Finding

More Donors

After weeks of planning, mailings and phone calls,

18-year-old senior Beverly Dedini sits on the floor of her Bear Creek

High School classroom and listens. As part of her senior project, Dedini

organized Organ and Tissue Awareness Day at her school, bringing together

donation advocates and recipients. Because of her efforts, students across

the sprawling Stockton, CA, campus are learning about how they can donate

their organs and tissue - and perhaps save someone's life.

Dedini understands how donation can change people's

lives because it changed her own. Dedini's father, Michael, 44, had suffered

since childhood from holes in his heart that eventually destroyed his

lungs. But eight years ago, he successfully received a heart and double

lung transplant that saved his life.

|

|

photo Gina Comparini |

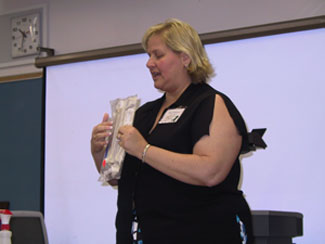

The awareness day that Dedini organized at Bear

Creek High is very much a hands-on event. In one room Mary Freeman, a

representative from the Northern California Transplant Bank, passes around

human bones in sealed packs. As the students press and examine the hard,

grayish bones, Freeman explains how parts of their bodies can be used

to help others. In a nearby room, a liver transplant

recipient tells another group of curious students how she was able to

attend college because a complete stranger died and gave her the gift

of life.

Organ and tissue donation is a chain with many

links. One person dies and gives an anatomical gift, another person receives

it, and the lives of family and friends on both sides change forever.

Community outreach and volunteerism are vital to the success of donor

organizations. Staff members at procurement organizations provide technical

information and other assistance, but volunteers bring the message and

mission to the public.

Some people volunteer for the outreach work because

they had made the decision to donate a loved one's organs or tissue after

they died. Others volunteer because they might have died had they not

received a donation. Then there are the many family members and friends

who volunteer because they would have lost a loved one if not for organ

donations.

Many people decide to become donors after hearing

volunteers speak, according to the California Transplant Donor Network.

"You really have to tap into your emotions,"

says Julie Moulet, one of the speakers at Dedini's awareness day event.

Moulet, who spoke with a framed photo of her daughter propped on one knee,

had donated her daughter's remains after she was killed in a car wreck

in 1992. Later that year, Moulet was diagnosed with liver failure. In

1997, she received a liver transplant from a 23-year-old man who died

in an accident.

|

|

photo Gina Comparini |

Mary Freeman, a donor development coordinator with

the Northern California Transplant Bank, says that during her presentations

she tells students to go home and tell their parents what they learned

about donation.

"Their parents might say, 'Well, that's not

very nice,' or 'Don't even talk about that!' But at least it gets them

talking," she says.

Judging from the pained looks on some of the students'

faces, learning about brain death and organ and tissue donation isn't

easy. One student cried during a discussion because it reminded her of

a recent death in her own family. There were some silly questions about

brain transplants but also some thoughtful ideas about why more people

don't choose to donate. Bear Creek student opinion varied widely. In one

classroom, a young boy said he wanted his body buried, end of story. Others

said they felt donation was the only sensible thing to do.

Drawing on personal experiences keeps the audiences

listening, and, at times, laughing. Cathy Olmo from the California Transplant

Donor Network talks about how her daughter received a liver transplant

when she was only two years old.

"She was dying before my eyes," Olmo

says. "Now she is a teenager and she drives me crazy. I mean, I have

to dye my hair now."

Later, in another classroom, Olmo implores the

students not to keep quiet about what they want their final act on earth

to be. She holds up donor cards with pink donor dots supplied by the Department

of Motor Vehicles.

"You can make a decision, but you also need to share it with your friends and relatives," Olmo says, holding up a white donor card. "Spread the word!"

©2003 Gina Comparini