![]()

|

AIDS:

A multifaceted South African crisis (continued)

|

|||

|

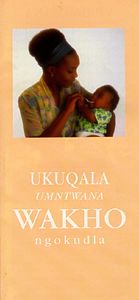

While Similela and the government fight against these larger issues in political backrooms, physicians like the head of Baragwanath's HIV perinatal unit, Glenda Gray are on the front lines. The HIV perinatal unit at Baragwanath hospital is one of five sites in Guateng province where HIV positive pregnant women are being given the drug AZT. This effort is part of the Petra study, a pilot research program aimed at reducing the nation's 30 percent mother to child HIV/AIDS transmission rate. As part of the program, women must also formula feed their babies to reduce the risk of transmitting the virus through their breast milk. Of the 240,000 babies expected to get the HIV virus from their mothers this year, 10 percent will contract the illness through breastfeeding. Beyond South Africa, it is estimated that this form of transmission accounts for 7 percent to 14 percent of HIV/AIDS cases among children. Forcing South African women to give up breastfeeding presents another set of problems. According to Dr. David Woods, Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Capetown and Head of the Neonatal Medical Unit at Groote Schoor hospital, the most common cause of death among South African babies in the first year of life is gastroenteritis -- diarrhea. "The only complete protection against that is breastfeeding," Woods says. In rural communities, where nearly 50 percent of South Africa's HIV/AIDS cases exist, safe running water is a commodity and the cost of formula is exorbitant, especially for women in a country with an unemployment rate of more than 30 percent. Even in Soweto -- a community on the rim of Johannesburg -- families cannot afford to buy formula. Women in rural areas also face the issue of access. Even if they can afford to buy formula, the nearest store might be 10 to 15 kilometers from their homes. Transportation is another limitation for these women because public transportation is almost non-existent and they cannot afford to own their own cars. Asking women to bear this financial burden in a nation where it is not uncommon for children to be breast-fed up until three and four years of age, is almost unthinkable. Little salvation is found in formula donations which present a political hurdle for doctors because of the industry's tumultuous history. Formula companies like Nestle have repeatedly come under fire for promoting artificial infant feeding among African mothers which resulted in a 1977 US boycott of the company. Gray and her staff are not allowed to accept donations of breast milk substitutes. At best, her staff must buy in bulk from a different supplier each month and offer the product at cost to the women participating in the study. Gray's need to find affordable infant formula for her patients has been eclipsed by an even more pressing need. |

|

||