By Mike McPhate (class of 2003)

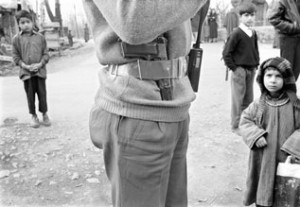

Soldiers patrol the streets of Srinagar. Approximately 400,000 Indian troops are based in Jammu and Kashmir. Photograph by Mimi Chakarova.

SOPORE, Kashmir, April 2003 – For the first time since the two nuclear neighbors snapped virtually all diplomatic links and squared off a year ago over Kashmir, there is the possibility of rapprochement between India and Pakistan. In an emotional address to his Parliament at the end of April, Indian Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee offered to open negotiations and said: “At least in my life, this is the last time I will be making an attempt to resolve the Indo-Pak dispute.”

That dispute is over Kashmir where a stepped up turf war between militants and moderates resumed with a bloody vengeance this spring. “The situation has assumed monstrous dimensions,” said Kashmiri leader Abdul Ghani Bhat, who belongs to the Hurriyat Conference, a mixed bag of 23 political parties, mostly moderate and all united in their demand for self-determination. “The two countries may have to go the Hiroshima way.”

It is just this possibility that alarmed diplomats and helped trigger the 79-year-old Vajpayee’s dramatic proposal that promises to bolster the position of the moderates in Kashmir — one that is much in need of reinforcing.

Moderates, mostly local Kashmiris, are eager to join a dialogue between India and Pakistan while the hardliners, supported by Pakistan, reject anything short of an outright merger with that country. Since 1947, when Pakistan broke away from mostly Hindu India and declared itself a homeland for Muslims, the two nations have wrestled bitterly over the ownership of Kashmir, and some 55,000 have died in the ongoing struggle.

India blames Pakistan for sponsoring the violence while Pakistan says it gives only “moral and diplomatic” support to what it calls a “freedom struggle.”

Yet Pakistan-based militants today comprise more than half of a total of 3,000 fighters in Kashmir, and while Bhat’s warning may seem to be a rhetorical flourish, the two nuclear powers came perilously close to nuclear war last summer.

Following a series of attacks in India, including one on Delhi’s Parliament building, which India blamed on Pakistan-sponsored terrorists, the rivals amassed a million troops along their border. The apocalyptic escalation was averted only after U.S. officials leaned on President General Pervez Musharraf to cut off the flow of fighters into India.

Washington’s pressure seemed to be working. For the first time, Musharraf declared that Pakistan would not “allow terrorism from its soil in the name of Kashmir.” But as U.S. attention has turned to hot spots in Afghanistan and now Iraq, the turf battle between militants and moderates in Kashmir heated up.

First on the militants’ list this spring was Abdul Majid Dar, one of India’s fiercest rebels who emerged unarmed from his forest lair three summers ago and said he wanted to talk with his enemies. “We will halt attacks against the (Indian) security forces. We want to show the world that we are not hardliners.”

But others within his ranks wanted to demonstrate otherwise. In late March, eyewitnesses said, intruders barged through the front door of Dar’s family home in Sopore, just north of the capital Srinagar, where he had stopped for a short visit, and fired “wherever they felt movement.” The bullets pierced his mother and sister and killed Dar as he sat waiting for lunch in his living room.

The children of Kashmir have been silent witnesses to the 14-year-old conflict and are psychologically affected the most. Photograph by Mimi Chakarova.

Most assume that the killers were from within Dar’s own ranks, the Hizbul Mujahideen, the militant wing of Pakistan’s radical Islamist party the Jamaat-e-Islami. His message of reconciliation, they calculated, had become too popular.

Only days after Dar’s murder, suspected militants followed up with the worst slaughter of civilians in Kashmir in three years. Pulled from their beds in the late evening, 24 Hindus in the farming village of Nadimarg — including two boys, aged 2 and 3 — were rounded up and gunned down in the town square.

Hafiz Saeed, the founder of Kashmir’s scariest militant group, Lashkar-e-Toiba, apparently justified the killing to journalists in Pakistan. “The solution is not to bow before India and beg for dialogue,” Saeed was quoted as saying in the Friday Times. “[The Indians] only understand the language of jihad. We have no choice but to respond by killing Hindus.”

Soon after, India began making a case for war.

“I genuinely believe that if possession of weapons of mass destruction, absence of democracy and export of terrorism are the criteria,” Indian Foreign Minister Yashwant Sinha said recently, drawing a comparison to the U.S. explanation for attacking Iraq, “then no country deserves more than Pakistan to be tackled.” Pakistan said it would give a “befitting response.”

Washington took note, with Colin Powell promptly denying any “similarity” between the situations in Iraq and Pakistan.

In his first move to change the climate, Vajpayee flew to Kashmir in early April, the first Indian prime minister to do so in more than a decade. He offered a “hand of friendship to Pakistan” and to all groups who “abjure the gun.”

The prime minister’s effort got a boost this month when the U.S. State Department added Hizbul Mujahideen, the group suspected of being responsible for the March murder of Dar, for the first time to its list of terrorist organizations.

Sumit Ganguly, author of “The Crisis in Kashmir” and a professor at the University of Texas-Austin, says today’s militants or jihadis are nothing more than crusaders and mercenaries that care little for the wishes of Kashmiris. “Anyone who tells you otherwise is a fool or a naive or both,” he said. “They are engaged in murder, mayhem, rape, and lots of other atrocities.”

Yasin Malik, chairman of the Jammu & Kashmir Liberation Front, speaks of the struggles in Kashmir and the uncertainty of the region's future. Photograph by Mimi Chakarova.

The Pakistani fighters are driven by a severe version of Islam. Their ideological training in the radical Deobandi and Wahabbi Islam is at odds with the softer, more tolerant Sufi faith of Kashmiris who have historically lived in peace with their Hindu and Sikh neighbors. “They (the jihadis) belong to a different Islamic heart,” admits Kashmir’s religious head and former Hurriyat chairman Mirwaiz Umer Farooq.

The most serious threat to the hardliners arrived last fall in state elections that delivered a new, moderate government to Kashmir. Independent observers said they were the first “free and fair” elections in over 15 years.

Kashmiris put their hope in the moderate People’s Democratic Party and its promises to bring a “healing touch” to the valley and to restrain the valley’s 125,000 Indian security forces, seen by most Kashmiris as a menace. Moreover, the party promised to make friends between separatists and Delhi.

Now, it remains to be seen whether these forces, with new help from Delhi and Washington, will prevail. At the end of his address to the Indian Parliament last week, Vajpayee, who is up for re-election next year, appeared determined to make the resolution of Kashmir his legacy. “I am confident I will succeed,” he said.