|

|

Unsolved Murder Frustrates Police, Community One year after the murder of young Lisa Norrell, the investigation continues By Daniela Mohor and Ralph Gaston

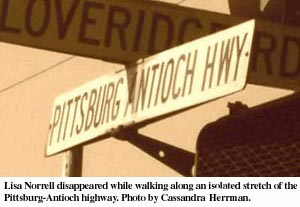

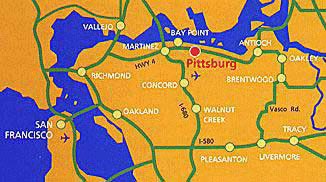

The office is the temporary home of Pittsburg's two-man homicide squad, and the unlikely epicenter of the official investigation into the slaying of Lisa Diane Norrell, a 15-year-old Mexican-American girl who disappeared from a party one night last autumn and never returned home. Her asphyxiated body was found, face down, her hands clenched in fists, a week later in the yard of a landscaping firm alongside the Pittsburg-Antioch highway on November 14, 1998. The slaying of the pretty and amiable Pittsburg high school sophomore shocked and agonized the working class town of 54,117 like few events in its history. But since that time, despite mass appeals for help and witnesses, there have been few leads and no charges brought in the case. And while the detectives who man the trailer office, John M. Conaty and Raymond Giacomelli, tirelessly continue to hunt for clues, reporting little on the record about their work, it's clear that nearly a year later no end is yet in sight. "The guys that are working on my daughter's case haven't stopped," said Minnie Norrell, Lisa's mother, who still weeps at the mention of her daughter's name and retains hope that the girl's killer will one day be brought to justice. "We talk all the time and they're working hard." Beyond the question of who committed the crime, the Norrell case has raised many other troubling and unsolved issues. Unlike other high profile murder cases of girls and young women in the Bay Area over the past year (see UNSOLVED), from San Francisco to Yosemite National Park, it remains painfully unsolved, and something of an open emotional wound in the northeastern Contra Costa County community. The slaying has inspired fears about whether a serial killer is on the loose, seen two suspects arrested by Pittsburg police only to be released a day later, and witnessed the peculiar circumstance of a local fire captain escaping serious criminal charges in exchange for giving evidence in the probe. It has also sparked a court fight over media access to public records, after police and prosecutors sealed nearly every document relating to the investigation in hopes of encouraging witnesses to come forward. In August, at the urging of Pittsburg police, Governor Gray Davis issued a reward of $60,000 for information leading to an arrest and conviction in the case. The Pittsburg City Council added $10,000 to it. But still, apparently no one has come forward with information, and the uncertainty and lack of resolution of the case continue to unsettle many. This story provides details and an update about the Norrell case, the first of a spate of four other killings, three of them still unsolved, in the Pittsburg area over a two-month period last year.

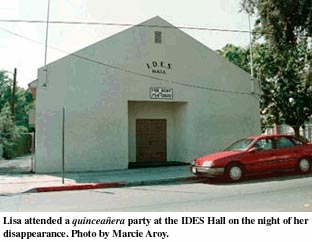

The quinceañera is a Mexican coming-of-age party, marking a 15-year-old girl's entry into society. It includes a lavish celebration with specific dances and formal attire, similar to a wedding. The night Lisa disappeared, she was practicing for the quinceañera party of a friend. According to participants at the rehearsal, Lisa angrily left the hall between 10:30 and 11 p.m. that night. Witnesses saw her walking on the Pittsburg-Antioch highway, presumably to get to her home on East 12th Street in Pittsburg. The highway is a lonely, poorly lit stretch of road. Lisa was wearing a long gray sweatshirt and blue jeans, and carrying the dark blue velvet dress and black dress shoes she had taken to the party. At 2:45 a.m. Minnie Norrell awoke from her sleep, and realized that her daughter had not come home. She and other members of her family spent hours looking for Lisa. It was a rainy and windy night, with temperatures only in the high 40s. "We got out, walked around in the rain looking everywhere. There was nothing anywhere," recalled Tony Quesada, Lisa's 17-year-old biological brother, who was adopted by one of Minnie's good friends. The circumstances in which Lisa left Antioch's IDES dancing hall that night remain unclear. All the community knows is that she left in anger. One of the Norrells’ neighbors, 75-year-old Julia Passmore, reported that Lisa left after "the dance partner she was supposed to practice with refused to dance with her." But Minnie's version of the facts is different: "I know my daughter; she probably got embarrassed because she couldn't learn the steps and then she did get mad." Minnie's only direct contact with the family that hosted the quinceañera was a few days after Lisa had disappeared. "[The father] said, 'I'm sorry that your daughter is missing,'" Minnie recalled. "'My wife thought she was with me, and I thought she was with my wife. I looked everywhere and couldn't find her.'" Many people don't understand why Lisa risked walking alone in the night.

"The funny thing is, I don't know what got her to be walking out

there," said City Councilman Frank R. Quesada, who is Tony's uncle.

"It's not a heavily used road, it's very dark and it's not a city

incorporated area." "Kids tend to do things that are crazy and risky without thinking about it. They have a sense of immunity," explained Christine M. Rohde, one of Lisa's high school teachers. "She was a very strong-willed young lady; sometimes that got in the way of her logic of things. And she was hurt," said Rhode. (See TEACHER) Lisa's family cannot help feeling some guilt for what happened. Minnie feels she might have missed Lisa's phone call, and Tony regrets not participating in the quinceañera party as his sister had wished. "I can see everything about that so clearly," said Tony. "At least if I would have gone, I know she'd be here right now." Although different families adopted Lisa and Tony, the siblings spent much time together and were very close.

According to the coroner's report, which the police heavily censored for investigative purposes, Lisa died of asphyxia (See RECORDS). Because of the censoring of certain details of the report, it is not clear whether she died of suffocation or strangulation. She had cuts and bruises on her chin and neck, and some blood and body fluids had been found on her sweatshirt. Police would not comment on whether Lisa had been sexually assaulted. Although Lisa's body was found on the side of the landscaping yard, between some parked cars and the building, none of the workers had noticed the body during the week she was missing. Police would not say if the body was hidden or buried in any way. During the week of Lisa's absence, Minnie relied on the support of her friends and family. "I had a lot of family here," said Minnie. "My family came and they just stayed. Their friends came and they stayed. The police came right away." Minnie also had to deal with a relentless media. "The press didn't let up, but at the same time, I needed them to have Lisa's name out there," she said. (See ETHICS)

Within two months of Lisa's murder, three more women were killed. All of the victims' bodies were discovered within miles of the industrial site where Lisa's corpse was found. Three of the victims were known prostitutes. Twenty-four-year-old Jessica Fredericks was found on Harbor Street in Pittsburg on December 5. She died of multiple cut and stab wounds. Rachael Cruise, 32, was found on California Avenue on December 15; she died of asphyxia and manual strangulation. The coroner's report on her death suggested that her body had been dragged along the road for a short period of time. Valerie Dawn Schultz, who was found on Willow Pass Road on January 8, died of multiple stab wounds. Evidence showed that she had also been strangled. She was almost 28 years old. Another victim, 38-year-old Tammie Davis, was found on December 15, severely beaten in a portable toilet in Bay Point, formerly called West Pittsburg. She is currently recovering from her injuries, although according to the officer in charge of her case, Detective Michael Costa of the Contra Costa County Sheriff’s Office, "she'll never be at full capacity again."

Though police had leads on Niaz as early as December, concern nonetheless rose in the community and spread through the media that the killings were all connected. Were women being targeted? Was there a serial killer on the loose? Deputies even went so far as to approach prostitutes in the area to warn them to stay off the streets. Police, searching for similarities with past cases, looked at the 1992 unsolved murders of two prostitutes in the Pittsburg area, Sharon Mattos and Andrea Ingersoll. Detective Costa said that he does not believe that any of the cases are related. "The fact that Davis was left alive makes me believe that these women were not attacked by the same person," said Costa. "We looked into that possibility, and I know that the Pittsburg police did too, but I don't see the cases being related." Pittsburg’s Inspector Conaty agrees. "There is no relationship between the cases," he said. On December 7, three tips about the Norrell case alerted the police to two Pittsburg men with a history of crime: David Michael Heneby, 25, and Garry Lee Walton, 39 (See SUBJECTS). After a short period of surveillance, police arrested the two on January 6, 1999 on suspicion for the murder of Lisa Norrell. Immediately after these arrests, a press conference was held in front of Police Headquarters, where police shared their theory on what had happened. The Contra Costa Times reported that Walton and Heneby, who allegedly did not know Lisa, were driving and stopped her a few hundred yards east of Nav-Land. Lisa was forced into Walton's car, which Heneby was driving, and killed a short time later after resisting their sexual attack, the paper said. "Sources near the case said that after Lisa was in the car, one or both of the men approached her sexually. After one of the men touched her, she insulted him, the sources said. He then became enraged and attacked the girl, they said." However, Walton and Heneby were released barely 24 hours after their arrests when Contra Costa County District Attorney Gary T. Yancey decided there was not enough evidence to bring charges against them (See TIMELINE). Heneby is currently serving a six-year sentence for domestic violence and assault charges. He is still believed to be a strong suspect, although police refuse to comment on the issue. The connection between Heneby and Walton has never been made clear, nor have the reasons that motivated police to arrest them. Soon after the release of Heneby and Walton, a new name appeared in connection with Lisa's case: Duanne Dee Shoemake. In September 1998, Shoemake, a former Antioch fire captain, had been charged with five counts of sexually molesting two young girls (See INFORMANT). But on January 11, 1999, even though a judge had declared there was ample evidence to put Shoemake on trial, the charges were dropped, reportedly in exchange for his giving evidence to police about the suspect, Heneby, who was his niece's husband at the time. Contra Costa County Deputy District Attorney Brian Haynes and Pittsburg police refused to disclose what, if any, information Shoemake provided. The mothers of the two girls Shoemake allegedly molested at first accepted the dropping of the criminal charges. One of them said she had hoped the dropping of the charges would result in an arrest and conviction in the Norrell murder, which had devastated and saddened their town. But after seven months had passed and no progress had been made in the Norrell case, the mothers decided to bring civil charges against Shoemake. That case is due to be heard next month in Contra Costa County Superior Court in Martinez. The confusion and shock felt by many in Pittsburg over Lisa's murder have been accompanied by a sense of puzzlement over the progress of the case, which has seen a widespread effort by police and prosecutors to clamp down on releasing most information about it (See RECORDS). Within days after Lisa's body was found last November, police requested that documents related to the case be sealed. Though attorneys representing both the Contra Costa Times and the San Francisco Chronicle protested the move, Contra Costa County Deputy District Attorney Douglas Pipes, with the assent of Judge John Minney, ordered the erasure of nine words on Lisa's certificate of death and of approximately 50 words on the coroner's report. "The reasons that we would seal documents are that we believe the material to be integral to the case being solved, and that the release of that information would greatly hinder our investigation," said Pittsburg Police Inspector Conaty. Again, after Walton and Heneby were released, Pittsburg police avoided divulging the information they had gathered on the probe. They sealed the arrest and search warrants served on the two men. In March, under pressure of the Contra Costa Times and the San Francisco Chronicle, Judge Joyce Cram of Contra Costa County Superior Court eventually ordered that only heavily redacted versions of the warrants be granted to the public.

Within hours of Lisa's disappearance, organizations and individuals showed their support to Lisa's family and the police investigation in ways small and large, their outreach reflecting the closeness many in the proudly multiethnic town feel for one another (See CITY). The Polly Klaas Foundation, which assists families of missing children, created a hotline to receive information on Lisa's abduction and printed flyers. The organization relayed all tips to the police. Local media outlets, including KMEL radio, held fundraisers to support Minnie Norrell and the police probe. In January 1999, Antioch High School's annual "Penny Harvest" raised $2,000 in Lisa's memory. The Key Club, the community service organization in charge of the benefit, decided to donate some of the money to Lisa's family. In the same month, a Mayor's Youth Task Force was created in response to the community's increased fear for children's safety. A few months later, the Task Force issued a report that proposed to penalize truant students and set a day-curfew. In addition to these measures, the city plans to promote activities involving young people in the city government.

A young girl who died before her time. A loving mother left without her only child. Two arrested suspects released for lack of evidence. A former fire captain whose criminal child molestation charges are peculiarly dropped in exchange for information about the murder. A series of slayings, mostly women, mostly unexplained. A town still begging to know what happened and why. These are the events that have left Pittsburg with no sense of resolution, and a heightened sense of insecurity. "It's not over for some kids; they're still living with the grief," said Rohde, Lisa's teacher at Pittsburg High, about the lasting effects of Lisa's murder, nearly a year later. "They feel unsafe because they don't know what happened," said Rohde.

|

The

wall inside a makeshift trailer office near the Contra Costa County

Superior courthouse in the East Bay city of Pittsburg details the twists

and turns of a probe into murder. Index cards denoting important dates,

times, and possible leads, along with several color photos of suspects

and other sheets of information, blanket the wall nearly from end to

end.

The

wall inside a makeshift trailer office near the Contra Costa County

Superior courthouse in the East Bay city of Pittsburg details the twists

and turns of a probe into murder. Index cards denoting important dates,

times, and possible leads, along with several color photos of suspects

and other sheets of information, blanket the wall nearly from end to

end.  Lisa

Diane Norrell, a 15-year-old Mexican-American girl, was the adopted

daughter and only child of Minnie Norrell, an Italian-American woman

living in Pittsburg (See

Lisa

Diane Norrell, a 15-year-old Mexican-American girl, was the adopted

daughter and only child of Minnie Norrell, an Italian-American woman

living in Pittsburg (See  The

morning after Lisa's disappearance, her black shoes were found on the

side of the Pittsburg-Antioch highway. Police began scouring the area

with infrared video cameras. One week later, on November 14, Lisa's

body was discovered at the Nav-Land landscaping site, which faces the

highway. The manager of the company still remembers hundreds of policemen

inspecting the area, sending the staff home once they found the body

and closing down three blocks for about three days.

The

morning after Lisa's disappearance, her black shoes were found on the

side of the Pittsburg-Antioch highway. Police began scouring the area

with infrared video cameras. One week later, on November 14, Lisa's

body was discovered at the Nav-Land landscaping site, which faces the

highway. The manager of the company still remembers hundreds of policemen

inspecting the area, sending the staff home once they found the body

and closing down three blocks for about three days.  Out

of the five crimes, only one suspect has been charged: Mohammed Niaz,

who was taken into custody last March and is currently on trial for

Fredericks' murder.

Out

of the five crimes, only one suspect has been charged: Mohammed Niaz,

who was taken into custody last March and is currently on trial for

Fredericks' murder.