![]()

|

The

consequences of truth: Post-traumatic stress in new South Africa

(continued) Part 4 of 7 |

|||||

|

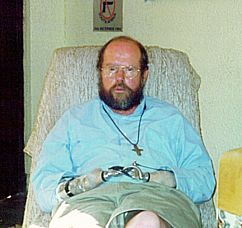

Healing Memories It was just weeks after Nelson Mandela was released from prison when Anglican priest Michael Lapsley opened his mail in his home in Zimbabwe on April 28, 1990. He was immediately blasted by a letter bomb hidden inside the pages of a religious magazine. The explosion took out the ceiling of three rooms of his house and ripped a huge hole in the floor. It was a bomb designed to kill. But Lapsley was sitting down when he opened it, and survived the blow, though his life would never be the same. Both his hands were blown off, one eye was permanently destroyed, and his eardrums were shattered. Today he lifts a glass of lemonade to his lips easily, takes a long drink and then sets the glass down on the carpeted floor of his modest home in a Cape Town suburb. A photograph of Fidel Castro hangs on his wall next to a door that is propped open to let a single beam of light enter the room. He crosses his hands and the shiny silver steel of the prosthetic claws makes a soft clicking sound. Lapsley was expelled by the National Party from South Africa in 1976. He was a white priest ministering to black students at the University of Natal at the time, and became increasingly vocal in his opposition to apartheid after the killing of black schoolchildren during the Soweto uprising. Though he knew he would always be a potential target of the apartheid regime, he says it wasn't simply his affiliation with the ANC that placed him at risk. "In my own view, in the end it was my theology which was a threat to the apartheid state, because my contention was that apartheid was a choice for death carried out in the name of the gospel of life, and therefore it was an issue of faith to oppose it," he says. In 1992, two years after he received the letter bomb that nearly killed him, Lapsley left Zimbabwe to return to live in South Africa. "It was a natural instinct to return and be part of a new phase of struggle, the phase of creating a different kind of society, and my particular contribution was to be a part of the healing of the country." In 1993 he co-founded the Trauma Center for Victims of Violence in Cape Town, where he initiated a series of three-day memory workshops. In August 1998 he broke off from the center and found the Institute for the Healing of Memories, which offers workshops to any South African who wants to tell his story. Exposing people to the humanity of others, he says, creates room for people to change. He estimates that 1,500 people have been served directly by the Institute. Small, grass-roots organizations like Lapsley's have been an integral part of the emotional clean-up process left by the legacy of apartheid, and in part, by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. "Whilst a limited number of people came before the commission," he says, "every South African has a story to tell about the apartheid years - the story of what we did, the story of what was done to us, the story of what we failed to do." Lapsley told his own story to a packed audience at a TRC hearing in Cape Town in 1996. “I remember pain of a scale that I didn't think a human being could ever experience,” he told the commission. “I remember going into darkness - being thrown backwards by the force of the bomb." He said he holds former President F. W. de Klerk responsible for his bombing , saying the bomb could not have been sent without his knowledge. He said he wanted an apology, wanted to hear about what the Nobel Peace Prize winner was doing for the healing of the nation. "I have not heard from de Klerk one word of remorse," he said, the anger in his voice clearly detectable. He pauses now, remembering his testimony. "The truth commission was like a giant mirror put in front of the country. Like never before in history, the past of a nation was center stage," he says. But the mirror revealed a country whose wounds have yet to heal, and it revealed the complicated process of reconciliation and forgiveness. |

|

||||