By Jessi Hempel (class of 2003)

Pinkey watches as her mother spins cashmere. Photograph by Mimi Chakarova.

SRINAGAR, Kashmir, April 2003 – Pinkey Ahmed Dar has had just 14 birthdays so far and she has seen her father die, three brothers killed and a fourth go missing. She sits in her drafty two-room shack at the top of a steep staircase in a poor Srinagar neighborhood, and pulls her knees up under her pink woolen cloak. “I am scared,” she says. “Things scratch at the walls in the night.”

The fear that haunts her every night dates back five years to when Kashmiri police shot her third brother, Mushtaq, and brought his body to her house. “We didn’t know what had happened. The women were sitting around gossiping. Then they brought his body in,” she said, a white headscarf framing her large dark eyes. “I could see he’d been shot in the left eye — there was no eye.”

A few months earlier, her brother Mushtaq had joined a militant group fighting to cede Indian Kashmir to Pakistan. The police killed him a couple of hundred yards away in a neighbor’s backyard, according to several of Pinkey’s family members.

Pinkey was born in 1989, the year militants took up arms to fight over Kashmir, a state sandwiched between India and Pakistan and whose ownership both lay claim to. Until then, blood hadn’t stained the yellow fields of mustard and blossoming apple orchards that fill the Kashmir Valley. Pinkey’s mother Syeda remembers her own adolescence. “In the summers, we played outdoors at night,” she says.

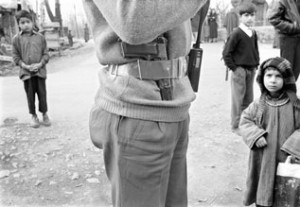

But Pinkey has passed through childhood in an era of violence and is coming of age at a time when it’s only getting worse. And there are countless civilians like her. Among the nine million people who live in Indian Kashmir, nearly everyone can name a close friend or relative who has been killed. They die after joining the militancy. They die after being taken into custody by the police. They die in crossfire.

A 33-year-old journalist from a village in the Valley mentions how he looks at his nursery school class picture and has, with a pen, marked out those who have been killed — almost 70 percent of the class.

“We have no men to protect us,” said Pinkey. And she’s right. While it’s the men who do most of the fighting and dying — 55,000 at last count — it’s girls such as Pinkey and mothers such as Syeda who are left to grapple with the grief and despair.

Pinkey sits next to her mother while she spins cashmere. She hasn't been able to work for a few weeks due to a lung infection. Photograph by Mimi Chakarova.

“Women have been the worst victims,” said Mehbooba Mufti, president of the People’s Democratic Party which was elected last year to head the state government promising to bring a “healing touch” to the scarred Valley. “It’s the women who go to the hospitals and to the police searching for their husbands and brothers. And then it’s the women who must carry the family responsibility.”

Mufti’s concern is as personal as it is political. In 1989 — two years after a rigged election left little room for legitimate political opposition in the state — her sister, who was then a medical student, was kidnapped. As ransom, the abductors demanded the release of some militants. Within days, the panic-stricken government in New Delhi gave in, released the militants and Mufti’s sister was let off unharmed. That kidnapping is widely seen as marking the start of the militant movement in Kashmir.

Since then, the cycle of violence has been non-stop. Although heavy winter snows bring some calm, freezing the mountain passes and making it more difficult for armed militants to sneak in from across the border in Pakistan, as soon as the trees show buds, the killing resumes.

Less than a week after the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in March, armed gunmen slaughtered more than half the residents of a Hindu village in the predominantly Muslim countryside. This came a day after the assassination of Majid Dar (not related to Pinkey Dar), a militant who was killed by members of his own group for advocating talks with Delhi. And later the same week, pro-Pakistan militants cut off the noses of six villagers suspected of spying for the Indian government.

Pinkey has trouble speaking of her brothers' deaths. Photograph by Mimi Chakarova.

Such violence leads to generations of women who live in a perpetual state of grieving. A visit to Pinkey’s home offers a glimpse into what that means.

Her mother, Syeda, is a frail woman with lung disease. She has callused fingers from her work spinning fabric into the Pashmina yarn used for shawls that retail in the United States for $200 apiece. She works 15 days to weave a skein of yarn the size of her index finger, which she sells for the equivalent of $3.

Her husband, a vegetable seller, died of natural causes shortly after Pinkey was born, leaving Syeda with seven children — four sons and three daughters. “I still had hope because of my sons,” she said. Her sons promised to build her a larger house, but then came 1989 and, for many young Kashmiri men, building the movement became the priority.

Syeda pulls a strip of three photographs from the window ledge, in which three young boys smile. Her first son, Nazir Ahmed Dar, is center strip, his eyes piercing and dark. At 25, he was recently engaged and selling vegetables in front of their house when militants lobbed a grenade at Indian security forces. Nazir was killed in the grenade attack.

The second son, Tariq Ahmed Dar, 18, was killed in crossfire. This time, it was the police who were firing on militants along the banks of a nearby river. A bullet knocked Tariq into the river’s current where he was swept away. His body washed up two days later.

Their 20-year-old brother Mushtaq, Syeda explained in the calculus of war, “became a militant because what else could he do?” Syeda isn’t clear how long he was on the run but one thing she knows: He outlived the average militant’s lifespan, six months, before he was killed.

Her fourth son, Nizar Ahmed Dar, was given a government job as part of the Indian government’s compensation for the family’s loss, but he was felled by mental illness. Syeda said she tried to take him to the psychiatric hospital but they couldn’t treat him. He would wander off into the night and turn up in odd places. More than two years ago, she said, he wandered off and never came back.

“I don’t care what happens in Kashmir. Whoever will come to our rescue can’t save us from this hell,” Syeda said as she looked down at the crumpled photographs of her first three sons. “All of them have perished, and there is no difference now.”

Across the city at the Valley’s only psychiatric hospital, Dr. Mushtaq Margoob works in an office atop the remains of the former inpatient facility. Mounds of dirt are littered with empty pill packages. The shell of the hospital sits in the shadow of the tomb of a Mughal emperor. Militants razed the hospital, like many, in the early 1990s to prevent Indian security forces from establishing a base there. Now Margoob dispenses treatment and medicine to a growing number of patients from a newer, makeshift building behind the rubble.

A young woman grieves over the death of her family which was massacred by unidentified gunmen in the village of Nadimarg. Photograph by Mimi Chakarova.

His patients complain of depression, insomnia, heart palpitations, and other signs of a fast growing problem for Kashmiris: post traumatic stress disorder. As the conflict continues, Margoob said that communities’ resources to support those who grieve have become depleted. “A Kashmiri woman in the past year has seen difficult things. A decade ago, deaths in communities were a collective shared trauma. People would visit their neighbors and offer support. But when this continued, everyone exhausted their emotional resources. Too many people have died.”

On a blustery Saturday afternoon, Pinkey visited her neighborhood faith-healer. “Nowadays most people who come ask me to pray for their protection against violence,” he said. “I give them an amulet with a black thread — a talisman.” He stopped to rearrange the coals in a small bucket by his feet. “What do you have to tell a person who has lost a husband,” a young woman asked him.

“You’re young, get remarried,” he said, with barely a pause.

“What do you have to tell a person who has lost her children?”

“You’re young,” he said. “Have more children.”

In 2007 Siddharth Varadarajan was a Nirupama Chatterjee Teaching Fellow at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism.

In 2007 Siddharth Varadarajan was a Nirupama Chatterjee Teaching Fellow at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism.