More on Virtual Reality & Storytelling Continued

The ‘play’

Finally, the component that brings everything together, is the activity, or ‘play.’ What does the player do in the virtual world and game environment, and how are all those actions and interactions tied together in a larger experience of the meaning of the virtual world and the story that unravels about it? In the case of the Seventh Street project we tried to do this by creating both individual ‘quests’—small missions the player must accomplish in order to learn the history of Seventh Street, and developing an overall narrative that tied these individual quests together in some meaningful way.

The latter issue of the larger narrative begged the question of what genre of video game13 we wanted to employ to provide a structure for game play and a meaningful experience for the player. One possibility was a ‘simulation’ game, in which the virtual world is based on a real world and the player finds meaning by mimicking some of the real-world activities in the virtual world environment. Many such simulation games take this a step further and allow the player to significantly alter or re-construct part of the virtual world or their own character (the SIMS is a prime example of this). While our recreation of Seventh Street as a virtual world obviously had strong elements of simulation games, we decided for at least the initial phase of the game to not allow the player to make significant changes in the game world. To do so would have posed a major technical issue—providing the software tools needed by the player to re-create the game world.14 But more importantly, allowing players to alter the game world could undermine one of the main purposes of our game, which was to re-create as accurately as possible what Seventh Street and the characters there were really like.

Players might create characters that would not have been present on Seventh Street in the 1940s and 1950s and would look out of place to other players of the game. Or they might create a music club that played modern music, not the blues and jazz of the era, which again might diminish the game experience for other players. Thus while our game drew on aspects of simulation games, such as the player’s deriving meaning from re-living what it was like to have been on Seventh Street in the 1940s and 1950s, we deferred giving the player the ability to alter that world until we could define what changes could be made that still preserved the integrity of the game experience for other players.

Fig. 6. A street image, with players and NPCs engaged in various activities.

A second genre of video game play that had obvious application to our project was the multi-player game. From the beginning of our project we had decided that our game should be multi-player, allowing many people to log in to the game at the same time and interact with each other in the virtual world. This was in part because Seventh Street was very much a social scene, and our game therefore needed to be a social experience. Making the game multiplayer also promised to provide a richer experience because of the different types of people who might be drawn to the game—’old-timers’ who wanted to relive their experiences of Seventh Street, school children who enjoyed game play and could learn about part of their heritage, and jazz and blues fans wanting to explore the music of the era. But multi-player games, particularly massively multi-player ones like EverQuest or World of Warcraft, also often include the ability for players to join with each other in common tasks to heighten the social experience and add further meaning to game play. Thus players might form guilds and then go on joint expeditions or engage in competition or even combat with other groups. In our game, this could mean allowing players to band together as club owners and musicians and compete with other players who represented the government agencies sponsoring the redevelopment projects that led to the clubs’ demise. But this immediately raised a question similar to the one we encountered with the simulation game genre and the player’s ability to change the ‘reality’ of Seventh Street . If groups competed with each other over the fate of Seventh Street, that would require writing a version of the history of Seventh Street that did not occur—one in which the clubs and music scene survived and flourished. This raised a host of difficult questions about how individual development decisions affected the fate of any particular club or of the clubs in general, what the cumulative effects of those decisions were and what alternatives existed. To create a game that was a realistic representation of what might have occurred on Seventh Street would require analysing the usually contentious debates over the effects of urban planning decisions and then translating those into the relatively simplified choices that characterise game play.15 Because of these complexities, we again deferred for the initial phase of the game employing the more sophisticated group play elements of multi-player games, relying instead on basic social interaction among players to add additional meaning to our game experience.

The third genre of video game that had obvious application to our project was the adventure game. In adventure games, the player usually explores a virtual world and gradually unravels the mystery of that world through a series of tasks and quests. One of the most classic adventure games was Myst, one of the most successful video games ever (although adventure games have declined in popularity with the public and game developers in more recent years). In an adventure game, meaning is derived from navigating through the virtual world, interacting with a series of characters and objects that yield clues about the nature of the world, and finally piecing those together to solve a larger puzzle about the world or gain a deeper understanding of it. This was a natural fit with our conception of the Seventh Street project and thus was the main approach we took in designing the initial phase of the game—giving the player a series of tasks that could be performed to gain a sense of what the Seventh Street scene was like and to learn about the forces that prompted the decline of the clubs.

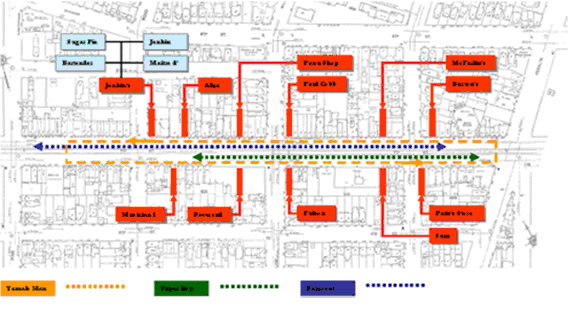

Fig. 7. The spatial layout of the quests along Seventh Street.

To implement this approach, students in the journalism class wrote a series of interactive narratives, which we called ‘quests,’ in which the player would interact with NPCs or objects to learn about various aspects of the Seventh Street scene or the development projects that threatened the area. Some of these quests were very simple and essentially linear. The player would encounter an NPC and be allowed to ask a question using a chat feature of the game engine. The NPC would respond, and that would open up the chance to ask a second question to which the NPC would respond, and so on. From this interchange, the player would learn about the NPC or about some other aspect of Seventh Street.These simple quests initially did not take full advantage of game play, such as offering the player multiple choices for how to interact with the NPC. So later, after many of these simple quests had been written by the journalism students, the architecture students began taking each quest and re-writing the dialog between the player and the NPC, so the player had the option of asking several different questions during the first encounter. That then would produce responses that opened up multiple follow-up questions by the player, until all the information from the NPC had been provided to the player. Thus the player could choose to ask about a particular aspect of an NPC’s ‘life,’ and then choose to inquire about another aspect of the NPC’s background, with the game engine tracking what had been asked and answered, and thus what questions and information remained to be conveyed, until all had been exhausted. This approach made the player/NPC interactions less linear and increased game play by providing the player with multiple routes through which an NPC’s background could be explored.

Other more intricate quests also were written by students in the journalism class, leading the player through a series of interactions with NPCs and objects, and at each point presenting the player with options on what questions to ask or what steps to take to proceed with the quest.

The game engine again would track the player’s choices, providing options to the player depending on whether the player had finished certain tasks (such as asking an NPC a particular question or picking up and examining an object such as a map). These quests were much more non-linear and game-like, providing choices for the player that drew her through various stages of the quest until the ultimate goal was reached and the quest completed.

For example, one quest involved the player learning and helping inform the local community about the Cypress Freeway that was being constructed across Seventh Street in the late 1950s, isolating the community from downtown Oakland and contributing to the street’s decline. This quest began with the player conversing with two NPCs, who represented local residents who had heard something about the freeway construction but wanted more information. They prompted the player to go to a location where there were two NPCs, a surveyor and a California Department of Transportation official. The player could converse with each of these NPCs in any order. But the extent of the information provided by the Department of Transportation official about the freeway project was contingent on the player having already conversed with the surveyor and also having obtained from the surveyor a combination lock to a toolbox that contained a map of the proposed freeway. When the player completed all of these tasks, the player could return to the two local resident NPCs, relay the information learned from the surveyor and the Transportation official and provide the residents with the map. The two residents promised to spread the word among others on Seventh Street about the help the player had provided. The player’s reward was to obtain a ‘community service credit’ (added to an inventory for the player tracked by the game engine), which then would gain the player access to other NPCs who could provide other details about Seventh Street (these NPCs presumably having been notified by the residents of the player’s help in uncovering what was happening with the Cypress Freeway, and thus being more willing to talk with the player).

In another quest, the player attempts to gain access to the dining and musical performance area of Slim Jenkins Place, the premiere jazz and blues club on Seventh Street that was very upscale and had an informal dress code. The player’s access is blocked by a maître’d, who informs the player that he/she can go to the bar area of the club, but he/she is not appropriately dressed to enter the more formal dining area. The maître’d instructs the player that he/she will have to obtain a shoeshine and a new set of clothes to gain entrance, and then generally points the player to the location of a shoeshine stand. The player then can interact with an NPC who is a shoeshine boy (the shoeshine character was based on a person interviewed for the project who had been a shoeshine boy on Seventh Street), obtain a shoeshine, and then get directed by the shoeshine NPC to Burton’s clothing store elsewhere on Seventh Street (modelled after Burton’s, a fashionable clothing store that existed on Seventh Street). The player then can enter the clothing store, interact with an NPC representing the manager of the store, and purchase a new outfit. In one final twist, the clothing store manager will ask the player for a cigarette. If, on they way to the store, the player had noticed and picked up an expensive cigarette case lying on the street, the player then could offer it to the store manager. In exchange the store manager would describe to the player the two uses that could be made of the cigarette case, either keeping it and using it as a conversation opener with other NPCs on Seventh Street , or pawning it to obtain money to spend. Finally, the player then can return to Slim Jenkins Place and is now admitted by the maître’d to the dining and performance areas of the club.

The need for money was an element that was built into several of the game quests. In the Slim Jenkins/shoeshine/clothing store quest, a certain amount of money was required of the player in order to pay for the shoeshine or purchase an outfit at the clothing store. Without the required money, the player would be unable to complete those steps in the quest. Instead the shoeshine boy and the clothing store owner would indicate to the player the ways the player could obtain the needed money. Other quests then were developed as devices for the player to obtain money. They included going to a pawnshop and pawning an item in the player’s inventory (such as the cigarette case mentioned above), participating in a dice game (which included a randomizing feature that allowed the player to win some games and lose others), getting a job at one of the clubs, getting a bank loan, or getting a loan from Charles ‘Raincoat’ Jones, the notorious loan shark of Seventh Street (these latter three money quests are still being developed).

The Cypress Freeway and the access to Slim Jenkins Place quests each thus involved multiple interrelated steps. Several other complicated quests like this also were written. And the Slim Jenkins Place quest and other quests included components that required obtaining money, so those quests would be connected to the money quests, and one could not be completed without the other. Finally, in these quests and also in the simpler quests, hints were included in the dialog with an NPC about other aspects of Seventh Street , thus pointing the player to other quests that might be performed to learn about Seventh Street and the forces that would destroy it.

But otherwise the quests written for the first phase of the project were kept independent of one another, so completion of one quest did not require completion of another. Nor was any particular order imposed on how the player should go about completing the different quests. Instead a more ‘modular’ approach to game play was used, in which the player generally could choose which quests to pursue and the order in which to pursue them.16 And the overall game scheme did not follow a linear progression from one level of play to another, such as requiring that a sequence of quests be performed in order to open up a new sequence of quests. Keeping the various quests independent of one another made writing the elements of the game narrative much less time-consuming, as each quest didn’t have to include different storylines depending on what other quests the player had or had not completed. It also made ‘playing’ the game easier for people who might only want to learn about Seventh Street, and did not want to be forced to go through a complicated series of steps to gain knowledge about a club or character (an approach we thought some of the older people who had lived on Seventh Street but were not particularly computer literate might prefer).

But this simplified approach proved unsatisfactory because it reduced the game experience to a somewhat rudimentary form. Players performing the quests had a quasi-game-like experience, involving interactive choices within a quest and, in a few cases, between some different quests. But, as noted above, we had not developed an overall scheme that tied all these elements together into a more linear progression that reflected a master storyline for the game. Architecture students then attempted to group together some of the quests and arrange them into stages, so certain quests had to be performed in order to gain access to another level of quests, which in turn led to a third level of quests and the ultimate completion of a portion of the game story. Thus the quest about accessing Slim Jenkins Place was restructured so it included not only going through the shoeshine stand and the clothing store, but a new sublevel of interactions with a record producer, a musician, a street vendor and a street-corner preacher. Each of the quests thus were directly related to the others, with the game engine tracking what the player had accomplished, and the narrative elements of the story rewritten and presented to the player according to what had previously been accomplished. Thus the nature of a conversation with the musician might be dependent on whether the player had already had a conversation with the preacher. And interactions with all four of the NPCs on this level of the game were required before the player could go on to the shoeshine and clothing store levels of the game.

This increased the degree of game play, but complicated the storytelling with a multitude of options that the narrative now had to take account of depending on what NPCs the player had interacted with and in what order. This threatened to make the story line more convoluted, as we tried to enhance game play by tying together a series of mini-narratives, while also creating an ad hoc narrative structure to superimpose on the game play. It also posed challenges for the character development of individual NPCs. Rather than an interaction with an NPC providing an opportunity for detailed knowledge about that NPC’s character (and thus getting to ‘know’ the character), the NPC often became more of a vehicle in the service of the game play. The NPC’s character then emerged in bits and pieces according to what point the player was at in the game. This problem underscored a long-standing tension in the video game world between game play and narrative. Some game developers are adamantly opposed to imposing a narrative on a game, arguing that it restricts and diminishes game play. Others, including video game writers, argue that understanding narrative techniques can enrich a game, in particular the characters within it.17

In our project narrative clearly was essential, as our original purpose was to tell the ‘story’ of the Seventh Street clubs and what happened to them. But game play was equally important. We had selected a video game as the best way to tell the story because it allowed people to truly experience Seventh Street as it was through meaningful game play, rather than simply producing an objectified linear narrative in one media form or another, or opting for a museum-like experience that would have a stage and actors, but no overall play. What is required is mapping out a particular narrative—a way of telling the story—and then drawing on the different aspects of video game play to help tell that story.

This has brought us back to the original question of how best to construct the ‘play’ using the various video game genres, and the challenges posed by each. Should we continue to use the adventure game approach, but write an overall narrative first about what Seventh Street was like and what happened to it, with the characters, quests and levels of game play stitched together within that framework? Is that narrative compelling enough to motivate people to want to play this game? Is simple curiosity or a desire to learn about or re-experience Seventh Street , its music and its history an alluring enough adventure? Or does the story instead need to be written more as a mystery to be solved (an aspect of most adventure game), with the player unlocking the secrets of Seventh Street and what led to its demise? Should we give the player the ability to change the course of history and make the game about saving Seventh Street (thus drawing on simulation games and the player’s ability to re-create aspects of the virtual world)? Or should we make the game more of a social experience and allow players to band together, perhaps in competition with one another to save or destroy Seventh Street (as in massively multi-player games)?

In the first phase of our project we constructed the stage for Seventh Street, we developed the characters in it, and we pieced together some of the scenes within that world. But the ‘play’ still remains to be written. The choices made will not only determine how we tell the story of Seventh Street, but the particular ways in which people will experience and understand Seventh Street and this aspect of Oakland’s cultural heritage.

Discussion

New media reconstructions of historically significant sites, artefacts, people and their activities bring new opportunities to the practice of preservation and the communication of cultural heritage. Visual verisimilitude, coupled with non-linear storytelling and interactivity, affect each aspect of the practice. But their critical implications are not limited to the technical aspects of cultural heritage representation. Rather, new media have the power to transform it, wholesale, possibly affecting the meaning of the heritage itself through the image created by the technology.

The relationship between a representational technology and the cultural heritage it communicates is as ancient as civilization itself. It can be traced back to cave drawings from the upper Paleolithic age, some 40,000 years ago, that supposedly were used to help bring about successful hunts. The oral epics of Homer and others were used as a social instrument to communicate cultural heritage from one generation to another, only to be replaced by written versions in the form of scrolls, and later by codices, each of which exerted its own influence through the process of remediation: while oral renditions allowed for variations due to the skills of the bard, written forms codified the story, creating an ‘official’ version. The invention of photography had a particularly strong impact on the representation of cultural heritage. The impact was even more profound with the invention of cinema—a medium able to capture the passage of time itself. The advent of digital game technology—the new medium of remediation—has the potential to affect cultural heritage in even more profound ways than before.

Like the Native American Ghost Dance of the 19th century, which was purported to invoke the return of dead warriors and restore a peaceful past before the advent of white settlers of American Western plains, new media is a technology that has the power to create world-altering experiences of places and times no longer accessible. In many ways they can halt, even reverse the inexorable march of history. But rather than a spiritual belief, new media create a tangible, shareable, participatory experience. It is an imagined, intangible experience, but a real one nonetheless. The image of history it communicates is mediated both through the technology itself, and through the authors and technicians who render it. This image is comprised of a collection of methods, habits, organizations, knowledge, and a culture of preservation. The authors and technicians who wield the storytelling power may know how something is done, but are not always aware of the values implicit in their particular way of rendering the narrative. New media experts (modellers, animators, programmers) are not trained as cultural preservationists themselves (with few exceptions). Their image of the practice of cultural heritage preservation is articulated in the assumptions they make about the kinds of methods and approaches needed to execute that practice. Thus both cultural heritage experts and new media specialists have the added responsibility to understand the implicit embodiment of the values associated with the practices and tools they use, and their influence in shaping cultural heritage.

Notes:

1. One such story, ‘West Oakland Revisited’, published in the Oakland Tribune on September 5, 1982 , was written by one of the co-authors of this paper, Paul Grabowicz, while he was a reporter there. The selection of the Seventh Street jazz and blues club scene for this cultural heritage reconstruction project is traceable to that story.![]()

2. See for example, Putting the ‘There’ There: Historical Archaeologies of West Oakland , a report prepared by the Anthropological Studies Center at Sonoma State University for the California Department of Transportation during the debate over a replacement route for the Cypress Freeway, http://www.sonoma.edu/asc/cypress/finalreport/index.htm (15 August 2006).![]()

3. On the interplay between interactivity and immersion in digital technology and human computer interaction, and how virtual realty might be used to construct a new narrative that encompasses both, see Murray, J. (1997), Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace, New York: The Free Press.![]()

4. There are many books on digital gaming, written mostly by practitioners of who report their success in implementing one game or another. There is little in the way of a deep theoretical study of digital gaming as a discipline, although many universities are beginning to treat it as such. For one effort to begin developing a theoretical framework for understanding gaming in general, see Salen, K. and Zimmerman, E. (2003), Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals, Cambridge, Massachussets: MIT Press.![]()

5. Heidegger, M. (1958), The Question of Being. Translated by Wilde, J. T. and Kluback, W., Albany, New York: New College University Press.![]()

6. Chastain T. and Elliott A. (1998). ‘Cultivating Design Competence: online support for beginning design studio’, Proceedings of Association for Computer-Aided Design in Architecture (ACADIA), Seebohm, T. and Van Wyk, S. (eds.), Quebec City, Canada, 22-25 October, 1998.![]()

7. Harrison, S. and Dourish, P. (1996). ‘Re-place-ing Space: the Roles of Place and Space in Collaborative Systems’, Proceedings of Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW’96), Boston, Massachusetts, 16 November 1996, Boston, Massachusetts: ACM Press, pp. 67-76.![]()

8. Russell, B. (1914), Our Knowledge of the External World as a Field for Scientific Method in Philosophy, Chicago: Open Court Publishing.![]()

9. A game ‘engine’ is the core software component of a computer or video game or other interactive application with real-time graphics. It provides such functionality as rendering for 2D or 3D graphics, collision detection, sound, scripting, animation, artificial intelligence, networking, and more.![]()

10. Several authors have commented on how many video game developers do not pay enough attention to character development, resulting in stilted characters or a failure to use rich characters to help with more meaningful game play. See, for example, Sheldon, L. (2004), Character Development and Storytelling for Games, Boston: Thompson Course Technologies; Chapter 3: Respecting Characters, pp. 37-59.![]()

11. Game developer Elan Lee, who sat in on one of our discussions about character development and game play, pointed out that ‘fiction’ is one of the best tools available to a game developer.![]()

12. Sugar Pie DeSanto is still alive and still to be interviewed for this project. This obviously could clarify some of the issues about how her personality should be portrayed.![]()

13. Various authors have catalogued the different genres or types of video games in different ways. For example, see Novak, J. (2004), Game Development Essentials: An Introduction, Boston: Thomson Delmar Learning; Chapter 3: Game Elements: what are the possibilities, pp. 85-103. Novak visited with us and helped us in our early discussions of which game genres we might choose in constructing the Seventh Street virtual world and game.![]()

14. One answer to this technical problem would be to make our game part of one of the existing virtual worlds on the Internet, such as Second Life, which include tools for players to create their own places and characters. We had extensive conversations with Second Life about possibly hosting our game on their site. But for a variety of reasons, including those discussed above, we decided instead to develop the game in Torque, while in parallel develop a Second Life version, which will provide a means to compare and contrast the possibilities of the two genres.![]()

15. This is an issue being confronted by developers of ‘serious games’, an increasingly popular form of game in which the player is presented with a series of choices about a real-world problem and the decisions made help educate the player about the issue. One such game is Peacemaker, which educates people about the complexities of the Middle East conflict by having the player make choices about what actions to take to promote peace and avoid war. See ‘Saving the World, One Video Game at a Time’, The New York Times, 23 July 2006, http://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/23/arts/23thom.html (15 August 2006).![]()

16. This approach was based in part on the modular approach to video game story construction outlined by video game writer Lee Sheldon, who came to the class to work with students on storytelling techniques, although the modular approach adopted for this project was a much simplified version of Sheldon’s model. See Sheldon, L. (2004), Character Development and Storytelling for Games, Boston: Thompson Course Technologies; Chapter 14: Modular Storytelling, pp. 295-321.![]()

17. For more on this tension between narrative and game play, see Jenkins, H., ‘Game Design as Narrative Architecture’, First Person: New Media as Story, Performance, Game, Wardrip-Fruin, N. and Harrigan, P. (eds.), Cambridge, Massachussets: MIT Press, 2004. Also at http://web.mit.edu/cms/People/henry3/games&narrative.html (15 August 2006).![]()

© 3DVisA, Yehuda E. Kalay and Paul Grabowicz, 2006.