More on Virtual Reality & Storytelling

FEATURED 3D PROJECT: OAKLAND BLUES. Virtual Preservation of Seventh Street’s 1950s Jazz Scene by Yehuda E. Kalay and Paul Grabowicz, Center for New Media, University of California, Berkeley, USA

Keywords: cultural heritage, jazz, West Oakland, California, digital recreation, visualisation, interaction, 3DStudioMax.

Abstract

The seemingly limitless applications of digital technologies make them an ideal vehicle for the recreation and dissemination of cultural heritage. Digital media can be used to recreate cultural content through modelling buildings, people, and their activities; sophisticated video game engines can be used to let people virtually ‘inhabit’ the digitally recreated world; and the experience can be made accessible via the Internet, opening it up to people who otherwise would never be exposed to these cultural sites. Yet, like every medium ever used to preserve cultural heritage, digital media is not neutral: it impacts the represented content and the ways the audience interprets it. Perhaps more than any older technology, it has the potential to affect the very meaning of the represented content in terms of the cultural image it creates. This paper examines the applications and implications of digital media for the recreation and communication of cultural heritage, drawing specifically on the lessons learned from a virtual reality project to recreate the thriving jazz and blues club scene in West Oakland, California, in the 1940s and 1950s.

Introduction

Cultural heritage sites all over the world face rapid decline due to aggressive urban development, wars, and general neglect. In places where resources are available for their maintenance, emphasis is largely given to preservation of and improving access to major sites that have fallen into disuse, such as old palaces and temples. In other places, artefacts are moved into sometimes remote museums, thereby separated from the context in which they were found. Neither approach preserves the vibrant life of the heritage – the way it appeared when the site was inhabited. Paintings or dioramas are only static two- or three-dimensional representations. Epic movies dramatise certain aspects of the heritage, chosen by the director, but are presented to audiences as only a passive, detached experience. As a result, examples of living heritage, such as buildings in use, traditional everyday life and special ceremonies, are at high risk of becoming lost.

A technology-driven alternative to preserving cultural heritage has emerged through the advent of new, digital media. Individual researchers, professional societies, museums, universities, and governments have embraced the modelling and visualisation abilities afforded by computers to create databases and actual reconstructions of threatened or altogether lost cultural heritage. These efforts have typically focused on the sites themselves, in the form of models of buildings and other structures, and the documents and artefacts found therein.

But the new technology has the potential to move the state of the art of cultural heritage preservation beyond static three-dimensional displays, capturing in interactive, game-like form the social, cultural, and human aspects of the sites and the societies that inhabited them. In so doing, the technology provides viewers with a measure of presence in the site, allowing them to participate in events, interact with representations of the former inhabitants of the place, and meet fellow visitors. It has the potential to transform the experience from passive viewing to active participation, albeit a game-like one.

Paradoxically, the relative ease of creating digital reconstructions, and the media-added data management and communication capabilities, have accentuated and brought to the fore two questions that have been dogging cultural heritage preservation all along:

Both questions pertain to current practices and future directions in which the scope and nature of digital media can be re-defined and expanded in the service of cultural heritage preservation. They also emphasise that the choice of media has an impact on the content it represents, and seek to understand those impacts in relation to cultural heritage. The two questions are not independent of each other: the affordances of the media dictate to a large extent what form the preservation will assume, and that in turn impacts and defines the cultural content itself. This paper examines these questions, illustrated through the digital reconstruction of the jazz and blues club scene in Oakland , California , during its hey-day in the 1940s and 1950s. The project was a joint effort by graduate students in the UC Berkeley Architecture Department and students in a class at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism.

West Oakland

In the 1940s and 1950s, Seventh Street in West Oakland was a bustling commercial district, anchored by dozens of jazz and blues clubs that earned a reputation as a West Coast rival of the Harlem music scene. The clubs were a Mecca for musicians from around the country who made West Oakland an essential stop on their tours. Most of the legendary blues and jazz singers and musicians, as well as soul and rhythm and blues artists, performed at the clubs, including Jimmie Witherspoon, Sugar Pie DeSanto, Ivory Joe Hunter, Lowell Fulson, Saunders King (Carlos Santana’s father-in-law), B. B. King and Aretha Franklin. The centrepiece of the club scene was Slim Jenkins Place, a sprawling upscale establishment that took up much of a city block with its huge dining area and elegant bar. Other clubs like Esther’s Orbit Room, John Singer’s, Moon’s, Harvey’s Rex Club, the House of Joy and the 49er Club also crowded the street, and virtually every café had a juke box blaring out the jazz and blues songs of the time. Many musicians got their start performing at the Seventh Street clubs, defining a distinct Oakland blues sound and cutting their first records with local music promoters like Bob Geddins and his Big Town recording studio and production company.

Complementing the clubs were numerous other business establishments up and down an eight-block stretch of Seventh Street—restaurants and cafés, clothing and drug stores, a movie theatre and a bowling alley, grocery and liquor stores, pawn shops and pool halls, hotels and boxing gyms—all of which made Seventh Street one of Oakland’s major commercial and retail centres at the time. Walk down the street and you would encounter any number of colourful local characters, such as ‘The Reverend’ who, along with his wife, preached from street corners; the ‘Tamale Man’, who pushed a cart up and down the street hawking his hot tamales to people pouring out of the clubs in the early morning hours; or Charles ‘Raincoat Jones’, a former bootlegger turned loan shark and dice game operator, who was known as the unofficial mayor of Seventh Street and helped finance some of the jazz and blues clubs.

Seventh Street had blossomed in the post-World-War-II era because of its proximity to Oakland’s waterfront, where workers had migrated from around the country to work in the naval shipyards during the war and sailors and soldiers were stationed at the military bases along the bay. Many of them then settled in West Oakland during the post-War era, including a large number of African Americans from the South who brought with them the jazz and blues sounds from states like Louisiana and Texas. West Oakland also was the terminus of the transcontinental railroad and the West Coast headquarters of the International Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first national black union. Many of the porters made their homes in Oakland, and they also served as a distribution network for the Seventh Street music, taking records cut by local artists and transporting them on the railcars for sale in cities across the country.

Fig. 1. Slim Jenkins bar/restaurant, West Oakland, c. 1950. Photo courtesy of the African American Museum and Library at Oakland.

While it was the influence of African Americans migrating from the South that defined the Seventh Street music scene, the population and culture of the area were very diverse. Greeks, Italians, Chinese, Latinos and people from many other ethnic backgrounds lived, worked and owned shops and businesses on and around Seventh Street. While de facto segregation was prevalent in other areas of Oakland, West Oaklanders prided themselves on their diversity and the relative lack of racial animosity in their community.

By the mid 1960s this remarkable part of Oakland ‘s heritage was all but destroyed, the victim of a number of different urban redevelopment schemes over the years. Hundreds of the elegant Victorian homes in the area that had fallen into disrepair had been torn down and replaced with large housing projects in the late 1930s and 1940s. In the 1950s the Cypress Freeway was built, an elevated highway that sliced across Seventh Street and effectively isolated it from the city’s downtown. In the 1960s the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) rail and subway system was constructed, including a rail line down the middle of Seventh Street. While the downtown Oakland rail lines were underground, an elevated structure was built along Seventh Street, creating a huge eyesore and deafening noise from passing trains. The BART line, which had a station on Seventh Street, and the freeway, which had exit and entrance ramps near Seventh Street, were touted as transportation arteries that would connect West Oakland to the rest of the Bay Area. Instead they had the effect of slowly choking off and degrading the Seventh Street commercial district and especially the music club scene.

Fig. 2. The low-bidder for the demolition of Seventh Street used a surplus World War II Sherman tank to raze the house, c. 1950. Photo courtesy of The Oakland Tribune.

The clubs also were the target of city building code enforcement crackdowns by city officials who viewed the clubs as sources of vice and crime. Finally in the 1960s, a stretch of several blocks along one side of Seventh Street was levelled to make way for a mammoth 12-square-block U.S. Postal Service distribution facility. A surplus World War II Sherman tank was used to demolish the old Victorian homes along side streets and make way for the postal facility. While the facility was trumpeted as a source of more than a thousand new jobs, the vast majority of those were filled by transferees from other postal facilities and only a relative handful of jobs went to West Oakland residents.

Today, a walk down Seventh Street reveals almost no hint of the vitality of the area and the once thriving jazz and blues club scene. The street is marked by boarded up buildings and empty lots and plagued by drug dealing and crime. Slim Jenkins Place, the hallmark of the blues and jazz era, has been torn down and in its place is Slim Jenkins Court, a modest low-income housing project with a plaque outside denoting its name-sake. The only remaining music club from the 1950s is Esther’s Orbit Room. The Cypress Freeway structure, which collapsed during the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, was torn down and the freeway re-routed around Seventh Street, because of community pressure to eliminate the barrier it had posed between Seventh Street and the rest of the city. Despite that, and numerous other proposals to revitalise the area, only a scattering of businesses now exist along Seventh Street.

The story of Seventh Street has been told in bits and pieces over the years in a variety of different media. Newspaper stories have been written about West Oakland and the club scene, usually from the perspective of music lovers re-living Seventh Street ‘s glory days or in the context of efforts to revitalise the area and the lessons learned from the redevelopment projects that destroyed it.1 More than a dozen books on Oakland or on jazz and blues music have included segments describing the Seventh Street clubs or the redevelopment projects that caused their demise. The Seventh Street club scene was a main subject of two documentary films, Crossroads: A Story of West Oakland and The Story of the Oakland Blues.

Various reports done for governmental agencies have recounted the history of Seventh Street and its decline.2 A couple of different oral history projects have preserved in audio interviews the remembrances of some of the key figures in the Seventh Street scene, such as singer Sugar Pie DeSanto and C.L. Dellums, a major leader in Oakland of the International Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, who were interviewed for an oral history project at UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library. A few photo collections exist, such as the Slim Jenkins Collection and the C. L. Dellums Collection at the African American Museum and Library at Oakland. A Web search of various keywords relating to Seventh Street or the Oakland jazz and blues music similarly will yield numerous different websites with information on the music scene there or on the rise and decline of the Seventh Street commercial district.

But none of these have told the story of the clubs and what happened to them in a comprehensive way. And most importantly, these media tell the story in a detached or visceral way that does not allow the reader or viewer to truly ‘experience’ what Seventh Street was like. Newspaper stories, books and other printed formats can only employ descriptive terms or accompanying photographs to evoke what some of the characters on Seventh Street may have been like as people, leaving the reader’s imagination to fill in the blanks. The print medium cannot possibly convey what the experience would have been to talk to and interact with these characters or explore the music scene on Seventh Street . Oral histories, or even video interviews, of some of the characters from Seventh Street provide first-person and often highly emotive descriptions of what the people and the Seventh Street scene were like. But these too are records about life on Seventh Street, and still require the listener/viewer to use his/her imagination to conjure up images of what the characters and their surroundings looked like decades ago. The listener/viewer remains detached from, rather than immersed in, the experience of Seventh Street.

Photographic collections and documentaries provide a visual and sometimes highly emotive record of aspects of Seventh Street, but only in the form of static images (no videos from the era are available) accompanied by narration, interviews and sound tracks that can’t truly capture the dynamism of what it would have been like to ‘live’ in the Seventh Street scene. The viewing experience also is passive, and in the case of the documentary requires the viewer to follow a linear storyline imposed by the filmmaker, with no way to venture out and explore Seventh Street on your own terms. Digital technology such as the Internet seemingly would allow a person to bring together many of these disparate media elements—a photo here, a piece of music there, some descriptive text at another site—to learn the story of Seventh Street. But search technology only maximises the interactive capabilities of the Internet, empowering the user to assemble a large catalogue of information from which a story might be pieced together. And even if these pieces were reassembled in one space, such as a website, the experience would still be a fragmentary one, perusing different segments of a story presented in different media forms. The potential for immersion in and experience of a special place remain elusive.

To recreate, as faithfully as possible, the experience of what Seventh Street was like requires a digital technology that is both interactive, allowing choice by the user, and immersive, using visual and audio stimuli simultaneously to give the user the sense of being in a place. In short, a new media technology that replicates a person’s real-life experience of moving about within the world.3

Choosing the right metaphor

The convergence of the desire to re-tell the history of Seventh Street and the advent of new media have provided us with the opportunity to develop an immersive, interactive, non-linear narrative that will help visitors experience Seventh Street’s cultural heritage as it was in the 1940s and 1950s. But the question of which exact type of new media technology to use, and what is the appropriate manner of using it, became immediately apparent. Digital gaming—the new media technology we thought would be useful for this purpose—provided no useful clues in and of itself: it is a new technology, one with a relatively short history, and devoid of much in the way of comprehensive theory or many useful precedents to guide its development.4 Although in principle it is a cross between filmmaking and architectural design, it is a technology of illusion, creating an intangible reality like never before. Unlike architecture, whose principles it freely borrows, it can only be inhabited by proxy. Unlike film, it provides visitors or players (terms like ‘viewer’ are inadequate) with much more freedom to explore the ‘world’ at their own volition.

To help us understand how video game technology could and should be used to create a virtual world, we chose to use the all-encompassing metaphor of place. According to Martin Heidegger, “Place places man in such a way that it reveals the external bonds of his existence, and at the same time the depth of his freedom and reality.” 5 More conventionally, a ‘place’ is a setting that affords the entire spectrum of human activities, including physical, social, and cultural activities, while affecting, and being affected by, those activities. The advantage of using this metaphor to guide our work is that it pertains to both physical and non-physical settings:

“The word place is often used to describe the larger territory that we build. The boundaries of this territory are defined by a sense of being inside—inside a region, a town, a neighborhood. The boundary is identified not by a demarcation of its edge but by the feeling of coherence of the spaces and the buildings within it, which give rise to a competence in the way a place is built and inhabited. We value such places for their qualities as extended environments and the support they give to our inhabitation. We value the feeling of being somewhere as opposed to just anywhere”.6

‘Place’ is as much a psychological phenomenon as it is a physical one. It is rooted in human social action and cultural conceptions: “a place is a space activated by social interactions, and invested with culturally-based understandings of behavioral appropriateness”.7 Or, as Bertrand Russell famously proclaimed, “Indeed the whole notion that one is always in some definite ‘place’ is due to the fortunate immobility of most of the large objects on the earth’s surface. The idea of ‘place’ is only a rough practical approximation: there is nothing [physical] logically necessary about it, and it cannot be made precise.”8

‘Placeness’ is the consequence of the activities and conceptions of the inhabitants of a space. The physical attributes of the place frame those activities, and provide its inhabitants with a socially shareable setting for their activities, in terms of cues that organise and direct appropriate social behaviour in that particular place. It is because the spatial organization offered by the physical setting that comprises a place, and by the spaces it defines, are the same for all the actors, that several people can engage in similar activities. They have a shared ‘sense of place.’ This shared understanding helps them to orient themselves with respect to the space they occupy and with respect to each other, and thereby establish social references that direct their behaviour in a way that gives meaning to their activities.

‘Place,’ of course, has many more qualities than affording a shared social setting and directing behaviour. Place is unique: there are no two places that are alike, no matter how similar they may look. Their uniqueness comes from internal characteristics (location), and from external characteristics (situation)—their relatedness to other socio-spatial determinants (economics, geography, etc.). Although unique, places are not detached: they are connected, physically and conceptually, to other places. It is this connectedness that allows us to ‘know’ how to behave, for example, in a fast food restaurant in Des Moines, Iowa, even if we have never visited that particular establishment before. Places have history: past, present, and future. They grow, flourish, and decline, along with the site and the culture in which they are embedded.

Most of all, places have meaning, which is based on the beliefs people associate with them. It is this meaning that determines the expectations of human behaviour in a ‘place’ (which, when violated, is considered to be ‘out of place’). These meanings arise over time as practices emerge and are transformed within the cultures that use them. Different cultures may have different understandings of similar places and similar concepts, which contributes to the feeling of estrangement when visiting foreign countries, where the same cues have acquired different meanings than back home.

It is for all these attributes, and the fact that architects are experienced in making places, that we chose this metaphor to guide our work. Still, architects are accustomed to developing only one aspect of place: the setting, or physical context, which provides the ‘stage’ for some human activity. This setting must conform to and support the activities and conceptions associated with the place, which in the case of physical architecture are often dictated by the client, by the function of the place, and by the social, cultural, economic, legal, and other circumstances associated with it.

Not so in the case of a virtual place: although it is logical to assume that designing virtual places can, indeed must, be informed by the principles that guide physical place-making, many of the constraints that form the basis of physical places do not apply to virtual places. Making virtual places is not a matter of simply emulating physical form in electronic environments. Objects and spaces that were functionally and conceptually ‘appropriate’ in the physical world lose their appropriateness in Cyberspace: there is no gravity, wind, or rain. Solid objects can easily intersect, and large distances can be traversed instantaneously. Still, having been conditioned from birth to function and perceive the physical world, we carry the expectations and sense of ‘appropriateness’ to Cyberspace. We may, then, be frustrated that we cannot actually ‘touch’ a wall, sit on a bench, or feel the weight of an object. On the other hand, we may well want to take advantage of the affordances of the virtual world: fly when we feel like doing so, eavesdrop on the conversation of strangers, even hide our persona behind a borrowed avatar. The impression such freedom produces can be quite surreal, thereby interfering with the creation of a desired ‘sense of place’. Hence, choosing the right balance between emulating real, but unnecessary settings, versus providing possible, but unnatural abilities, to engender the desired sense of place, while not falling into the traps of indiscriminate ‘borrowing’ from physical space or discarding everything we learned from it, is the challenge facing virtual place-making.

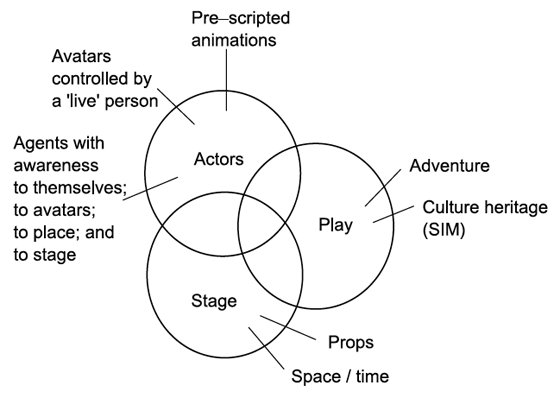

To help us navigate these differences, we chose to compare our virtual place-making to making stage-plays. These comprises a stage (a context), a narrative (the play), and actors (which include the audience, in different ways). The notion of place as a stage-play drives literary works, films, video games and architecture. It provides a framework for understanding the individual contributions of the components, and their mutual interactions. The following diagram illustrates the components and their relationships:

The components of this model include:

The ‘stage’—or context—which comprises both space and time. It affords spatial and temporal grounding for the entire enterprise, and includes:

The ‘actors,’ which include:

The ‘play’—or content—which includes both cultural heritage aspects, and the activities that take place in the environment (known together as simulation/action). They tell the story (or stories) and afford the freedom to participate in the story.

The interactions between these components are what make them a ‘place’: the PC avatars, which are the representations of the visitors, can ‘see’ other avatars (as well as the other components of the game), and be ‘seen’ by them. Hence, if one raises its hand, others will see the action and react to it, generating a kind of social awareness. Likewise, the NPC agents can be seen by the visitors, and can react to their presence. This reaction both conveys some of the essence of the cultural heritage (they can tell stories related to the history of the place), and add to authenticity and ‘sense of place’ of the experience. And of course the context (buildings, cars, etc.) help locate the experience, both spatially and temporally.

The ‘stage’

The first problem facing digital reconstruction of a cultural heritage site is finding the appropriate documentation that describes the built environment and the ‘props’ for the period being reconstructed. In many cases, some buildings exist. They can be photographed, measured, or digitally scanned, providing a basis for the reconstruction. In other cases—such as West Oakland —extensive urban development has literally obliterated entire blocks of buildings, and significantly modified the remaining ones. The recourse, of course, is finding period photographs that depict the built environment at the time.

Surprisingly, this proved to be a difficult task in our case. While a number of different libraries, museums, public agencies and news media had photo archives of Oakland, getting street scenes of Seventh Street from the 1940s and 1950s proved very problematic:

We also wrote stories for the Oakland Post newspaper and the San Francisco Chronicle and did a program for a local radio station about our project, which included requests for members of the public who had photographs of Seventh Street to submit them to us. Other publications, such as the Contra Costa Times newspaper (which serves cities near Oakland) and California Monthly magazine (the alumni publication for UC Berkeley) also ran stories about our project. These efforts yielded some photographs, but most were portraits of people of the era, rather than street scenes.

Finally, we reached out to the community in two different meetings of Seventh Street ‘old timers’ organised and promoted by the Oakland Post. These also included requests for any old photos the people attending the meetings might be able to provide. This again produced some photographs, but mostly of individuals, rather than the buildings or the general street scene along Seventh Street.

We plan to continue our efforts to obtain photographs, going back to some of the sources already mentioned, in particular the Oakland Museum, and identifying other possible archives. But a lesson learned was that while a wealth of written and oral documentation might be available about the history of a cultural heritage site, such as was the case with Oakland’s Seventh Street, obtaining a comprehensive contemporaneous photographic record of what the site looked like even only 50 or so years ago could prove very difficult and time-consuming.

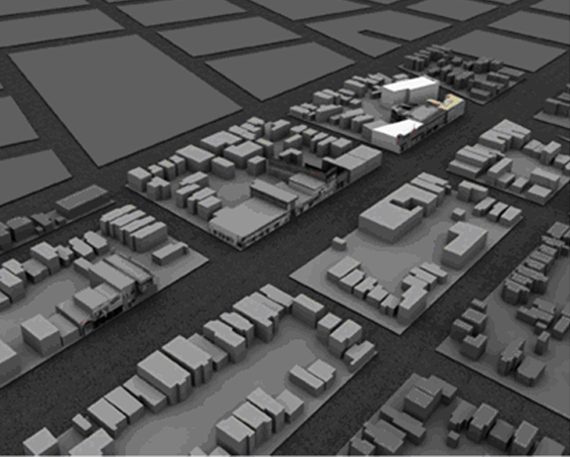

Fig. 3. Bird’s-eye view of the model.

As a result, at least in the initial phase of our project the recreation of many of the buildings on Seventh Street had to rely in large part on using photographs of a few blocks of Seventh Street or of other nearby commercial streets from the 1940s and 1950s to produce generic representations of the building. The exceptions were Slim Jenkins Place, for which we had a good set of photographs, and a few dozen other buildings for which we had photographs from the 1940s or 1950s, or at least the Planning Department photographs from the 1980s.

The development of the eight city blocks comprising the target of our study then became a matter of modelling buildings, street furniture, and other ‘props’ in 3DStudioMax, a conventional modelling software. This approach was both convenient, building on our familiarity in modelling with 3DMax, and because the software that we chose to power our virtual place was the game engine Torque, which accepts 3DMax models.

Using the Torque engine9, made by Garage Games, to power our virtual world provided many advantages: it incorporates a physics engine, whereby ‘gravity’ is imposed, solidity of objects can be enforced, and time of day and weather phenomena can be included. Torque also provides mechanisms to support PCs and NPCs (player characters and non-player characters), which were useful for implementing the actors, as discussed in the next section.

Still, many more decisions needed to be made, to fit the ‘stage’ with the intended action and the actors. For example, all our photographs from the 1940s and 1950s were in black and white (grayscale). We decided, therefore, that all buildings will be rendered in gray scale. The time of day was set to be early evening, while there is still enough light to see objects and characters clearly, but late enough to support the story line when bars are open.

The ‘actors’

The second main challenge in developing the virtual world was character development, both physical and literary. The physical challenge has been mostly technical—modelling human beings is difficult, because we are so accustomed to seeing them in real life that any discrepancy is immediately, and disturbingly, obvious. In the case of West Oakland, we needed to develop a wide range of characters, both avatars for the player character visitors and ‘bots’ for the non-player characters (the NPCs), who would resemble some of the real people who inhabited Seventh Street in the 1940s and 1950s. We relied, again, on photographs, which in this case proved to be plentiful. Unlike the dearth of photographs of buildings on Seventh Street, many photos of the characters who worked on Seventh Street (especially musicians and club owners) were available from the various archives described above. Additional photos were provided by some of the still living residents of the area. And other photographic collections existed that showed the general fashions and hair styles of the era, which could be used in constructing the PCs for players and generic NPCs to populate the street.

There also was a wealth of information available for the characters’ literary development—that is for creating realistic personas for the NPCs. Newspaper stories, primarily from the Oakland Tribune, had detailed biographical information on many of the musicians, club and business owners and other characters on Seventh Street. The Internet similarly had many stories and other documents posted at various websites that contained descriptions of Seventh Street characters, especially biographies of the more famous jazz and blues musicians and singers posted at music sites. But most important were the memories of people who lived or worked on Seventh Street or in nearby neighbourhoods who were interviewed for the project. Many of them we were able to track down from leads provided by the Seventh Street ‘old timers’ that we initially interviewed for the project at the meetings set up by the Oakland Post. More than a dozen other people contacted us, usually in response to one of the stories publicising the project. Some had almost encyclopaedic memories of the area during the 1940s and 1950s, describing the personalities of many Seventh Street characters, the ambience of particular clubs, the many shops and stores along the street and their owners, and other aspects of the Seventh Street scene. In short, we had a large amount of biographical information on dozens of musicians, club and business owners and other prominent people to help with character development.

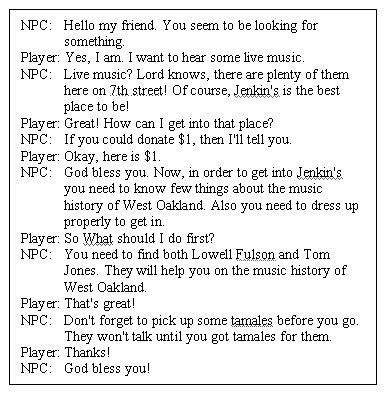

We incorporated this into the game by writing interactive dialogues in which the player could engage in a conversation with an NPC, and ask a series of questions that would prompt the NPC to recount details about their personal history. In other cases an NPC was created to engage in conversation with the player and provide biographical titbits about another Seventh Street character. Thus the player could learn about many of the main characters of Seventh Street—Raincoat Jones, Slim Jenkins, Sugar Pie DeSanto, C. L. Dellums—by engaging them in conversation directly or by interacting with other NPCs who would provide some biographical information about the characters.

A bigger challenge was developing the literary ‘persona’ of each NPC. It was our intent from the beginning to tell the story of Seventh Street as much as possible through these NPCs. This included not only delivering the factual parts of the history of Seventh Street , but also its flavour. This flavour, which is a major component of the ‘sense of place,’ is intimately intertwined with the characters—how they talked and the particular colloquialisms they used, how they behaved, such as whether they were animated and funny or sombre and gloomy, and so on. In a video game environment, this flavour of the characters usually emerges from the interaction between the player and the NPC.10

Fig. 4. Avatars and NPCs.

Fig. 5. Sample dialogue between a Player and an NPC (Non Player Character, the Reverend, in this case).

This raised an interesting issue in character development: to what degree were we bound by the verifiable, factual biographical information we had learned about a Seventh Street character in developing its corresponding NPC, and to what degree were we allowed to interpolate the persona of that NPC as it would emerge in an interactive dialog with the player? In most video games, characters are almost wholly fictional.11 Fiction allows the developer to invent aspects of a character or the game world to improve game play, make a character more compelling or make the interaction between player and character more natural or meaningful.

But our project was an attempt to portray Seventh Street and the people there in as authentic a way as possible. In a standard journalistic treatment, this would be done by writing in the third person and specifically attributing any biographical information about a character to others who know him or her or to direct observation. But this wasn’t possible in a video game story, where an NPC’s background was disclosed in first-person interactions with the player. We thus could not inject the attribution for biographical information into such interactions without ruining the game play experience. We also needed to develop personalities for the Seventh Street characters so they wouldn’t be lifeless cardboard cutouts, but rather more like ‘real’ people who revealed themselves in conversations and other interactions with the player. But these personas could not possibly be truly realistic, as we only had other people’s often vague recollections of a particular character’s behaviour, personality traits or speech patterns, or in a few cases where a central character was still alive, that person’s recollections of what they were like as a person 40 or 50 years ago or more. So what were the limits on ‘filling in’ a character’s personality? Could the NPC be open and friendly with the player, when the real character might have been socially shy or reclusive? Could the NPC tell a clever joke to make interaction with the player more interesting, or was this only permissible if we knew the actual character was a jokester or prankster? Could the particular words and colloquialisms we had an NPC use in conversations be dictated by what best fit with that moment in the game play? Or were we restricted to only using words and phrases the real character had used? Faced with these dilemmas we adopted some rules for character development for the NPCs in the game world that were based on real people:

The case of Sugar Pie DeSanto, a prominent blues singer who performed at the Seventh Street clubs, illustrates this approach. For information about her background and her observations about Seventh Street and its music scene, we drew on quotations from her that had been published in various news stories, and an oral history done of her for a UC Berkeley Bancroft Library project. In most cases, we simply used her exact words from the audio recording or as quoted in the news stories when we wrote conversations between her NPC and the player in the game. Some minor wording might be changed to smooth out the interaction, such as tense (since the quotations from Sugar Pie DeSanto in the stories and the oral history were her reflections on what she had done on Seventh Street, whereas in the game world the player’s interaction with DeSanto’s character was in present tense).

Some of the aspects of her persona similarly were drawn from the way she spoke in the oral history or from what others who knew her said about her personality.

But much of the conversational back-and-forth between DeSanto’s character and the player was not a portrayal of how DeSanto actually talked and acted, but words or gestures that had to be filled in to make the interaction seem as natural as possible.12