hair is simply a healthier alternative to wearing relaxed styles. This is true for Yolisa Ndaba, a 20-year-old student from Pretoria who has hundreds of single braids. "I got tired of relaxing, so a girl did it for me in the hostel," said Ndaba. "It's for everybody." What is evident is that the business of styling black hair is booming and that black South Africans now sport locks that celebrate their ethnicity. Shop owners, street stylists and consumers agree that the days of assimilating to Europeans standards of beauty have passed. "Due to Apartheid, I never knew that there were such lovely people in South Africa," said Gaehler. "But black is definitely beautiful. It's a pity they found out so late." |

|

||||||