The Kashmir Question

by Jennifer Kho,

Mike McPhate, and Melis Senerdem

Ever since Pakistan and India shrugged off the reins of British rule in

1947 the two nations have fought bitterly. At the heart of the tension

is the disputed ownership of Kashmir, a Himalayan state of rugged beauty

caught between the rival nations. While Pakistan makes a pan-Islamic claim

to the state, which is populated mostly by Muslims, India argues its claim

as a matter territorial integrity. After 2 wars, 35,000 deaths and the

recent addition of nuclear weapons to both sides military arsenals the

path to peace more elusive than ever. Indeed, the current buildup of troops

along is the largest since the conflict’s beginning.

|

| A Pakistani soldier monitors Indian troop movements across Kashmir's Line of Control. |

Five top minds on the nature of the dispute spoke at UC Berkeley’s

annual South Asian Conference in February. Here are some brief excerpts:

Pradeep Chhibber, UC Berkeley professor of political science,

argued that at the heart of the conflict is nationalistic anxiety among

leaders in both India and Pakistan.

"The single largest source of tension between the two is the fear

that territory is somehow going to be taken away and things like religion

and ethnicity merely fall as categories that could be used to mask this

essential territorial division…If the tension between the two nation

states was either of religion or ethnicity then, I think the conversation

would have revolved around trying to understand who the Kashmiris are,

what Islam is. But that’s not the issue."

"When we think of the strategic balance in South Asia we have to

understand that tension exists because both nation states, even now, for

reasons good and bad understand their security in largely territorial

terms. And until they stop thinking in territorial terms, I think we are

in for the long haul."

Ahmed Khaled, a journalist with Pakistan’s The Friday

Times, discussed the role of Islamic intolerance in Pakistan.

|

| A replica of a missile built by a patriotic religious group is aimed towards India in Muzafferabad in Pakistan-controlled Kashmir. |

"People have started saying in Pakistan that Pakistan is being Talibanized.

But if you talk to somebody like Karzai, the new chief in Kabul, he will

say, ‘This Islam we have overturned. It came from Pakistan.’

And I think it’s partly true because all these people were trained,

the Taliban were trained, even Mullah Omar himself, were trained in the

Pakistani seminaries and all these high church ideas went from Pakistan

into Afghanistan.

And the moment the Taliban government were removed they also removed some

of the draconian laws that these people had imposed."

"I think it’s is going to be very difficult for Pakistan to

turn back this tide [of Islamic extremism] because its integral to the

concept of an Islamic state and I think wherever Muslims live on this

globe this is a problem for them. They have no idea how to reinterpret

some of the laws to treat the non-Muslims minorities and they have no

idea how to reinterpret regional law and treat their women well."

Sumit Ganguly, professor of Asian studies and government at the

University of Texas-Austin, argued that no party to the conflict is representing

the wishes of the Kashmiris

"Today the [Kashmiri] insurgency is a far cry from its original

self in 1989. It no longer represents the outburst of a people who finally

felt they could no longer tolerate the yoke of Indian rule. Today it is

mostly a protection racket."

|

| Family members of young Kashmiri Mohammed Shafique, 17, who was killed by Indian shelling. |

"There is ample evidence, this is not just a matter of conjecture,

that these insurgents no longer represent the pristine wishes of the Kashmiri

people. Rather, they represent no one but themselves. They are engaged

in murder, mayhem, rape and lots of other atrocities to boot and they

do not in any way represent the interests of the Kashmiris, however one

chooses to define those interests. These people would not be the liberators

of Kashmir by any definition and arguable would bring in an order much

worse than the one that exists in Kashmir which is repressive enough."

"Any settlement of the Kashmir dispute must include the two following

ingredients… Unless one addresses or makes a concerted effort to

genuinely address the underlying grievances of the Kashmiris, especially

in the valley, the aggrieved population, I’m afraid just like in

the bible ‘The poor ye shall always have with you’ similarly

the Kashmiri problem ye shall always have with you."

Ganguly also offered some terms for a solution.

"By the same token India is going to make little or no effort to address the underlying grievance of the Kashmiris unless there is a decline in support for terror in Kashmir. We cannot keep brushing this under the snow in Kashmir. We have to forthrightly face that the Lakshar-e-Taiba and the Jaish-e-Mohammed the Harkat-ul-Mujahideen and various other associated groups do not represent anyone but themselves and anyone who tells you otherwise is a fool or a naïve or both. I think both."

US Department official Neil Joeck discussed America's new relationship

with South Asian countries following 9-11.

"After September 11 significant changes occurred in some of our

policies. Initially, we were very appreciative of the very strong and

unstinting support shown by New Delhi for the US operation 'Enduring Freedom'

to respond to the attacks organized by al Qaeda against the World Trade

Centers and the pentagon, and to support us in our efforts in Afghanistan.

At the same time, as time went on, we strongly voiced our opposition and

concern about the terrorist attacks against India itself, specifically

on October 1st when the Srinigar state assembly was attacked and then

again on December 13th when the Indian parliament was attacked. That said,

we discouraged India and did not agree necessarily with India's approach

to seeking to resolve its problem with terrorism through conflict. The

US-Afghanistan problem we saw as quite different than the India-Pakistan

relationship and therefore have been engaged with India in seeking other

means to solve India's problem with terrorism than through conflict with

Pakistan."

|

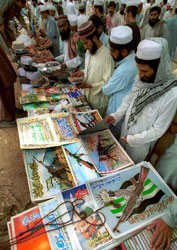

| Members of the Party of Islam purchase posters of guns outside the mosque after Friday prayer in Islamabad. |

"With respect to Pakistan, policy changed significantly. Again,

Pakistan, after a week's time, voiced full support for operation 'Enduring

Freedom'. The president of Pakistan eliminated his chief of the Inter-services

Intelligence Directorate. He changed his policy, did a 180-degree change

with respect to Pakistani support of the Taliban. We very much endorsed

president Musharraf's rejection of supporting terrorism regardless of

where it emanated from. He banned Jaish Mohammed, he banned Lakshar-e-Taiba,

arrested over 2000 of their adherents, froze their accounts and, in general,

took significant steps to change Pakistan's support for those organizations.

We also took particular note and appreciated the speech he gave on January

12th where he challenged the Islamic world as well as the people of Pakistan

to refocus jihad, not to let the idea of jihad within Islam be hijacked

by terrorists and murderers such as al Qaeda but rather to refocus jihad

toward fighting illiteracy, toward fighting poverty, toward social reformation.

At the same time, he said he would not support infiltration across the

line of control and we look forward to full implementation of that policy."

"Regarding Kashmir we are very concerned after the December 13 attack

of the buildup of forces between India and Pakistan. Again, I would stress

the importance of president Musharraf's speech of January 13th in support

of a peaceful resolution of this and an end infiltration across the line

of control. In that regard, we have seen some encouraging signs regarding

the diminishing of infiltration and the lessening of violence and we encourage,

as we have before, that both sides to engage in dialogue. The threat of

nuclear exchange connected with this is of particular concern and draws

our attention all the more."Columbia Professor Saeed Shafqat argued

that political and economic reform in Pakistan is underway. And though

religious radicalism will be hardest to tackle, he said there is reason

for optimism.

"Will Pakistan be able to bring about the kind of changes which

internally it has been asked to and externally it has being suggested

to? That's the kind of challenge that one is really confronted with.

"If one is looking at the religious part of it then one has to see to what degree they will be able to really manage this. As I see it, in all probability there will be considerable tension within the country on this. Nevertheless, in countries like Pakistan public protest somehow or the other does not really influence much as far as the policy process is concerned. But if the policy is able to convince the public that it is in a position to redirect itself, that it is in a position to consistently make a case for this then you will begin to see some changes taking place."