By Sonia Narang (class of 2008)

Sreeja, a Kerala bride, now arranges marriages between women from her hometown in south India and men in the north.

SORKHI VILLAGE, Haryana, December 2007—The day after her wedding ceremony, Omana and her new husband boarded the Mangala Express to make a 2,000-mile journey that gave her a panoramic sense of her changed life. The train left the verdant rice paddies and coconut groves of her home in southern Kerala and 56 hours later, she stepped off in the dry, brown fields of the north.

Up until that trip, Omana had lived with her parents and never left their village where local custom permitted her and other girls to wear their hair loose and to leave their face uncovered. Now, in her husband’s village in the northern state of Haryana, she is pronouncing words in a new language, learning to cook round flatbreads for her husband’s family, and adapting to the cold Haryana winter. Even the dress is different. Here, she must cover her entire face with a veil.

“It’s difficult doing my outdoor chores with this cloth on my face since I never had to wear this back home,” she said in broken Hindi as she sat in her husband’s home surrounded by his family. As she talked, she tucked loose strands of her hair under a scarf and showed a visitor the photos of her wedding.

Omana is part of a supply and demand phenomenon created by female feticide – the selective abortion of girl children, who many families here have long viewed as an economic burden. Up until ultrasound was introduced into India in 1979, many women were pressured to kill their infant daughters. Now, the new technology has led to selective abortion and some ten million female fetuses have been aborted in the past two decades, according to U.K.-based medical journal The Lancet.

Though sex selective abortion became illegal in India in 1994, the practice continues in many parts of the country. Female feticide is most acute in Haryana, a prosperous farming state where families can afford ultrasounds. The 2001 census counted only 850 women for every 1,000 men in Haryana. That imbalance has forced some in this country of more than a billion people to break with one of its more ingrained customs – marrying within one’s caste, a rigid class structure that defines a person’s place in society. Nearly 90 percent of the country’s marriages are within the same caste, but increasingly, Haryana’s eligible bachelors are looking beyond their region and their caste for brides. Even though doing so is considered the last step of a desperate man, it’s still better than staying single – for men and women.

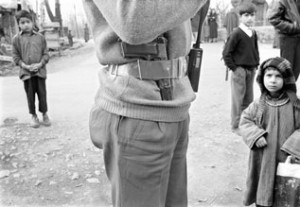

Three friends from Kerala, south India hold their children in a village in northern India, where there’s a shortage of brides.

The importing of brides or the “marriage squeeze” as a UN report called it, has created its own abuses – women trafficked from the poorest parts of India, women unable to produce children sold off to other men, and the importing of under-aged girls. Demographer Christophe Guilmoto, who authored the UN report, said that scarcity of women also increases the risk of gender-based violence.

While the Kerala women are treated better than the rest, women’s advocacy groups say it’s clear that the adjustments many make are dramatic. Kerala has one of the country’s highest literacy rates and Haryana one of its lowest. And the Kerala brides are also moving to a highly patriarchal society, where property is passed down through the sons and women move into their husbands’ homes. In Kerala, women wield power and no one would think of getting rid of a female child.

But, getting married is as important for women in Kerala as it is for men in Haryana. So, the surplus of bachelors in Haryana gave Omana something she couldn’t find in Kerala – a husband. Like Omana, other Kerala women are considered undesirable by Kerala men for a variety of reasons: age, horoscopes difficult to match, and an inability to pay the required dowry. While Haryana men would ordinarily never marry anyone with these so-considered glitches, none matter if they marry outside their state. The grooms even pay for the wedding, a cost traditionally covered by the bride’s family.

And, brides from Kerala are particularly sought after.

“People here think Kerala girls are better than those from other parts of India because they are well educated,” said Rekha Lohan, a researcher in northern Haryana. Kerala also has the highest ratio of females to males in the country, with about 1,100 women for every 1,000 men.

In Kerala, when families of prospective grooms inquired about Omana’s horoscope and found it was one of the rare ones known as unfavorable for marriage, they looked elsewhere. Every year, her prospects got dimmer. At 29, she was considered far past the marriageable age, and her family considered the options. They had heard of other local women marrying men from Haryana and so they sent Omana’s photo to one recent bride and it went from there to the house of Ajay Singh, a 34-year-old sweet shop employee. Before long, the couple met in Kerala for the first time and just days later married.

“These women don’t share anything with the men they marry,” said Ravinder Kaur, a sociology professor at the Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi. “They don’t share the language, they don’t share food habits or culture. Everything is very different.”

As a result, she added, the marriages are difficult in the first years. “But over a period of time, the women get accepted, they adjust, they learn the language and many of them who came a while ago dress and talk like the Haryana women,” she said.

The marriages are perhaps toughest in the smaller villages where the cultural practices such as wearing the head covering are strict. But even here, in the village, a few Kerala women are making their mark.

All the villagers, for example, know Sreeja, a 31-year-old woman from Kerala, who arranged Omana’s wedding and several other matches. After Sreeja’s matchmaking side business took off, she became the talk of the village and appeared on local newscasts. Though she works in the fields and dons the traditional head covering like most women here, she wasn’t willing to abide by the prejudice towards newborn girls.

Negative attitudes towards girls remain strong. “Haryana’s society doesn’t recognize they have created this shortage of women by eliminating their own girl children,” Kaur said.

Moreover, she added, as long as men are able to marry women from elsewhere, “They can pretend there is no crisis.”

Sreeja is an anomaly in the village. But nearby in the town of Hansi – just 10 miles away – strong Kerala women are becoming increasingly common. At present, the town of 75,000 people has about 300 Kerala brides, the majority who come from the same town in northern Kerala. Some of those marriages have been brokered by Usha and her sister Vasantha, who first married Haryana men several years ago. Now, with the help of their mother in Kerala, the sisters have enlarged their own community by arranging eight other matches.

“Earlier, I was always homesick and wanted to go to Kerala often,” said Usha, who lives with her large extended family in a two-story home with an open-air courtyard. Five years into her marriage, she comfortably moves about the house, cooks north Indian meals with ease, and speaks fluent Hindi.

“I was thinking about my mother, brothers, and sisters all the time.” Now, she doesn’t miss home as much and only visits Kerala for weddings or other major events.

She said her husband’s family welcomed her into their home, supported her, and even taught her how to cook like a Haryana girl. “The curries here are made very differently. We use coconut oil back home in Kerala and they use a different kind of oil here. I learned how to make the curries from my mother-in-law.”

Still, Usha feels most relaxed around other transplants from Kerala. On one recent winter day, she wrapped a chiffon pink scarf around her neck, put on a red sweater, and headed to a nearby house to meet her closest friend, who like most of her friends is also from her hometown in Kerala. These women are like her sisters, she said.

“If there’s some event in my home, I invite them. Similarly, they invite me over to their houses. If I fall ill and have to go to the hospital, they come with me to the hospital.”

As Usha navigated the narrow alleyways, she got a few stares, but mostly blended in with the others on the street. The minute she arrived at her friend’s home, she switched into her native language of Malayalam and the two women chatted over cups of steaming sweet tea.

When the women visit their parents in the south, the differences between life in Haryana and Kerala are immediately visible. As the train pulled into a Kerala village one January morning, the villagers were in the final hours of an all-night temple festival, complete with drumming, fireworks, and intense traditional dances performed by men in bright red masks and headdresses. In Haryana, the Kerala brides said, everyone would have been asleep hours earlier. And like New Yorkers who winter in Florida, Kerala brides prefer the warm weather of home to the cold weather of Haryana.

Usha’s mother Kalyani, who still lives in Kerala, said that marriage will always trump geography.

“When the girl gets old and is unable to find a groom and get married here, we’re fine even if she gets married to someone far away,” Kalyani said. Moreover, she added, even if her daughter and the other brides can’t stay in Kerala, they get married in the Kerala style.

“The groom’s family brings the wedding dress and jewelry to the bride’s house the day before the marriage.” Even though the brides permanently move to Haryana, Kalyani has no regrets.

“When I arrange a wedding, I’m giving the bride a new life and god will give me blessings,” she said.